(© K. Vrtanesyan/Groong)

Armenian News Network / Groong

December 9, 2004

Travel Wire

By Ruth Bedevian

YEREVAN, ARMENIA

Antonina Pavilaitite was 21 years old in 1944 studying law in Vilnius University, Lithuania when the Soviet authorities arrested her and sent her to Siberia. It was there in exile that she met and married Gourgen Mahari, another victim who was exiled from Armenia to the GULAG twice in his life (1936-1947) and (1948-1954). Gourgen Mahari is still remembered in Armenia today by those old enough and by youth who have been taught by their parents and grandparents. He was a poet and novelist. `Had he written in English, Mahari would now be considered a precursor of Gertrude Stein and Hemingway.' So states Ara Balizoian (Hye Forum - October 30, 2002).

|

|

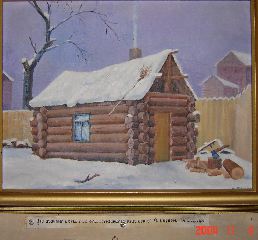

House in Siberia Painting (© K. Vrtanesyan/Groong) |

It was a sunny, clear, and unseasonably warm November day in Yerevan when my friend Karen and I arrived at Kassian Street, Building 3 and ascended the four flights of grey, worn steps leading to Apt 36 - Gourgen Mahari's apartment - where the door still is marked in distinct Armenian block letters with his name.

It was in this apartment where Gourgen resumed his writing career after being released upon Stalin's death (1953). Antonina, stood by his side, agreeing to live in Armenia with the man whom she loved and whom she encouraged to carry on despite the privations that his captivity forced him to endure. `When I met him, he was in such poor health. He was so ill. I had to give him courage. I said every day, `You must fight. Gourgen, you must live.''

|

|

Antonina Mahari (© K. Vrtanesyan/Groong) |

From the onset, there was no `ice to break' as this agile-minded octogenarian engaged me in a rapid sequence of questions in fluent English (which she learned in her native Lithuania and subsequently improved in Armenia). `Where do you live? Where were you born? Do you have children? Did you vote in the recent elections in the USA? Do you like Bush? Are you happy that he won? Where are you staying in Armenia? Did you come alone? How often do you come to Armenia?'

My desire to visit, I told her, was to express my respect and to carry messages of approbation on behalf of others as well for her late husband and his work, particularly his courageous honesty in writing The Burning Orchards, a novel that deals with the burning of the city of Van during 1915 including the climate of resistance prior and during the city's ruin and ultimate exodus. Gourgen, a 12-year old child, was witness to the siege of Van, ending up in an orphanage in Dilijan and eventually Yerevan. During the turmoil, he was separated from his mother and his sister committed suicide. His father had been murdered. Antonina said, `Eventually he found his mother who was living in Tiflis where she was working as a nurse.'

The original publication of The Burning Orchards, by Gourgen Mahari in 1966 was burned in public on the street in front of his home in Yerevan. The writer was the victim of a malicious campaign of abuse because it was perceived by those in powerful positions within the intellectual and political communities in Soviet Armenia and the Diaspora that his novel suggested that the behavior of Armenian revolutionaries antagonized the Turks, causing them to commit Genocide. So badly was Gourgen attacked and so weakened and hurt, he succumbed to the commanding pressure from the Writers Union and he re-worked the book. Antonina was steadfastly against this revision, believing in her husband's artistic integrity. As a result of all the stress, sadly, Gourgen Mahari died three years later, a physically broken and spiritually shattered man.

Presenting a copy of Marc Nichanian's Writers of Disaster to her, I continued to convey compliments to her from the author. I read aloud to her a quote from Christopher Atamian's book review (recently published in the Armenian Reporter, `Reading the Aghed: Nichanians's Writers of Disaster' - October 30, 2004 issue) in which Atamian explains that each character expresses a different viewpoint and discourse and he writes, `This made Mahari's subsequent persecution by his fellow Armenians, including fellow poet Paruyr Sevak, all the more absurd, as no one view could be held up to a mirror as having been Mahari's personal opinion of the events in question.' Also included in this documentation of expiation was Eddie Arnavoudian's commentary published as recently at July 14, 2004 on the Internet in Groong's Critical Corner in which he wrote, `The case against Mahari is artistically and politically as groundless as the campaign against him is beyond any moral, political or intellectual justification. ....The 1966 edition of 'The Burning Orchards' remains as one of the most accomplished of Soviet era Armenian novels. Its reconstruction of Van's historic Armenian social structure, its custom and tradition, its artistic, educational, intellectual and political world is brought to life through the varied relations of a host of defining and authentically universal characters.'

|

|

Mahari Wall of Photos (© K. Vrtanesyan/Groong) |

While Antonina and I were chatting, an official Russian document interested Karen. It was the application Gourgen Mahari had written to the Ministry of Interior asking for the return of six copybooks with poetry that he had written while in prison (in Yerevan before he was sent to the GULAG) and which were taken from him by the prison administration. Mahari mentioned in the document that he considered those poems the best he had ever written. Karen interpreted, `I asked Antonina if the authorities had honored his request.' In English, she added, `They promised to return them back to him but never did so. Oh, those were terrible times! Terrible!'

Another piece of bitter-sweet memorabilia was a painting by Ashot Sanamian of the cabin in which Mahari lived in captivity. An inscription reads below the painting, `In this house Gourgen Mahari lived and wrote, `Eritasardutyan Semin' [On the Threshold of Youth]. Mahari wrote a series of short autobiographical novels, Childhood, Adolescence, and On the Threshold of Youth. Mahari never finished the second part to On the Threshold of Youth. The three books reveal the author's life in his native Van and the exodus of Armenians to Eastern Armenia and his experiences in the early years of the young Republic.

|

|

Antonina Mahari (© K. Vrtanesyan/Groong) |

Thirteen years of Independence in Armenia have dealt a setback to the majority of people, especially the elderly. It is a day to day struggle for food, clothing and shelter. Antonina is not an exception to this plight, yet she made no complaints to me about her living conditions. Her comments and generalizations revealed an idealist beneath the surface.

Quick to share her opinions, she raged for a moment on the current war in Iraq and then apologized to me since I was her guest and an American. I appreciated her candor and responded to her apology by explaining an American idiom that appropriately describes her. `You shoot from the hip,' I said, and her countenance blossomed into a satisfying grin.

Personally experiencing her verve, I came to understand how she made a difference in Gourgen's life, first by sharing torment in captivity and then sharing intellect and integrity. His work is marked by optimism in the face of unimaginable adversity and this makes him and his writing extraordinarily valuable. To fully appreciate this man and artist, and therefore his life partner too, we need only to be touched by his words. In the last passage of his Autobiography (1963) he wrote, `Sixty years have been lived. If we consider that the conscious life begins at seven, and if we add to this the seven years of orphanages and streets and to these fourteen years the period of 1936-1954..there will remain to me twenty-eight years. But if at this very moment the most terrific and powerful of Jehovahs came in and sat in front of me, lit a cigarette and said: `I give you a second life. Trace it yourself from cradle to grave and your wish will be carried out. How would you like to live?' I shall answer Him without the slightest hesitation: `Exactly in the same manner as I have lived.'' (`Ararat'- Winter Issue 1979).

Antonina's tribute to her husband is this unpretentious museum- apartment where she has preserved her husband's memory and work. She has amassed memorabilia that document not only her and her husband's life experiences, but a portion, although dark, of Armenia's history. Antonina invited us to write our comments and sign the guest book, which we did with pleasure.

Upon reflection of more than a dozen museums that I have visited in Armenia, the House Museum of Gourgen Mahari [Kassian Street Bldg 3, apt 36 -4th Floor -27-15-92] was the most intimate and revealing by far. No finer docent can be discovered than the one who shared his heart!

|

|

Ruth and Antonina (© K. Vrtanesyan/Groong) |

-- Ruth Bedevian continues her visits to Armenian authors' House Museums around Armenia. Her articles in this series are at: http://www.groong.org/orig/armeniahousemuseums.html © Copyright 2004, Armenian News Network / Groong All Rights Reserved.

|

Redistribution of Groong articles, such as this one, to any other

media, including but not limited to other mailing lists and Usenet

bulletin boards, is strictly prohibited without prior written

consent from Groong's Administrator. © Copyright 2004 Armenian News Network/Groong. All Rights Reserved. |

|---|