Notes and Queries Relevant to

“A Brief Assessment of the Ravished Armenia Marquee Poster” by Amber Karlins; published as a Research Note in the Journal of the Society for Armenian Studies

19:1 (2010), pgs. 137-145: Filling in Some Gaps and a Call for Information

Armenian News Network / GroongDecember 20, 2010

Special to Groong by Eugene L. Taylor and Abraham D. Krikorian

LONG ISLAND, NEW YORK

Abstract

Information on an advertisement for the screening of the film “Ravished Armenia” published as a full page black and white pictorial in The Saturday Evening Post January 18, 1919 confirms that the artist Dan Smith created the dramatic imagery of a brutish man brandishing a sword, gripping a struggling girl, and that he used as a model a work by the French sculptor and artist Emmanuel Fremiet of a gorilla carrying off a female. Dan Smith clearly states on this work “AFTER E. Fremiet.” Some recent reproductions of a color movie poster showcasing “Ravished Armenia” are not as easy to read, perhaps because of the color and size of reproduction constraints. Our research presented here supplements and broadens Amber Karlins’ “A Brief Assessment of the Ravished Armenia Marquee Poster” and at the same time raises a number of unanswered questions. Film historian and movie expert Anthony Slide has done much to expand our data base on “Ravished Armenia.” Even so, some matters of special interest to us have not been covered by him in very much detail. We have wondered who ‘really’ wrote the screenplay, or even whether there may have been two ‘screenplays’ or ‘scenarios’ written for the movie. The ‘original’ scenario credits Nora Waln, the publicity secretary of the American Committee for Armenian and Syrian Relief, and for a period, the editor of its News Bulletin. (She later became an acclaimed author.) Frederic (sometimes spelled with a ck) Chapin was shortly after credited as screenwriter. Were both involved in writing/polishing the screenplay “scenario? All indications are that Miss Waln’s version was the first, and that Chapin was given/took credit for some modifications, embellishments (?) and/or variations. (Perhaps buying the movie rights by Gates prompted the ‘takeover’ of the screenplay?) We suggest as a working hypothesis that there were two (perhaps only slightly varying) versions of the scenario. We hope that film enthusiasts and scholars will be able to keep this possibility in mind as they pursue matters relating to “Ravished Armenia.” In the interest of broadening awareness of recent literature relevant to the “Ravished Armenia” movie poster, we also draw attention to the publications of two experts concerning very different elements portrayed in, or conveyed by the poster (both in the context, and out of the context of the Armenian genocide). Attention is also drawn to a 2009 volume by Armen Khandjian that presents enormous amounts of information, profusely illustrated, relevant to Aurora Mardiganian and “Ravished Armenia.” In the course of our research we have acquired a fair amount of information on “Ravished Armenia” especially through access to the several printings ‘editions’ and even translations of the book. It was only considerably after our paying special attention to printed materials that we learned of the ‘newly discovered’ film fragment and the movie poster. In the course of our “Ravished Armenia” work, and in true serendipitous fashion, we came across an essentially overlooked photograph showing an early stage of the “deportation” process as it unfolded or progressed in Kharpert. Interestingly, only the initial softcover edition of the “Ravished Armenia” book uses the photograph as a frontispiece. Serendipity made our convoluted journey well worth while. We also ask at several points in this communication some questions which someone ‘out there’ might hopefully be able to address.

“Serendipity :- Serendip, a former name for Sri Lanka + ity.

A word coined by Horace Walpole, who says…that he had formed it upon the title of the fairy-tale ‘The Three Princes of Serendip’, the heroes of which ‘were always making discoveries, by accidents and sagacity, of things they were not in quest of’.

The faculty of making happy and unexpected discoveries by accident. Also, the fact or an instance of such a discovery. Formerly rare, this word and its derivatives have had wide currency in the 20th century.”

From the Oxford English Dictionary; also see Merton and Barber, 2004, The Travels and Adventures of Serendipity: a study in sociological semantics and the sociology of science).[1]

It is worth repeating that scholarship is a process, not an event. One of the key approaches to carrying out research is to cast as broad a net as possible – at least at the outset of one’s studies. In this way one frequently ends up following unanticipated leads that allow one to uncover important information.

When Rev. Dr. James L. Barton published his “Story of Near East Relief (1915-1930): an interpretation” in 1930, he knew better than most that there was such a massive amount of information to be dealt with and that he could but scratch the surface if the volume size was to be kept manageable.[2] Necessarily he gave a relatively broad sweep of the organization and its important activities. Even so, it is a densely written book packed with information. Today that volume is a lynchpin, the central cohesive element that enables one to gain a better understanding of how the United States of America in particular met the challenge of trying to ‘save’ Armenians (and Greeks and Assyrians of Asia Minor and “Bible Lands”) after the cataclysms of genocide and crimes against humanity were perpetrated under order of the Young Turk regime during World War I and thereafter.

When an appreciative notice of the Barton volume appeared in the New York Times Book Review Section pg. 18 in the December 14, 1930 Sunday Magazine, a striking and well-deserved accolade was given the work (incidentally its cost was $2.50). The reviewer wrote: “In a very real and intimate sense this book belongs to almost the whole of the people of the United States, since almost every man, woman and child in this country contributed to the Near East relief,[3] the story of whose labors and achievements it tells…Over half the book…is devoted to the story of what was done for the children, the 132,000 waifs and orphans, wreckage of the war, whom the Near East Relief salvaged, fed, clothed, educated and trained to self-support, usefulness and adjustment to the new conditions in their own countries….No one who gave anything whatever to the work can read it without a glow of pride that he, too, helped, in however small measure, in achieving such results.”[4]

Today, historical interest in the work of the Near East Relief (NER) and its predecessors in name, such as the American Committee for Armenian and Syrian Relief, the American Committee for Relief in the Near East (ACRNE) etc. remains sustained. This seems to be due to the fact that many of the descendants of Armenian genocide survivors often seek written confirmation of bits and pieces of stories heard of, or read in family ‘histories or ‘memoirs.’[5]

The Near East Relief work which was carried out in various places that had been subjected to massacre and destruction, and which were later visited (and indeed worked in) by various workers frequently figure more than passingly in some of this ‘survivor’ stories and accounts. Some of the missionaries and relief workers brought Armenian orphans back to America; some were formally adopted. (So far as we are aware, this is a subject that remains largely unexplored.)

The very wide range of Near East Relief materials, both archival and scattered in private collections, offers opportunities to uncover bits of information that vary considerably as to relevance to, and significance for ‘family histories.’ Whatever the case, such materials are always of interest to those trying to reconstruct the events of the period in question.

From our own perspective the Near East Relief materials (in the broadest sense possible of that organization’s name) have allowed us, over the years, to ferret out important images and photographs of the organization’s activities, and to learn specifics about the photographs that have frequently remained largely conjectural. So far, the story of Near East Relief has yet to be given a truly personal face, so to say, and this is one of the objectives of our ongoing work aimed at tracing and gleaning information from photographs of Near East Relief origin and from other sources, both related and unrelated.[6]

In what follows, we seek to place some of the “Ravished Armenia” materials such as the “Ravished Armenia” movie marquee poster in a more human-interest context, as well as to provide readers with some overlooked citations to the literature relevant to a better understanding of the poster. Last but not least, we wish to raise a few questions that readers might be able to answer. There is undoubtedly much information that is available in private hands. It is hoped that this communication will allow some additional insights or materials to emerge.

A Bit about the “Ravished Armenia” Poster

As is the case today, fund raising for relief was not then a trivial task and the problems to be solved and efforts that needed to be exerted were proverbially gigantean – humongous in today’s parlance. A wide combination of strategies and approaches were invoked for fund-raising purposes. Many personal appearances and talks were given by various knowledgeable people and ‘witnesses’ to the horrors. These included returning missionaries in particular. Some of them returned to work among the Armenians as relief workers after the war, especially beginning in 1919. After returning there were later atrocities that they reported on both in writing and in person. Some of the talks were illustrated (usually by means of stereopticon or ‘magic lantern’). A steady stream of pamphlets were issued as well as broadsides and artistically drawn and sympathy-eliciting fundraiser posters.[7]

“Ravished Armenia” was the first of a number of films of carrying length made or sponsored by the Committee(s). Regular and irregular news bulletins, magazines, and brochures of varying size were issued. In short, every conceivable approach was invoked.[8]

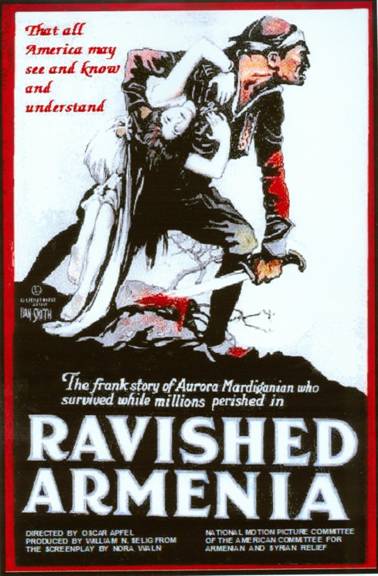

In her “Brief Assessment” of the movie marquee poster drawn for the film “Ravished Armenia” author Amber Karlins[9] provides from her perspective a context for, and details on a now fairly well-known poster. The poster shows the ‘Terrible’ or ‘Unspeakable Turk’ in a still-more terrible and unspeakable light. See Fig. 1. The poster image may also be seen on Internet on sites such as that of the University of Minnesota Center for Holocaust & Genocide Studies ‘Virtual Museum.’[10] Just how many original posters are still in existence is not known of course but there are at least a few.

Fig. 1

Enlarged from the front panel of a video case insert (see Fig. 3 below).

The first semi-official notice that the film “Ravished Armenia” was about to be released appeared in the News Bulletin of the American Committee for Armenian and Syrian Relief in its November 1918 issue (volume 2 no. 6). It reads:

“Ravished Armenia A Photo-Play

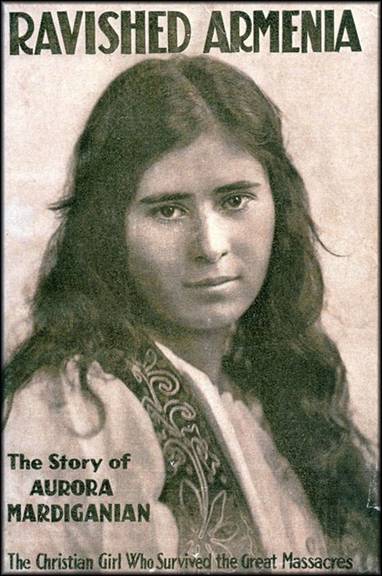

An eight reel photo-play will be released by the American Committee for Armenian and Syrian Relief in January entitled Ravished Armenia. This production tells the authentic story of Aurora Mardiganian which has been appearing serially in the Sunday supplement of several daily papers. [see Fig. 2 for a photograph of Miss Mardiganian which appeared in the September issue of the News Bulletin of the Committee for Armenian and Syrian Relief vol. 1 no. 16 1918.]

Aurora Mardiganian is an Armenian refugee aged eighteen who narrowly escaped massacre and made her way to America with help of the American Committee for Armenian and Syrian Relief. Historical facts of the Armenian persecutions gathered from the files of the State Department, Lord Bryce’s and Ambassador Morgenthau’s reports are also incorporated in the picture.

This photo-play is produced to enlist sympathy in behalf of all destitute survivors of the deportations and will be shown extensively throughout fifty cities during the campaign.”

Fig. 2

Miss Aurora Mardiganian in 1918, aged 17 or recently turned 18. (From News Bulletin of the American Committee for Armenian and Syrian Relief cited above; courtesy of University of Wisconsin Special Collections).

The “campaign” mentioned refers to the “Nation-wide Campaign for $30,000,000…January 12 – 19 [1919]” that was summarized as follows in the October issue of the News Bulletin…vol. 1 no. 17 1918.

“At a National Committee meeting held Thursday, October 17th [1918], William B. Millar, General Secretary of the Layman’s Missionary Movement, was elected general Campaign manager. A local campaign director was also appointed in each state of the union.

“Dr. Charles F. Aked will start November 3rd on an extended tour lecturing for Armenian and Syrian Relief and among other prominent speakers will present the cause all over the country during the campaign.

“Universal co-operation in this worthy cause has been enthusiastically guaranteed by the authors, publishers, cartoonists and advertisers as well as by churches and Sunday Schools all over the United States and Canada so that no stone will be left unturned to further the success of the drive.”

Ms. Karlins’ note on her study of the “Ravished Armenia” poster published in the Journal of the Society for Armenian Studies is based on an original in the Armenian Library and Museum (ALMA) in Watertown, Massachusetts donated by retired pharmacist Carl Zeytoonian. A copy of the poster is reproduced in her paper in black and white.[11]

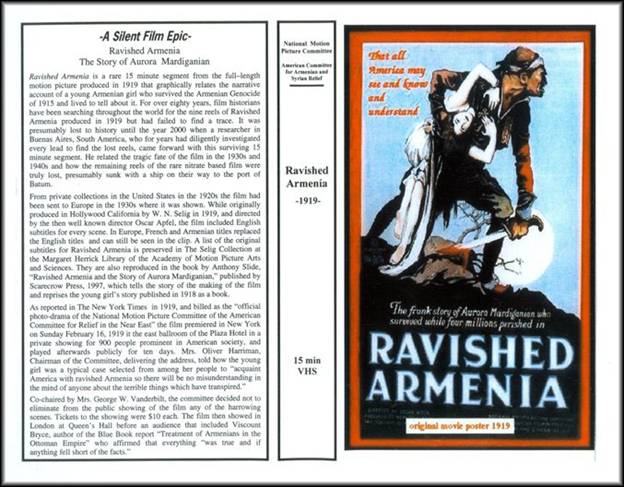

Some time back we bought by mail a VHS video tape copy of the re-discovered 15 minutes-long segment of the film “Ravished Armenia” from an Armenian-run bookstore in Los Angeles. The case had a color copy of the poster adorning it, along with a write-up stating a bit about the film . Notice was given on the back jacket of the remarkable sleuthing of Eduardo Kozanlian of Buenos Aires, Argentina and his role in retrieving it from some place or other in Armenia.[12] (See Fig. 3).

Fig. 3

Video jacket of an early ‘release’ of the film fragment of “Ravished Armenia.” Upon inquiry, the original source was not, or could not be disclosed, by the vendor.

After viewing the film, and being moved by the music of Samuel Barber’s Adagio for Strings, Op. 11, to which the fragment was set, we took note of several features and put the matter of the film on the ‘back burner.’ We did, however, take pains to make a DVD of the fragment from what we call ‘the Los Angeles (LA) VHS tape’ in the interest of preserving the video by yet another means, albeit without any attempt at restoration.[13]

Shortly before Richard Diran Kloian passed away he generously sent us a DVD of the ‘restored’, edited and captioned-in-English version DVD that he had worked on.[14]

This ‘restored’ film fragment has been shown relatively recently in various places nationwide, primarily to audiences with Armenian roots or connections, and has been not unexpectedly well-received.

No mention was made in Richard Kloian’s write-ups about the involvement of Eduardo Kozanlian in the discovery of the film fragment. To be more exact, nothing appears in the write-up that he provided us along with the DVD. There was an attractive new cover on the DVD case. Included with the DVD as an additional insert, was a copy in color of the “Ravished Armenia” poster showing the infamous ‘terrible’, ‘unspeakable Turk’ abducting a subdued or struggling a girl.[15]

The new-to-us image on the outside of the DVD case was, we believe, considerably less obtrusive and graphic than the ‘movie marquee poster cover’ we show reproduced above in Figs. 1 and 3. The ‘terrible Turk’ poster is also included as an extra in the inner jacket of the “Special April 24, 2009 Memorial Edition” given us by Richard Kloian. The new cover had apparently been retrieved from a Boston newspaper – to be more specific, as stated on the ALMA web site from the American Weekly Newspaper, Section of the Boston Sunday Advertiser Sunday January 12, 1919.[16]

There are, however, a few issues that persist in connection with Richard Kloian’s ‘restored’ and edited film. Some of the captions are less precise than one might like– for instance the date of the deportations from the Chimizgedzek[17] area in the Caza of Dersim north of Kharpert (Mamuret ul Aziz vilayet) did not occur in April 1915. According to Robert Kévorkian the deportation took place in early July (cf. pg. 517 of Kévorkian 2006) and this timeframe is in keeping with peripheral information available to us that we will not bother to present). Neither will we delve here into still other points. We regret very much that Richard did not live long enough for him to continue his work and for us to communicate with him on these matters. It would have helped resolve many outstanding questions, we are sure, for he was always ready to engage in lively conversation on such matters “The saddest words of tongue or pen, it might have been.”

To re-focus our attention on the Research Note by Ms. Karlins, we should emphasize that her paper presents following the trail of the imagery of the “Ravished Armenia” poster to a work crafted by the French master sculptor Emmanuel Fremiet (1824-1910). Indeed, the name Fremiet is clearly shown on the poster and we certainly concur with the conclusion, as Ms. Karlins has stated, that the artist Dan Smith used Fremiet’s sculpture as an inspiration or point of departure. As we shall see later in this communication, the advertisement image of the ‘poster’ published in the Saturday Evening Post unequivocally shows that Dan Smith wanted to credit Fremiet. There is no problem whatever seeing “After E. Fremiet.” Although the reproduction of the color movie poster shown in Fig. 1 may possibly have a bit about Fremiet, it is hardly visible – probably because the poster was not available to the VHS videotape ‘jacket maker’ in good enough detail to preserve that part of the poster’s labeling. Similarly, the reference to E. Fremiet is not to be found anywhere in Fig. 3. All this emphasizes that it is important to have good quality prints for serious study, even as one keeps in mind that there may have been more than one poster released, or that various bits and pieces of ‘doctoring’ of imagery may have taken place over the years subsequent to the actual use of the poster(s). (For example note that in Fig. 1 there is no moon shown on the picture whereas in Fig. 3 there is a moon.)

Ms. Karlins’ paper has a reference (her footnote 11 on pg. 140) to an article by Clive Marshall entitled “The Gorilla at Bay” published in “The San Francisco Chronicle” on January 12, 1919. The reference gives as its source Armen Khandjian’s “The Summer of 1915” pgs. 464- 467 (see our Endnote 5). While the title of the book is given, no name is given of compiler/author/editor who has unquestionably done yeoman’s work in assembling an enormous amount of interesting material on Aurora Mardiganian in the broadest sense of the name. In fact, Khandjian’s work has so much in it that it will take very careful examination to glean fully the rich store of information in it. (We shall return to that point below.)

We now turn our attention to some additional features associated with this movie marquee poster and Saturday Evening Post poster that can help give a considerably more personal face to them.

Two References to the Literature Relevant to the

“Ravished Armenia” Movie Poster

Regrettably, Ms. Karlins did not cite the seminal and detailed work of Marek Zgórniak entitled “Fremiet’s gorillas: why do they carry off women?” published in 2006 in a journal well-known and appreciated in the art world Artibus et Historiae (Kraków Poland).[18]

Zgórniak’s richly illustrated, and heavily referenced work is crucial to a full appreciation of the thematics connected with the “Ravished Armenia” poster. Emmanuel Fremiet was a contemporary of Auguste Rodin (1840-1917), the famous French sculptor. In France, Fremiet was reputedly a fine animalier[19] second only to the master Antoine-Louis Barye (1796-1875). (We believe that any serious museum goer will recognize some of their works even though they may not know the names of the artists. These artists are by no means obscure figures known only to art experts.)

Anyone who takes the trouble to read the article by Zgórniak will come away having a considerably enlightened perspective of Fremiet’s art and its consequences and legacy.

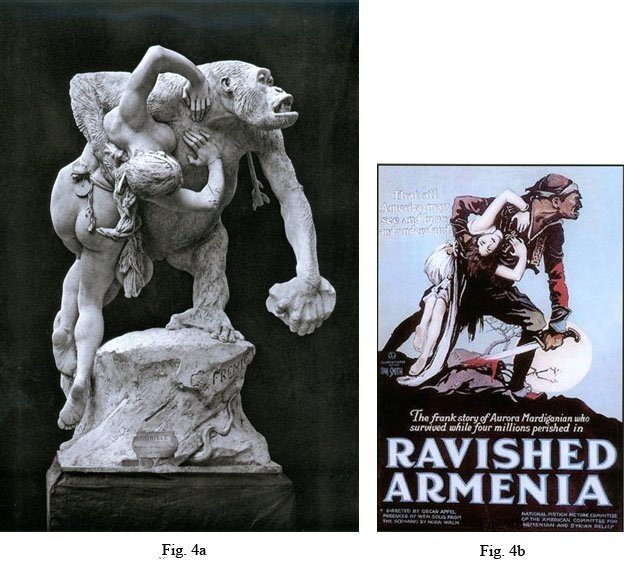

Zgórniak has provided the fascinating background and history to Fremiet’s Gorilla Carrying Off a Woman (Gorille enlevant une femme, Musée des Beaux-Artes, Nantes). It appeared in 1887 in the Paris Salon at which Fremiet won a first prize.[20]

Zgórniak describes how Fremiet’s several gorilla sculptures were not all well received by everyone. His critics fully exploited the sexual undertones of the works. Various and sundry sexual innuendos on gorillas (both real and imagined) and women were apparently rampant in various art circles at the time.

A citation in the Zgórniak article allowed us to seek out an early photographic reproduction of Fremiet’s gorilla. Fortunately Stony Brook University has the journal in which there is a full page Heliogravure by one Dujardin, printed by Chardon & Sormani. The Heliogravure technique was stated to be unexcelled in its ability to render blacks and greys, and we agree that it is excellent. A good quality scan of the “Gorille” is provided here for comparison (see Figs. 4a and b).

Fig. 4a Fremiet’s “Gorille” from L’ Art, Revue Bi-Mensuelle Illustrée volume 42 (1887) pg. 79; Fig. 4b, reproduction of a movie marquee poster entitled “Ravished Armenia” – perhaps more than one was released.[21]

A quote in Zgórniak, which was not his – see his pg. 219) sums it all up for us: – The gorilla is not only an ape, but also the personification of brute force; the figure of the beautiful woman and her desperate effort to defend herself are convincingly rendered.”

Yet another critical reference missing from Ms. Karlins’ note is an insightful article by Leshu Torchin entitled “Ravished Armenia: visual media, humanitarian advocacy, and the formation of witnessing publics” American Anthropologist 108, March 2006 pgs. 214-220.[22] Dr. Torchin states “Ravished Armenia is a significant case, not for its technical excellence – indeed, it received little more than tepid reviews and its success beyond the NER fundraising campaign is uncertain – but as an example of the convergence of international humanitarian activism and entertainment practices at the turn of the 20th century” (cf. Torchin 2006 pg. 214.)

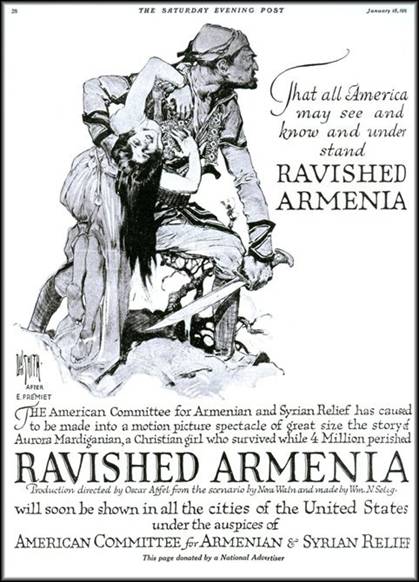

The Saturday Evening Post and the “Ravished Armenia” Poster

We cannot provide as fine a quality color image of an original poster as we should like, but can present here a black and white full-page picture of a considerably more informative ‘equivalent’ (in black and white – it seems not to have been colored) from an original issue of The Saturday Evening Post, January 18, 1919 pg. 28 (see Fig. 5). On the left-hand side of the page it clearly states “Dan Smith, and in block capitals AFTER E. FREMIET.” Certainly more details are available from that magazine advertisement than appear on the colored movie marquee poster. This will be apparent if one compares Figs.1 and 3 with Fig. 5).

We have not encountered to date the “Saturday Evening Post” poster in any other magazine. Armen Khandjian reproduces an image of the Fremiet gorilla in his exhaustive volume on “Ravished Armenia” (see his pg. 468; no source is given for the photograph.) Ms. Karlins credits “The Summer of 1915” but does not mention so far as we could discern authorship of the volume. Anyone planning to do any sort of additional research on the theme of “Ravished Armenia” certainly needs to consult Khandjian’s work. The difficulty has been that it is not yet widely known and is scarcely to be found even in the usual large research libraries. We came across it by a quite circuitous route. By bringing this volume to the attention of readers, we hope that we can help one save a lot of time and effort by first checking that exceptional resource. A remaining difficulty of Khandjian’s work however, is that many of the countless images/photographs printed in it have necessarily been reproduced from microfilm sources and therefore are not of the best quality. We have emphasized above that it is important to seek out if possible ‘original’ materials for careful examination.

Be all that as it may, it proves once again that various researchers can independently find the same materials and come to the same conclusions even though they follow slightly different paths. It is always useful to have ‘new’ but confirmatory information.

Below we will make a couple of guesses under the heading Nora Waln as to why the Saturday Evening Post carried the advertisement.

Query One: Has anyone encountered this black and white “Ravished Armenia” image in any other contemporary magazine? (Not newspapers.)

Dan Smith, Artist

More archival work deserves to be done on the life of the artist Dan Smith. He must have been familiar with the Fremiet work. Perhaps he saw it in Europe, or in some art magazine or journal. (There are, incidentally, works by Fremiet in the USA; see Zgórniak’s paper.) According to the obituary published in the New York Times December 12, 1934 pg. 23, Smith was born in Greenland of Danish parentage in 1865 (not born in New York City as stated by Ms. Karlins). This suggests that he was a mature artist when he executed the poster. It was more than likely a work donated for the sake of charity is as mentioned above in the notice of the $30,000,000 campaign. Smith and his wife gave their residence as 50 W. 67th Street, New York City when returning to the USA in August 1923 (fide Ellis Island in One Step database). See also pgs. 448 – 449 of The Illustrated Biographical Encyclopedia of Artists of the American West, Doubleday & Company 1976; pg. 291 of Historical Dictionary of War Journalism by Michael P. Roth, Greenwood Press Westport CT 1997, and pg.576 of Who was Who in American Art edited by Peter Hastings Falk, Sound View Press Madison CT 1985. From the available bio-data and especially from the hallmark ‘signature’ on the poster (see Fig. 5) there seems little doubt, as Ms. Karlins says, that Dan Smith was the creator of the “Ravished Armenia” poster.

Fig. 5

From The Saturday Evening Post vol. 191 (no.29) January 18, 1919 pg. 28.

Advertising and Publicity for the Film “Ravished Armenia”

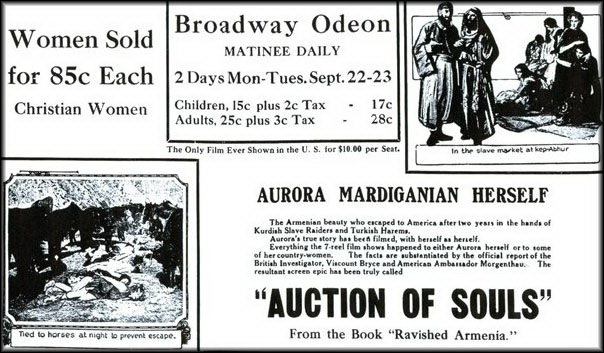

Access to a fair range of newspapers available online through Library of Congress’ in its Chronicling America newspaper archive suggests that the “Ravished Armenia” image in black and white printed full page at no cost to the Committee thanks to some “National Advertiser” in the Saturday Evening Post in 1919 did not appear in many papers either serializing or advertising the film. The vast majority of advertisements and articles encountered upon searching this site indicate an unspectacular (to us at least) advertising approach for the film. They usually are rather small ads and have no or little imagery. See Fig. 6 for one that does show some pictures.

Fig. 6

From The Evening Missourian (Columbia, MO) September 20, 1919 pg. 6. Courtesy of The Library of Congress’ “Chronicling America” online.

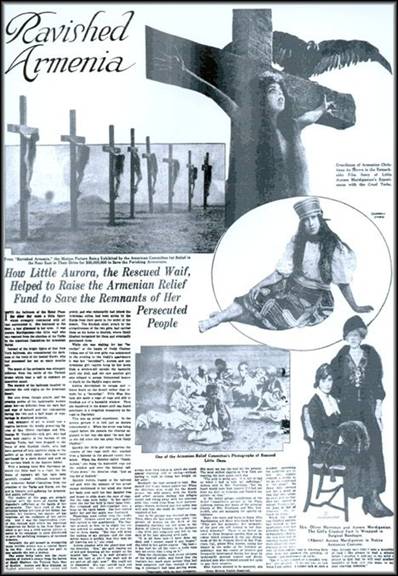

The notices for the film (or the book/s) that do have illustrations use images that are arguably only slightly less graphic than the colored “Ravished Armenia” movie marquee poster. How much less graphic is up to the viewer to decide, of course.[23] For example, there is one very disturbing example to which attention may be drawn that depicts nominal crucifixions of Armenian women and girls (Fig. 7) taken from the March 9, 1919 Washington Times (not today’s arch-conservative Washington Times but a newspaper started in 1902 and discontinued in 1939). This page shows stills from that film that are intended to ‘thrill’ the viewer. (A bit more on crucifixion is given below under our heading Concluding Commentary. Incidentally, the word thrill is used here in the sense of “moving with a sudden wave of emotion.)”[24]

Fig. 7

From The Washington [D.C.] Times 9 March 1919, National Edition,

The American Weekly Section [image 24] “Chronicling America” Library of Congress.

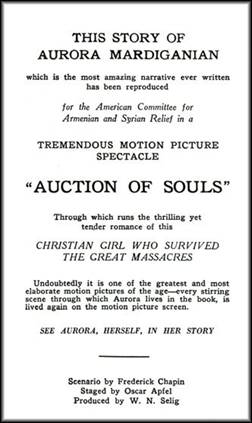

Nora Waln and “Ravished Armenia”

Ms. Karlins mentions Nora Waln, whose name appears among the credits on the movie marquee poster. She says, “Underneath the film’s title are the credits for the director, Oscar Apfel; the producer, William N. Selig; the screenwriter, Nora Waln; and the National Motion Picture Committee for Armenian and Syrian relief (Near East Relief).” Credits on some copies of the poster read “from the scenario by Nora Waln.”

Nora Waln, “author, journalist, speaker” etc. deserves at least a few more words here. In the foreword to the initial publication of the book “Ravished Armenia, The story of Aurora Mardiganian” etc. (see Fig. 8 for the title page) dated as written December 2, 1918, Miss Waln identifies herself as the ‘Publicity Secretary, American Committee for Armenian and Syrian Relief” – located at One Madison Avenue, New York City (cf. pg. 17).

Fig. 8

Title page of the initial American edition of Ravished Armenia released late 1918. Access to the copy from which this scan was made is courtesy of the Apkarian and Russell Archives.

When Nora Waln wrote her foreword, she was a young woman of 23 with what was to turn out to be a very interesting career ahead of her. She was born 4 June 1895 and died 27 September 1964. Mention is made in her obituary in The New York Times 28 September 1964 pg. 29 that she was “during World War I publicity director for the Near East Relief Committee in New York.” The biographical entry given her in Current Biography, Who’s News and Why (Annual, edited by Maxine Block) for 1940, pgs. 839-840 [which includes an attractive drawing of her head in profile] and which is by far the most detailed that we have yet encountered, states that she “entered Swarthmore College with the class of 1919 [i.e. in 1915] and left on our entry into the War to conduct a newspaper page in Washington called Woman’s Work in the War.”

This is not the place to go into Nora Waln’s many, especially later, accomplishments as an author. Her acclaimed literary works included a best seller on living in China, and another important and apparently much-read work that told of her life in Germany during Adolph Hitler’s nascent rise to power. Many of her books have been reprinted and are available for purchase on such Internet sites as Amazon.com. She had a daughter.[25]

Because originals of the initial edition of Ravished Armenia are not readily available, we present for easy reading, in full, a re-typed version of that foreword as an Appendix at the end of this paper.[26] This foreword certainly adds a more personal face to the “Ravished Armenia” scenario story.

Parenthetically, the foreword (re-typed) is also published in Anthony Slide’s work “Ravished Armenia…” on pgs. 27-31. It may again be found re-typed in the 1990 reprinting (not facsimile) by Fawcett; in that reprint – the foreword pages are unnumbered.

Archival materials at Swarthmore College and the Friends Historical Library (‘The Quaker Archives’) unfortunately do not have any Waln materials from her early period. They have a considerable amount of material on Nora Waln, but they mainly deal with her established literary works.[27]

An amusing anecdote about Nora Waln in connection with “Ravished Armenia” appeared in the New-York Tribune February 19, 1919 pg. 18. It reads: “Miss Nora Waln is a Philadelphia girl. Moreover, she is publicity secretary for the committee directing the $30,000,000 campaign for Armenian relief. After giving a newspaper reporter some information about the propaganda film play, “Ravished Armenia” (she wrote the scenario) a few days ago, Miss Waln said to the departing young man: “Thank thee for coming.” “Thou art some kidder,” returned the reporter, and would have said more had not H.F. Hancock who is handling the film’s publicity dragged him into the hall whispering, “Nix, nix; the lady’s a Quaker.”

We have not checked the City Directory records for Philadelphia in that period to see where in Philadelphia Miss Waln resided, but since The Saturday Evening Post was published in Philadelphia it seems probable that a connection existed that enabled the promotional poster for the film and the $30,000,000 drive to be carried free of cost to the Committee. This is consistent with the notice given earlier on in this communication describing the highly co-ordinated and co-operative campaign to raise $30,000,000. The Post apparently had a weekly circulation of more than a couple of million and was considered the most important general-interest magazine in America at that time. Nora Waln was certainly active in the promotion of the film “Ravished Armenia” and she is clearly credited as a Philadelphian with having written the scenario to the 8 reel film using information gained directly from Aurora Mardiganian (see e.g. Evening Public Ledger (Philadelphia) January 27, 1919 – Chronicling America, Library of Congress).

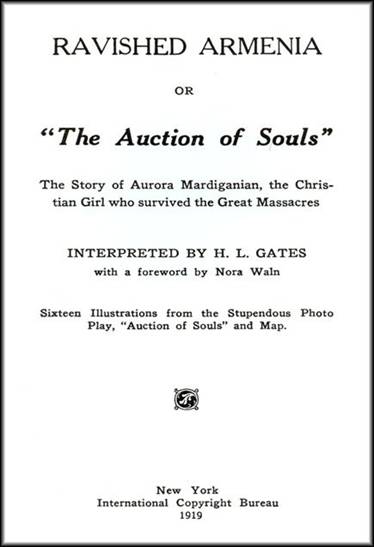

Access to a copy of the slightly later publication of “Ravished Armenia” gave us some additional insights, and opened yet another path for our studies. First of all, the ‘first’ 1918 edition states on its inside cover “Copyright 1918, by Kingfield Press, Inc. New York.” The next edition states on its inside cover, “Copyright, 1918” followed by “Copyright 1919, by International Copyright Bureau, New York.” Of considerable interest is that the illustrations reproduced in 1918 from photographs taken in historical Armenia showing various aspects of the “massacres” have been fully replaced in the 1919 edition’ with, and we quote ,“Sixteen Illustrations from the Stupendous Photo Play, “Auction of Souls” and Map.”[28] Compare Figs. 9, 10 and 11 to see the extent and evolution in credits.

Fig. 9

Access to the ‘first edition’ copy from which this scan was made

is courtesy of the Apkarian and Russell Archives.

Moreover, and perhaps significantly (and we say perhaps since we need a firm answer on this point) there is a page facing the Table of Contents that clearly states “Scenario by Frederick Chapin Staged by Oscar Apfel Produced by W. N. Selig” (see Fig. 10 below).

Fig.10

From this information alone we believe that it is not unreasonable to ask “Is it possible/probable that there were (at least somewhere along the line) two “scenarios?” Alternatively, one can ask whether Nora Waln “bowed out” or was “elbowed out ” or, was simply told that as part of the deal made to take over the rights her name was to be left out as well as any other indication that the Committee had any control any longer. Certainly by the time the British edition printed by Phoenix Press appeared in London (undated but perhaps late 1919/very early1920), Nora Waln’s name had disappeared and the word COPYRIGHT appeared beneath (albeit not directly) under H.L. Gates’ name (see Fig. 11).

Fig. 11

The English edition title page shown above further states Formerly Printed in America for Private Distribution Only as “Ravished Armenia.” But that statement presents yet another problem. The ‘second’ US edition printed in 1919 title page states “Ravished Armenia” or “Auction of Souls” etc. (See Fig. 12 for the title page to the 1919 US edition. Nora Waln is credited for her Foreword.)

Fig. 12

Query Two: Does anyone know anything more about two possible ‘screenplays’ for “Ravished Armenia”? Is it realistic to entertain a notion that there might be two re-discovered film fragments, one retrieved from some place or other in Armenia by Eduardo Kozanlian and another possibly by Richard Kloian? They might be somewhat different, or ordered differently and thus could be utilized to reconstruct a bit more of the film.[29]

Anthony Slide, an expert on “Ravished Armenia” states on pg. 8 of his book “Ravished Armenia and the Story of Aurora Mardiganian”[30] that “Nora Waln was credited in publicity materials for the film’s screenplay, but undoubtedly, Harvey Gates was heavily involved in the preparation of the script. The title through its shooting and initial presentation was Ravished Armenia, but at some point in 1919, the name was changed to Auction of Souls.” We will readily concede that the books may be viewed as publicity materials but vastly more people read the various printings than viewed the film(s). Presumably the word undoubtedly has been used by Mr. Slide after careful evaluation of the available information. As an aside, certainly Miss Waln was a budding writer and it is certainly not unknown that those who did the ‘real’ work – especially women in that day and age – ended up less with far less credit than they deserved.

The American Film Institute catalog says that “The film’s working titles were Ravished Armenia and Armenia Crucified. It may also have been known as An Armenian Crucifixion (see AFI Catalog of Feature Films, 1911-1920; F1.0146). The film opened originally in various cities at $10 a seat, the proceeds going to the Committee for Relief of the Near East and the Armenian War Relief Association. Sources disagree concerning the scenarist. Records from the Selig Collection credit Frederic Chopin (sic, read Chapin), while publicity pamphlets produced by the Armenian War Relief Association credit both Chopin [Chapin] and Nora Waln, a member of the committee. Shots representing Mt. Ararat were actually filmed at Mt. Baldy, CA.”[31]

In Anthony Slide’s book there is a copy of the title page of the first edition of the book (freshly re-set in type – not a photo reproduction of the page). It is simply entitled “Ravished Armenia.” The subsequent American printing states ‘Ravished Armenia” or “The Auction of Souls” (see Fig. 12).

The photograph facing the title page of the first edition ‘1918’ is not reproduced in Anthony Slide’s book. If it had been, we should have found ourselves, as the expression goes, ahead of the game long ago so far as the Kharpert deportation photograph now to be discussed is concerned.

Serendipitous ‘Discovery’ of a Photograph of

‘Deportation’ from Kharpert City

Mention has been made in an Endnote that a digitized copy of the Library of Congress’ holding (1st edition 1918) of “Ravished Armenia” may now be found on the Internet. We had never taken the trouble to track down a first edition, however we came across it by chance while visiting some friends.[32]

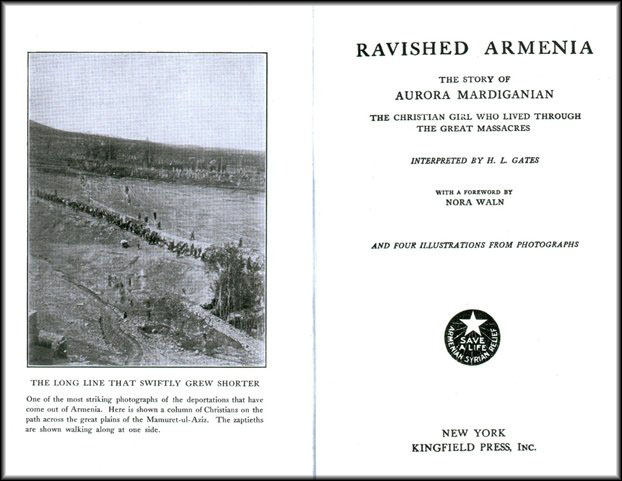

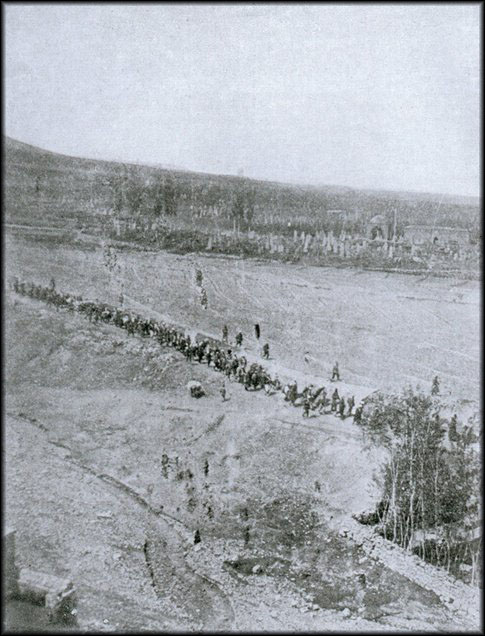

The frontispiece photograph in the ‘first’ 1918 soft-cover publication shows a “deportation.” The source of the photograph is not stated but more than likely it was in the possession of the American Committee for Armenian and Syrian Relief or its predecessor, the Armenian Atrocities Committee, or its successor, the American Committee for Relief in the Near East (ACRNE) – whatever. The caption reads:- “The Long Line that Swiftly Grew Shorter. One of the most striking photographs of the deportations that have come out of Armenia. Here is shown a column of Christians on the path across the plains of Mamuret-ul-Aziz. The zaptiehs are shown walking along at one side.” See Fig. 13.

Fig. 13

Title page and frontispiece photograph from the ‘1918’ (‘first’ edition of “Ravished Armenia”). Access to the copy from which this scan was made is courtesy of the Apkarian and Russell Archives.

We have no hesitation whatever in stating that the photograph indeed shows the slope leading from the small city of Kharpert (Harput, Harpoot) down to the plain in the vicinity of the provincial capital Mezreh, the lower-in-altitude and considerably smaller ‘twin’ city of Kharpert in the Vilayet (Province) of Mamuret ul Aziz.

There are few photographs of the deportations in the earliest stages of that terrible process and it would be good to have as good a quality photograph of this image for study and analysis. See Fig. 14 for an enlargement of this frontispiece photograph.

Fig. 14

Access to the copy from which this frontispiece scan was made is courtesy of the Apkarian and Russell Archives.

Query Three: Has anyone seen this important photograph anywhere else?

Concluding Commentary and Yet Another Query

It is to be hoped that additional fragments, even all of the movie “Ravished Armenia/Auction of Souls” will be found. Years ago, we embarked on a fruitless effort to track down the film after encountering what seemed an unlikely (and hence enticing) reference to “Ravished Armenia” made on pg. 545 in volume 2 of Richard Hovannisian’s The Republic of Armenia. From Versailles to London, 1919-1920. As it turned out no film was to be found among the British Archival materials referred to. Apparently there never was any film with the materials, i.e. it was not ‘lost.’ Undoubtedly, many individuals have sought to locate the film, following many leads. The quest should never end so far as we are concerned.

“Hope springs eternal in the human breast?”

Our intent throughout this communication has been to emphasize that any given trail followed with the purpose of elucidating one special point can lead to an unexpected find – however belatedly. And, significantly, a considerably broader picture and perspective can emerge simply by checking out a few leads. This is, of course, what research is all about. Serendipity certainly came into play more than once in our case. Armen Khandjian and Ms. Karlins can answer that same question, should they wish to, from their own perspective.

We never deliberately sought out a copy of the first edition of the book “Ravished Armenia.” This is because we thought we had access to one in the form of a paperback reprint put out in 1990 by Fawcett.[33]

For some reason, the photograph of the Kharpert deportation photo is missing from that reprint (perhaps the page was lacking in the copy they used to produce the reprint publication?) although the other photographs in the first edition are included. Assuming (and we have learned time and time again that one should never assume!) that reprint was a full and faithful copy of the 1918 edition, we noted the photographs, and let it go at that.

It seemed reasonable at that time to drop the matter until such time more important information surfaced. After all, we had a 1919 dated, hardcover copy with an additional bit of interesting information. It is perhaps worth stating at the outset that the copy with a stamped board cover had no dust jacket and we do not think it ever had one. There was an illustrated cover for the softbound/paperback (first) 1918 edition but it is very rare to encounter a copy with the pictorial cover nowadays. The few libraries that have the original volume apparently had the work hardbound for library use and it was not uncommon in those days to discard the paperback cover in the binding process. More is the pity for the first edition has an attractive and familiar image (in sepia color) of Aurora Mardiganian on it (see Fig. 15).

Fig. 15

Scan of a rare softbound/paperback edition of Ravished Armenia with Aurora Mardiganian on it. This is from the ‘1918’ first edition. Access to the copy from which this scan was made is courtesy of the Apkarian and Russell Archives.

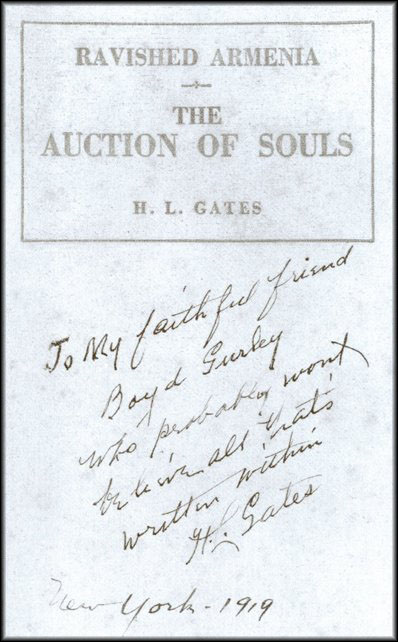

The second American release copy of the book “Ravished Armenia” (dated 1919) that we own is a presentation copy complete with handwritten inscription by H[enry]. L[eyford]. Gates (1880-1937) to Boyd Gurley (the editor of the Indianapolis Times, a progressive newspaper). It reads: “To my faithful friend Boyd Gurley who probably wont believe all that’s written within. H.L. Gates New York 1919” (see Fig. 16).

Fig. 16

Indeed!? The Film Institute catalog reads:- “Viscount Bryce’s official report and Ex-Ambassador Henry Morgenthau’s official story were additional sources for this film. The book was serialized in the Hearst publications. The film and the book are based on true incidents in the life of Aurora Mardiganian….” (for a bit more see also http://www.afi.com/members/catalog/AbbrView.aspx?s=&Movie=2105).

But having learned again and again that one needs to verify everything, especially in this kind of research, we believe that it should not be taken for granted that crucifixions occurred akin to those with which we are most familiar, namely that of Jesus Christ. There was more than a little discussion and attention given to the manner of crucifixion versus what is more accurately described as “impalement” in the aftermath of screening the “Ravished Armenia” film.

So far as we are aware, today there seems to be little serious questioning (this includes Ms. Karlins and Dr. Torchin) of the reliability of the perpetration of impalement [Crucifixion as usually perceived nowadays] of Armenian women and girls (and presumably of other victims of other ‘races’ of Turkish, Kurdish or Chechen etc. wrath) as covered, even exploited for particularly dramatic effect in the film “Ravished Armenia.” The fact is that the staging and portrayal of crucifixion in a film like “Ravished Armenia” depended on how the act (real or imagined) was perceived by the producers. Tortures of a wide and bewildering range including the routine use of the bastinado (falaka) to the point that the soles of the feet swelled in extremis and the skin broke due to edema, all the way to such sadistic acts as nailing horseshoes to men’s feet, tearing out beards, eyebrows and fingernails, gouging out of eyes, disembowelment and cutting of the unborn from their mother’s wombs were not solitary or rare occurrences. Accounts of these are accessible.[34] Various sorts of sexual abuse of women, and children of both sexes, and even men, was not uncommon.[35]

It is of considerable interest to note just how persistent the perceptions and conceptions of atrocities of a sexual nature that were committed long ago continue into the descriptions and relevant vocabulary of similar acts in much more recent and even modern times. The studies of Dr. Lynda Boose show that many atrocities committed in Bosnia by Serbs took on an aura and fell into a context much like that which existed in Ottoman Turkish times.[36] To render the whole ugly matter of sexual atrocities and their portrayal even more complex, Joel Schrock goes into considerable detail on rape in silent feature films, 1915-1927.[37]

Query: Can anyone help with specific references to impalements and the like during the Armenian genocide?

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank the staff of Stony Brook University Libraries for their ongoing and generous help. We again thank Pamela Apkarian-Russell and Chris Russell and the Apkarian and Russell Archives for having made their copy of the softcover first edition of “Ravished Armenia” available for scanning. We thank Vartan Matiossian for having communicated with us years ago on the involvement of Eduardo Kozanlian on his discovery of fragment of the ‘lost’ “Ravished Armenia” footage. We thank the University of Wisconsin Special Collections for allowing us access to their collection of their ‘New Near East’ materials. We are grateful to the archives staff at Swarthmore College for checking on the Waln materials. Last but not least, we thank John Gulbankian, Mary K. Rodgers and Dr. Daniel J. Tanner for reading the manuscript before submittal.

ENDNOTES