Armenian

News Network / Groong

Raphael Lemkin And The Coining

Of The Word “Genocide”:

Miscellanea: Odds and Ends from Our Armenian-related

Notes

Armenian News Network / Groong

July 5, 2022

by Abraham D. Krikorian and Eugene L. Taylor

Probing the Photographic

Record

LONG ISLAND, NY

PrÉcis

What we have covered in this extended essay is essentially a

prospectus on the Armenian genocide. Rafał Lemkin, a

Polish Jewish jurist and lawyer coined the word genocide and circumscribed what it was and was not. He made it very clear that he knew the

Armenians were victims of genocide. We

maintain in this essay that all victims of genocide should be supportive of one

another. It is the evil genius of those who commit genocide to foster denial

and make the victims of these various persecuted groups see each other as

rivals to pity, and thus easy to dismiss as malcontents, exaggerators, and

subversives. News management and control

of media narrative have become fine arts among genocide deniers. We believe the arguments and imagery we

present are persuasive, grounded in historical fact and detail, and should

dispel the deniers. It is not a matter of

“We were the most victimized,”

rather, it is a matter of much greater general import. Not only those peoples who have been

victimized by genocide should be a matter for our concern, but of all

victimized peoples who deserve our interest and recognition in history. Names and definitions are important but not

the all-important element.

Introduction

One of the

objectives of this presentation is to fill in a few gaps of knowledge about the

life and work of Rafał Lemkin (Raphael Lemkin). Some emphasis is also given in the latter

part of this essay to how he came up with phrases like “the Armenian genocide” (spelled with a lower-case g or capital G) or “the Genocide committed against the

Armenians,” “the Turkish Genocide of the Armenians.”

One must state at the outset that it took

many years for the word ‘genocide’ to

come into being as a 20th century construct. The word was totally due to the initiative

and labors of Raphael Lemkin, a Polish Jewish jurist, and has unfortunately

evolved to the status of being accepted or used today without much serious

concern or introspection. In the early

period, the word or concept was barely known or bothered with by the public at

large, even the educated and professional public. The word has now become a matter of

international law, but to be frank, international law generally speaking has

few teeth and this ends up being a Godsend to specialist attorneys who can

argue the cases forever.[1]

What Can Be Said

About Raphael Lemkin

that is important

but has not been said before?

The answer is “Unfortunately, not much

that would be described as super-important.”

But there is ample opportunity to add bits and pieces to the story. There is a fair amount of general

biographical and bibliographical information on Raphael Lemkin available

online, so little need be repeated here in the body of this essay based on that

information. There are, however, many

Lemkin materials that are scattered throughout various print archives that are

still largely inadequately used or even essentially understudied or even

unstudied. One certainly wishes that

they were available for examination in a more ordered fashion. The fact that they are available at all is a

miracle in itself. Steven Schur relates

the dramatic story of the recovery of the Lemkin Archival materials that are

now in the New York Public Library.[2]

We ourselves have done some research in

most of the archives where Raphael Lemkin’s papers are preserved, but we have

always felt that the materials were by no means easy to study in the most

rational of manners. For one thing, his

handwriting is not very easy to read.

The typed pages are of course better, but they are often undated or

missing. It is also important to say

that there are points in the papers which cannot be substantiated by

corroborative research, or they may even be inconsistent and contradictory.

In one place, for example, to be found in

the New York Public Library papers, there is a biographical statement relating

to his experience coming to the USA and teaching. It says that he “proceeded to the United

States which he reached just before Pearl Harbor.” Now, every school child of our generation has

hopefully learned Roosevelt’s statement that December 7, 1941, was “a date which will live in infamy.” Archival records at Duke University Law

School indicate that Lemkin was in Durham, North Carolina in late April

1941. Just how the phrase “just before Pearl Harbor” got into the

record will have to await someone coming across it by chance. Perhaps in the grand scheme of things “just before” could be April and it is

thus a totally negligible point.

This quibble is but one trivial example of

how challenging it is to not slavishly follow what one encounters in

archives. One cannot always easily

decide what is important and what is not.

The Lemkin materials are voluminous, and it is one thing to admit that

many topics entail a complex narrative that must be elicited from the various

sources. Even so, it would seem that at

least some basic, verifiable, and verified information about a person who is

often so eulogized and applauded today would be well settled by now. Apparently, for Raphael Lemkin, that is not

necessarily the case. We spent more time

than we should like to admit tracking down the ship’s manifest for Lemkin’s

immigration. We were finally able to do

it at the Family History Library at Salt Lake City. Prior to that we had run into a number of

stumbling blocks. At least that is now

done and should put to rest the range of largely incorrect stories of his immigration.

(See below.)

Also, there are on occasion, multiple

copies, versions, and drafts, some in different locations. For us, getting only a few of them into some

sort of chronological order has been a major task despite “Finding Aids.” Some years back it was reported that there

was an ambitious plan to publish a catalog of Raphael Lemkin’s unpublished

works and correspondence as part of a comprehensive project. This was to be accompanied by a full-length

biography. Rabbi Dr. Steven Leonard

Jacobs of Tuscaloosa, Alabama undertook this herculean task. Even a cursory examination of a volume

published in 1992 by Rabbi Jacobs that derives from an untitled Lemkin manuscript, but titled and edited by Jacobs as “Raphael Lemkin’s Thoughts on Nazi Genocide.

Not Guilty?” (Edwin Mellen Press, Lewiston, ME.)

shows what an enormous undertaking such a project involves.

Before

continuing in our attempt to give at least some fresh perspective on Lemkin’s

life, we should perhaps start off with the point that the Polish spelling of his first name is Rafał, that is an l with a stroke through it.

This renders the pronunciation as “Raff’ow”

[as in ow that hurts!]. Raphael is the Anglicized form of his name

and is mostly used.[3] We have encountered only a couple of times in

correspondence where he is addressed as Rafal (no line through the l as ł).

Not unexpectedly, most of the coverage

that one finds on the Internet is largely derivative and some of it inexact,

sometimes totally wrong. Such basic

pieces of information as Raphael Lemkin’s year and ‘country’ of birth etc.

present inconsistencies, just as the period when he first entered America, and

traveled to North Carolina. His year of

birth is sometimes wrongly given as 1901 rather than the correct date of 24

June 1900 (See Fig. 8.). He died 24

August 1959 in New York City — he did not have a heart attack in his apartment,

by the way, as has been said more than once.

To our annoyance, the full medical record

dealing with his death is not accessible in NY State to non-relatives. That shows how silly these things can

get. The hypocritical pretense that

privacy is all-important is a joke. Some

individuals who are dead may not have living relatives. No one seems to have worried about that. ADK raised such a stink that we would be glad

to hear that policy is no longer in place and has exceptions.

Raphael Lemkin wrote himself that he was

born in 1900 in Bezwodne, district of Bialystok,

Poland.[4]

To be a bit more informative one might

today say that Lemkin was born in what was once referred by some Old Country

residents of the area as the “North-West,” that is, in what was referred to as

the ‘Pale of Settlement’ in the old Russian Empire. On some period maps,

the international boundaries of the region are referred to as “Russian Poland” with ‘White Russia’ being a significant but

not all-embracing element. The Kresy (from the

Polish word for frontier or borderland) is another expression that one

encounters, but the location and composition of the Kresy

varied as well over time. So much for

frontiers and the vicissitudes of geography.

Today the place that

Lemkin spelled Bezwodne and which he allocated to Poland when

he was writing his curriculum vitae for use in America, is given as Bezwodna in

Belarus, roughly speaking near to where Poland and Lithuania now meet. In the time of the Polish Republic

following 1920 Bezwodne was in the Białystok district.

As of January 1939, the Grodno oblast [administrative region] was part

of Poland.[5]

Part of a curriculum vitae produced by

Raphael Lemkin himself, emphasizing his broad experience and professional

activities is given below. Readers will excuse some repetition of what has

already been said.

He

was born in what was historically known as Lithuania or White Russia. He attended the University of Lwów and then the University of Heidelberg studying

philology and languages – ending up mastering nine languages. He was a member of the faculty of the Free

University of Warsaw, Public Prosecutor of the City of Warsaw, member of the

House of Governors of the Bar of Poland, a member of the Polish Board for

Codification of Legal Codes, a member of the International Committee for the

Unification of Penal laws of the United Nations (Fifth Committee) 1931-39;

representative of Poland on the Board of Governors of the International

Association of Penal Law, Paris, 1932-1938; representative of Poland at the

International Juridical Congress in Brussels, Paris, Copenhagen, Rome, Palermo,

Prague, Cairo, Amsterdam, and Budapest.

He was author in Polish: The Polish Penal Code (with Justices Janusz Jamont and Emil Stanisław Rappaport (2 volumes, Warsaw, 1932; The Judge

Confronted by The Modern Criminal Law and Criminology (Warsaw, 1933); Amnesty

(Warsaw, 1933); Financial Law (Warsaw, 1937); The Russian Penal Code (Warsaw,

1928); The Italian Penal Code (Warsaw,

1929); in French: The Regulation of International Payments with preface by von

Zeeland (Paris, 1939); in Swedish: Exchange Control and Clearing (University of

Stockholm Lectures, 1940-1941). Author

of numerous monographs, papers, and articles on criminal law, penology, and

international monetary problems in Polish, French, German, Italian, and

English. He taught for one year at the University of Stockholm and from there,

via Eurasia and Japan proceeded to the United States.

This brief accounting gives a broad

perspective of a man with a great deal of experience, especially for someone so

young. Would-be detractors who suggest

that he was ‘a nobody’ are very misinformed.[6]

For our more immediate purposes here, many

might say that it would suffice to say that Raphael Lemkin was a jurist, a

Polish Jew who immigrated into the U.S.A. in 1941 through a series of rather

amazing events, assumed an appointment in mid-April 1941 at Duke University

School of Law in Durham, North Carolina that had been pre-arranged by a friend

on the Law faculty, and by the time of the 1949 TV broadcast “UN Casebook XXI: Genocide” through

which he became better known and recognized as a public figure, he held a

teaching post at Yale University.

It seems appropriate to now present some more relevant details

on his personal history. Raphael was the

second of three sons. His older brother

was named Elias and his younger brother was Samuel. His father was a tenant farmer, said to be

somewhat unusual at that time for a Jew.

His mother (née Bella Pomeranz)

has been described as a cultured, highly intelligent woman.

Professor

Ryszard Szawłowski has

pointed out a number of nonsensical statements [see endnote 6 cited above] that

exist in various biographical accounts, and we ourselves know that these errors

have been sustained more than a few times both in print and in lectures. For example, any notion that Raphael Lemkin

lived under Nazi occupation is just that, a baseless notion. Lemkin never lived under German

occupation. (Fair to say that the Polish

administration was sympathetic to Hitler, even pro-Hitler, from 1933 right up

to the time of invasion in 1939.) Lemkin

practiced and taught law. The mentality

was that the Nazis were anti-Russian, and that suited more than a few

Poles. He lost his job when he returned

to Warsaw in 1933 after trying to get the League of Nations interested

seriously in crimes of “barbarity.”

(That was a lost cause.) Neither

was Lemkin part of the Polish underground movement. His family was apparently murdered by the

Nazis in 1942, at a time after which Lemkin had been and was in the United

States, that is after April 1941.

So

far as we can determine, the ‘only’ atrocities that Lemkin saw with his own

eyes (and they were certainly barbaric enough for anyone to witness) entailed

the following which we quote from a magazine article by well-known journalist

Herbert C. Yahraes Jr., published in Collier’s magazine in March 1951pg. 29:

“With the Nazi invasion of Poland in

1939, Lemkin took refuge with hundreds of other Poles in a vast forest. There he saw the Germans bomb a refugee train

drawn up at a nearby village. Several

hundred children who had packed the train had tumbled out and were eating

breakfast. Telling about it, Lemkin rubs

his hand nervously over the arm of his chair.

“Then as the planes came over,” he says quietly, “and destroyed

them.” He looks up. “Is it any wonder I couldn’t forget my idea?”

[of developing and putting in place

legislation against the crime of barbarity.]

For

us, this indeed qualifies as his ‘personal experience’ but does not reflect

personal experience so far as ‘The Holocaust’ is concerned, as some have

claimed, not unless one wants to recast dramatically when ‘The Holocaust’

against the Jews and Slavs and Roma and Sinti etc. began.

Loss Of Raphael Lemkin’s Family During The Nazi Horrors

An

important piece of information about Raphael Lemkin learning of the death of

his relatives as a result of the Nazi horrors may be found showcased in the Collier’s magazine article by Yahraes, referred to above entitled “He gave a name to the world’s most horrible crime.” The article clearly seems to have relied on

an interview or interviews, and portrays Raphael Lemkin in a very human light,

rather than in the more usual serious, even stolid way in which he is

characterized in most other articles.

See below.

Here

we will attempt to visit anew and very briefly the matter of what motivated

Raphael Lemkin to coin the word “genocide.” This has been approached, or at least touched

on by a number of writers in various and sundry incarnations of the whole. However, we should strive towards a

perspective that is as accurate as possible a perspective and get some timing

of events into a proper time sequence.

There are, of course, as in any attempts of synthesis of the sort under

consideration here, many pitfalls that confront one. Methodological complexity is the order of the

day.

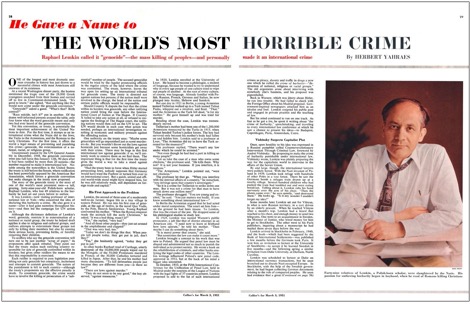

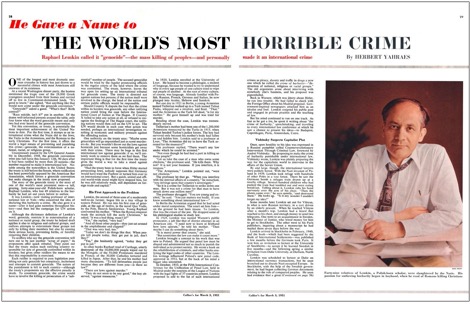

Figs. 1 and 2 below are from Herbert Yahraes “He Gave A Name To The World’s Most Horrible Crime.” Raphael

Lemkin called it “genocide” ̶

the mass killing of people, and personally made it into an international

crime, Collier’s magazine March 3,

1951 pgs. 29, 56-57.

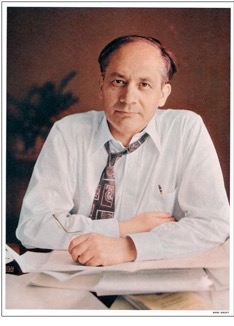

Fig. 1.

Double-page spread that opens journalist Herbert Yahraes’ excellent article.

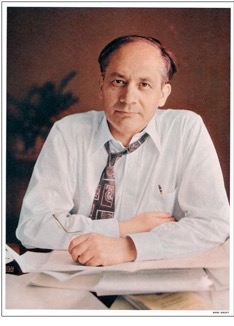

Fig. 2.

Enlargement of what we think is an attractive color

photograph by Hans Knopf of Raphael Lemkin in a somewhat pensive mood.

Raphael

Lemkin speaks quite directly on the matter about the murder of his relatives to

the journalist Yahraes. He asks, for instance, “If you mean do I know which went into the gas chambers, and which the

Germans starved to death someplace else, no, I don’t know that” (Yahraes 1951 pg. 56).

It

has been related that Lemkin needed to be hospitalized 20-26 July 1946 at the

U.S. Army Medical Hospital in Paris as a result of hypertension related

ostensibly to stress. We have not yet

checked the records in the United States National Archives of the Paris

hospital, but it has also been stated outright, or at least implied, that his

hospitalization was in Nuremberg. Cooper

(2008 pg. 72) says “Distraught at being

unable to trace any members of his family from Poland and suffering from high

blood pressure, Lemkin was confined to a military hospital.”[7]

Whatever

the sad specifics, it seems quite safe to say that it was considerably after

his release from hospital in Paris that Raphael Lemkin learned about the fate

of his family. This is, therefore, well

after Lemkin’s “Axis Rule…” appeared

in print. Accordingly, because the

hospital stay was in 1946 and “Axis

Rule…” was published considerably earlier in late 1944, it would appear

wrong to try to make the case that Raphael Lemkin’s coining of the word “genocide” is directly related to his

learning about that personal tragedy.

Moreover, coining the word certainly had nothing to do with “The Holocaust” in the strict use of

that expression. “The Catastrophe” or sometimes “The

Great Catastrophe,” Yiddish speakers and writers use “umkum” or khurbn

-sometimes pronounced as if it ended with an “m.” ” Umkum means

‘catastrophe’ or ‘destruction,’ ‘total destruction’ or even ‘war’ etc.,

depending on the context. (We thank Dr.

Agi Legutko, Director of the Yiddish Language

Program, Columbia University.) The

almost universally known expression “The

“Shoah” (‘Calamity’ in Hebrew) was eventually replaced, in America

especially, by “The Holocaust” only

considerably later.[8]

No

clear-cut information on any decision to annihilate all European Jewry had yet

been made, certainly known about at large when Lemkin was cogitating or

struggling with a name for the ‘crime

without a name.’ The point should be

made here, however, that Raphael Lemkin may well have believed that he ‘saw the writing on the wall’ rather

early. He recalled the pogroms he heard

of as a kid growing up. Litvak (1991)

pg. 68 says “It should also be remembered

that during the first half of 1940 there were only a few extreme pessimists who

foresaw the “final solution” as it was revealed in 1942.” There is little doubt in our minds Raphael

Lemkin was one of these.[9]

Recall

also that Raphael Lemkin’s emerging (and ultimate) definition of genocide was

broad. It is not insignificant that he later wrote considerably afterwards, that he “started to collect decrees of occupation

which had reached Sweden by way of occupied Europe. Some of these decrees, like that of the

German military commander in Serbia which had already in April 1941 established

a death penalty for hiding Jews and Gypsies, foretold the plan of committing

genocide.”[10]

Readers of our postings on Groong, the Armenian News Network will

see that we ourselves have always tried to be quite specific in our

wording. As a jurist Raphael Lemkin

necessarily saw things as legal issues, not from the perspective of a

historian, and certainly not as one working in today’s environment, either academic

or political.

Raphael Lemkin’s compilation of “Key Laws, Decrees and Regulations Issued

by the Axis in Occupied Europe,”

dated December, 1942 produced for the “Board of Economic Warfare, Blockage and

Supply Branch, Reoccupation Division” under The locator “RR-8 RESTRICTED COPY

No. (in our case seen as “no 88”) and stamped in red “From War Dept. Liaison

Office, Board of Economic Warfare” says: “This

collection was compiled by Dr. Raphael Lemkin partly when serving on the

faculties of the Universities of Stockholm, Sweden, and of Duke University,

North Carolina, and partly when serving as a consultant with the Board of

Economic Warfare.”

His preface begins: “The laws and decrees promulgated by Germany in the subjugated

countries of Europe, vary according to the policy which Germany has sought to

impose, and the problems which Germany has been forced to meet.” Lemkin’s work gives an excellent, brief

overview of the anticipated perspective on Nazi-generated legal frameworks for

persecutions in their occupied territories.

The worst of the ordinances in Lemkin’s compilation is in Serbia where

the death penalty is to be imposed on anyone who hides Jews or accepts material

goods for safekeeping etc.[11]

Putting

aside for the moment the nascent horrors as they were developing in

Nazi-controlled territories, we will continue with our sketch of Raphael

Lemkin’s biography as derived largely from the article by Professor Szawłowski and pieces of Raphael Lemkin’s own writings.

[see endnote 6 for full reference.]

When

Hitler invaded Poland on 1 September 1939, Lemkin left (escaped is perhaps more accurate) Warsaw on 6/7 September as did

thousands of other men. This was in

response to an order for able-bodied men to head East, where they would join

the army. There

Lemkin “encountered the Soviet aggression against Poland that took place on 17

September.” (That was only 16 days after

Hitler invaded Poland. The invasion by

the Soviets did not last long however because the Germans took over

completely.) Lemkin was detained by the

Bolsheviks but was subsequently released.

Had they known his real identity they would have arrested him and sent

him to a gulag for his hostility and vilification of the Soviet criminal legal

system in the course of his professional work.

After this, Lemkin stayed with his parents for a short while and got to

Wilno [Vilna] (in Poland but which was then occupied by Lithuanians, today

Vilnius, Lithuania). He escaped from

Lithuania to Sweden as a refugee in February 1940, remained there for more than

a year and even lectured at the Stockholms Högskola. His

Swedish became good enough to publish a book based on his lectures entitled “Foreign Exchange and Clearing.”

Exactly

when he left Sweden is not certain, but it seems reasonable that it was early

in 1941.

Raphael

Lemkin managed to get into America through his connections with Professor

Malcolm McDermott of the School of Law, Duke University, Durham, North Carolina. (They had met in Warsaw in 1936 and had

collaborated in publishing in 1939 an English version of a small book on the Polish Penal Code of 1932 and Law of Minor

Offences.) Raphael Lemkin is said to

have been “welcomed on 18 April 1941” at Duke.

(This exact date seems not to be formally confirmable, but it must be

very close, if not exact, since there is a news release found at Duke

University Law School Archives dated 24 April of his being engaged to teach

Roman and International Law.) Lemkin’s

long journey from Sweden had entailed coming to America by going clear across

the Soviet Union (Trans-Siberian Railway), eventually to Yokohama, Japan and

entering the U.S.A. via Seattle, Washington on 18 April 1941.[12]

We

shall now take the liberty to jump ahead in the broad scheme of things and give

some coverage to a marker in Warsaw and glean what we can from it.

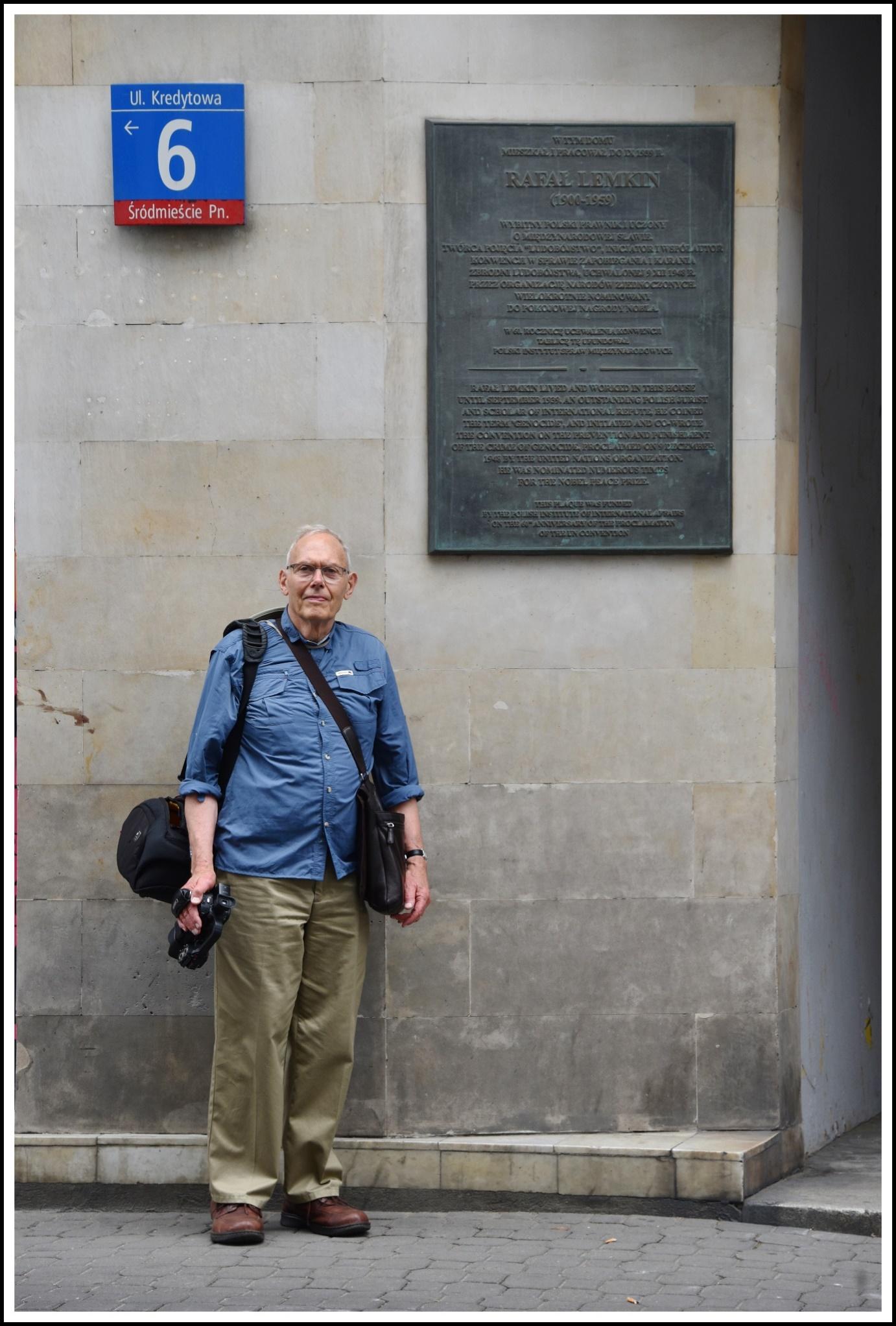

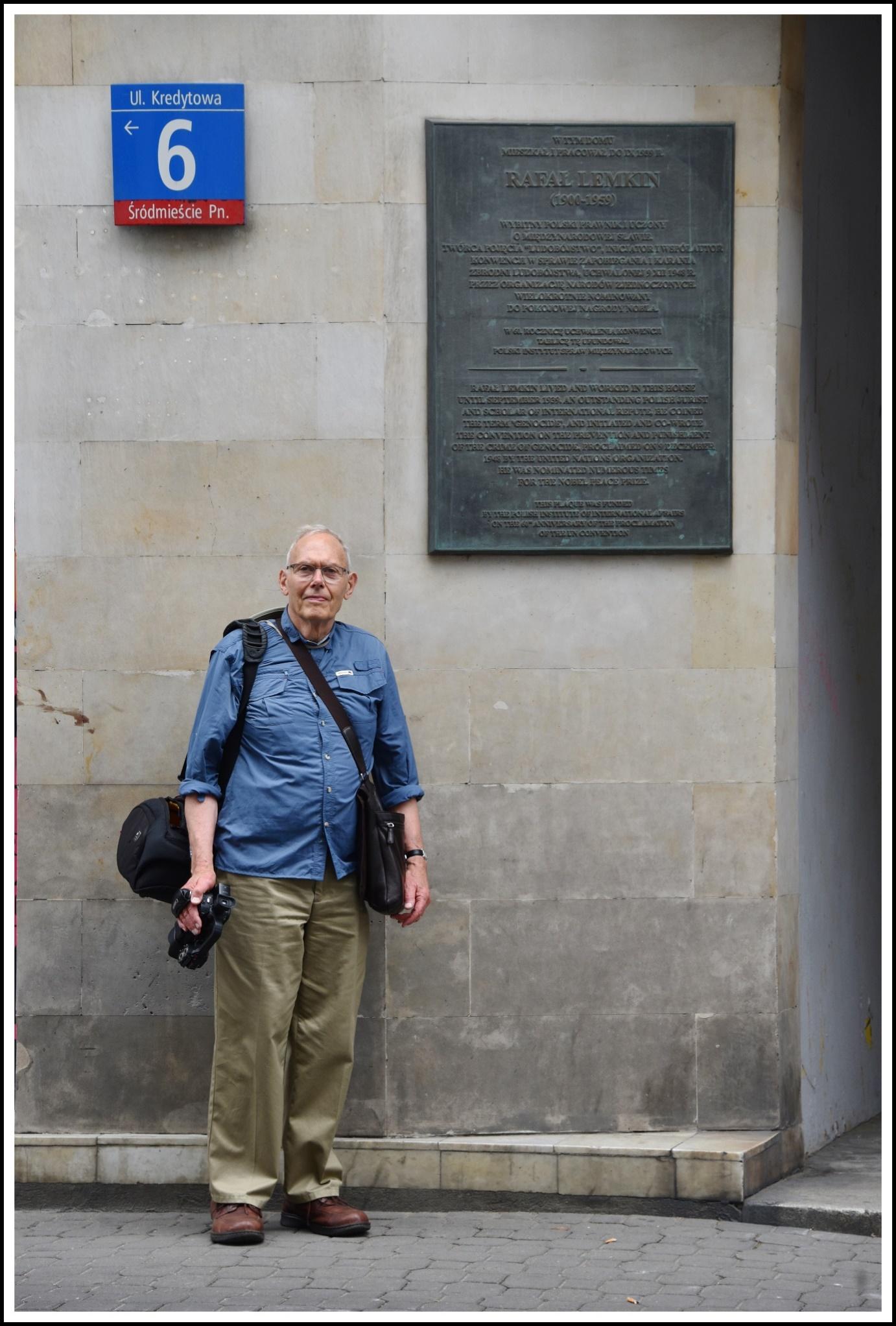

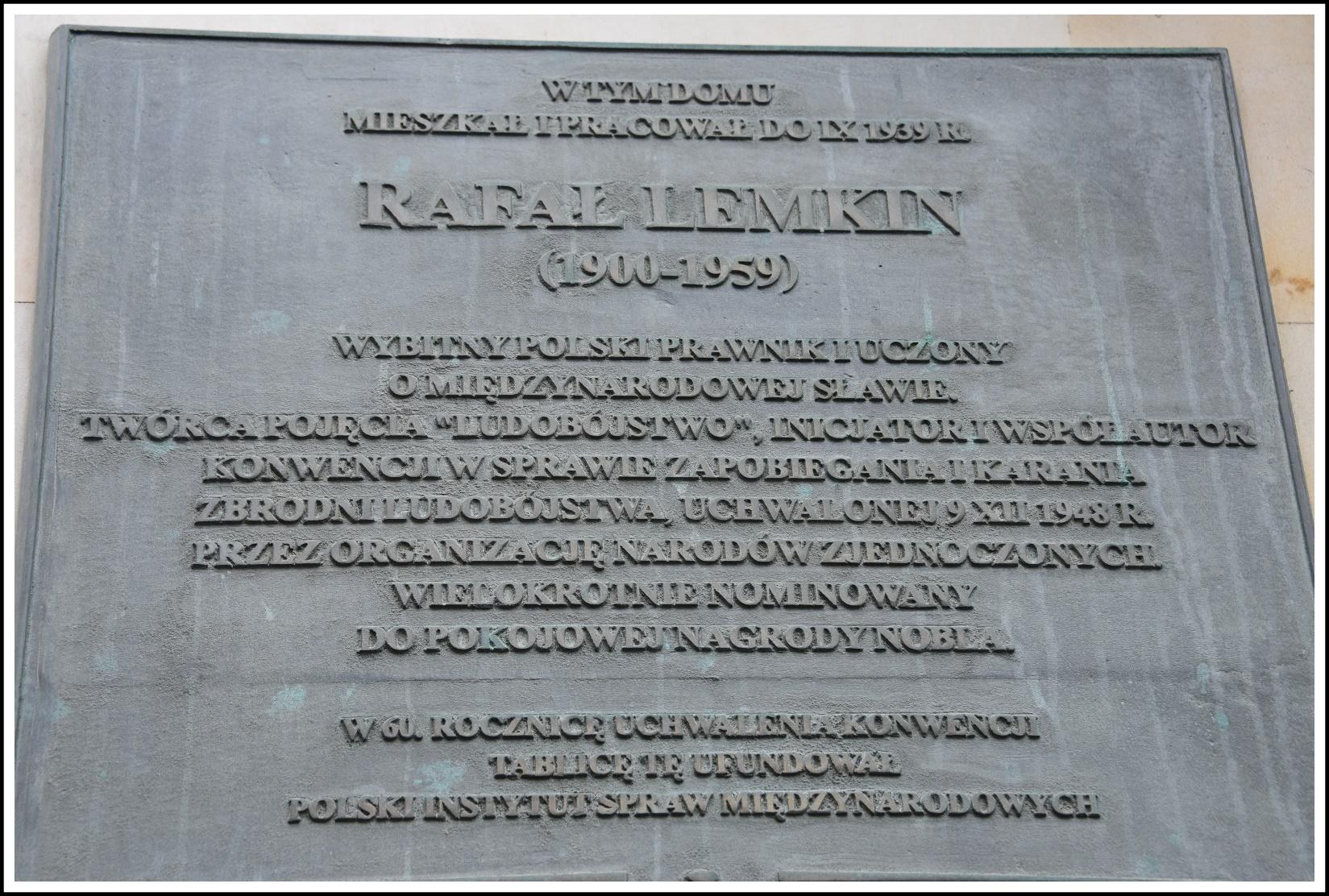

A Plaque For RafaŁ Lemkin In

Warsaw

As so often happens, markers are put up in

places with which a particularly important or well-known person was

associated. Some of these are very

simple, others are quite elaborate. If

one goes to Warsaw, Poland one can find a building complex which survived World

War II that bears a plaque honoring Raphael Lemkin. See Figs. 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, and 8 below.

We were fortunate enough to see the plaque

in Warsaw when we visited this city as part of a trip as tourists to the Baltic

Capitals. If one is unable to make a

personal visit, one can amazingly see through the miracle of Google Earth the

bilingual commemorative plaque placed on the outside of the then fairly upscale

apartment house that Lemkin lived in at 6 Kredytowa

Street for several years until 6/7 September 1939. His name is spelled in Polish and English as Rafał Lemkin. [It is

a common first name for boys and derives from the Hebrew “God heals” or some such.] Wikipedia shows another close-up of the

plaque see: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Rafal_Lemkin_plaque_PISM.jpg.]

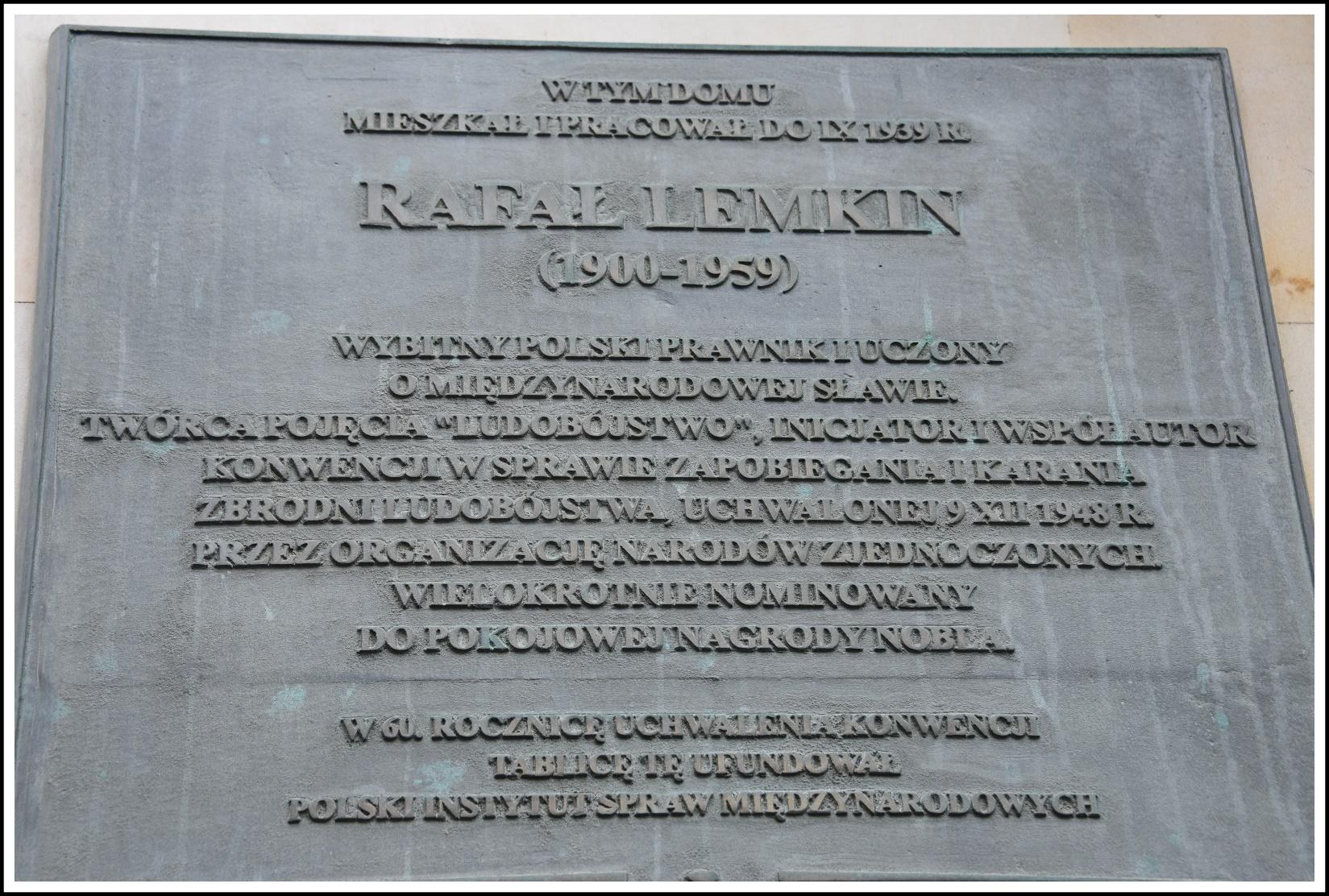

Fig. 3.

Building on Kredytowa Street where Lemkin lived in Warsaw, Poland. Fig. 8 shows plaque in some detail.

The awning on

the right indicates a ‘travel’ agency.

Fig. 4.

Eugene L. Taylor

(6 ft. tall) standing by Lemkin plaque on

the building where Lemkin lived.

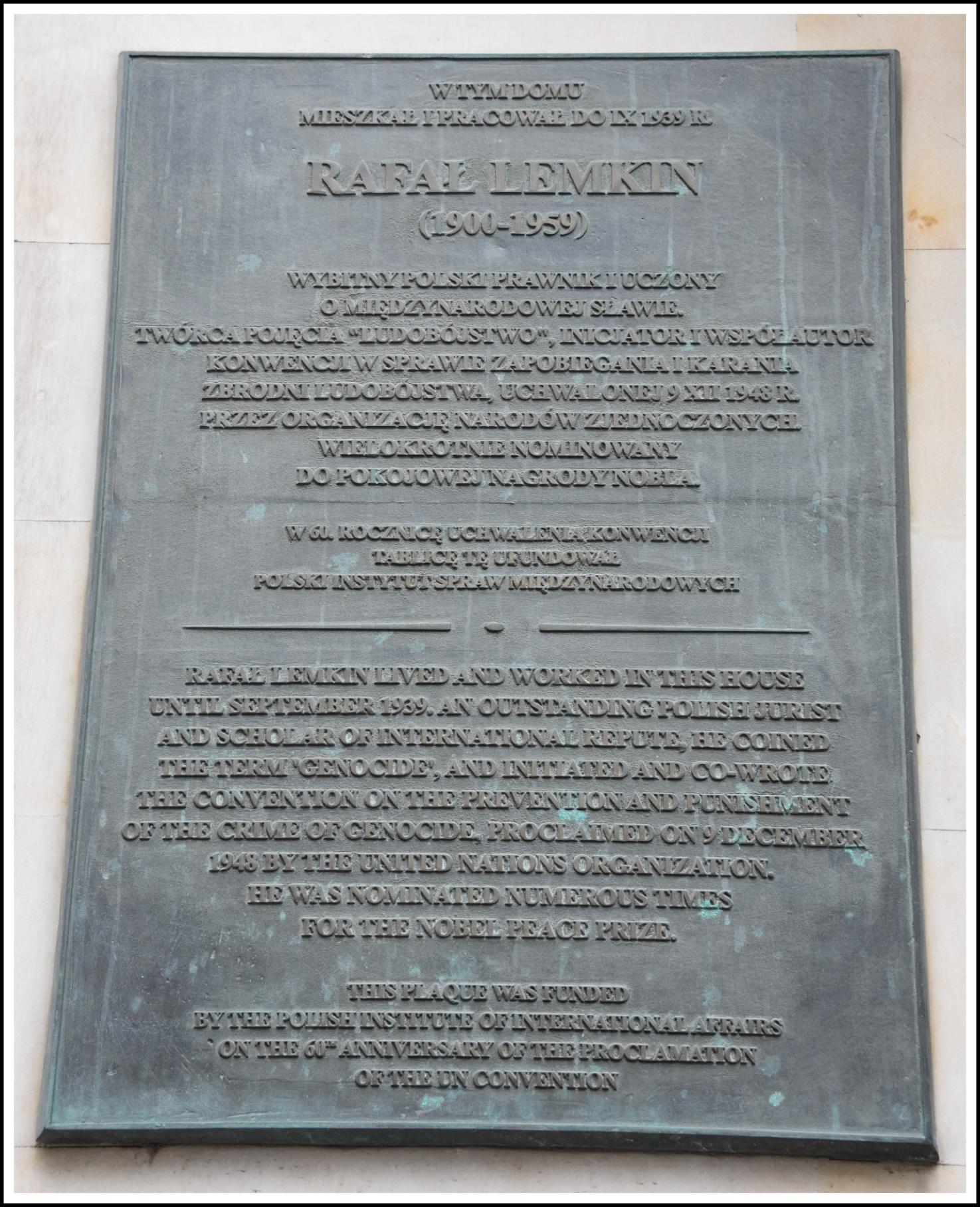

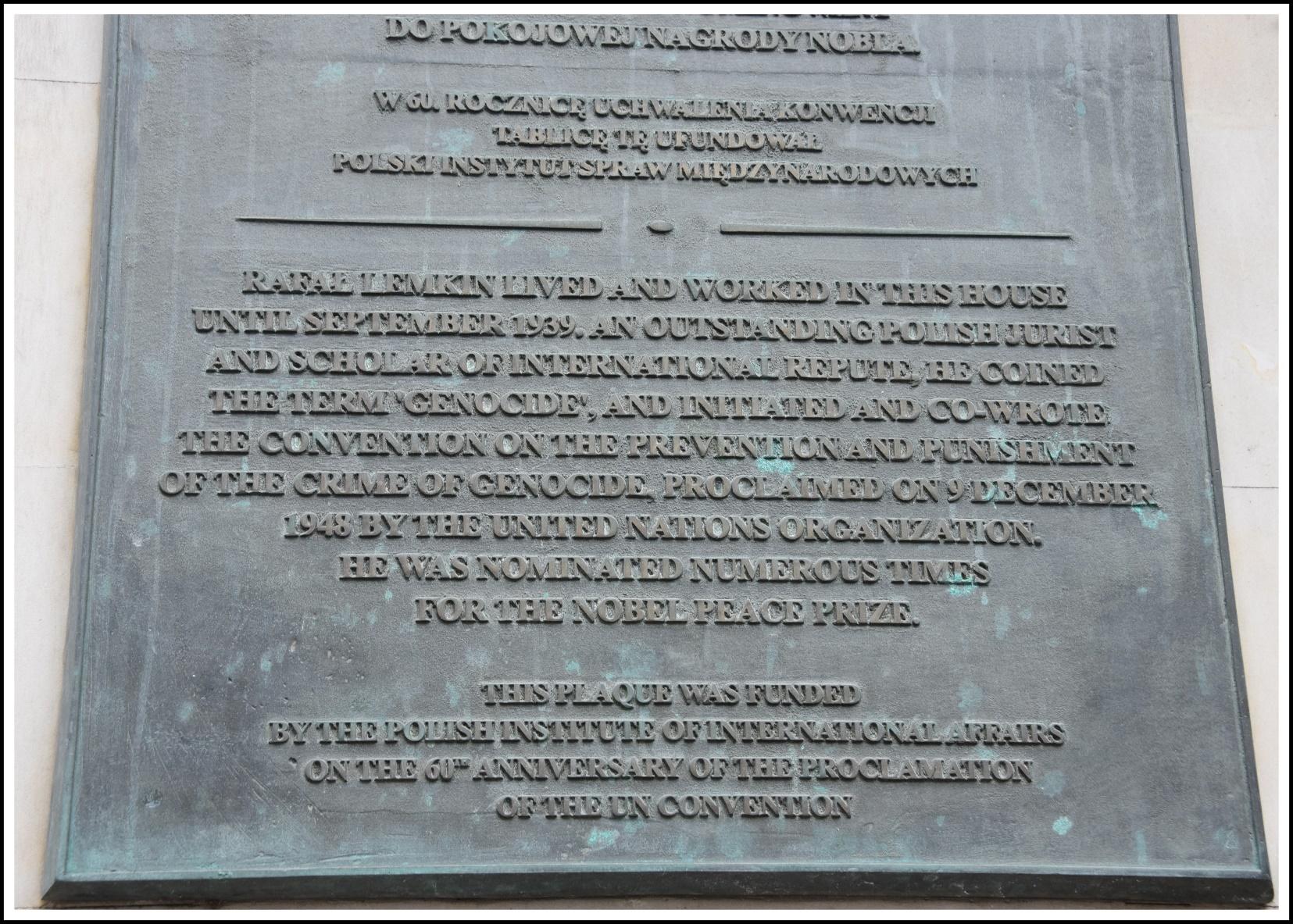

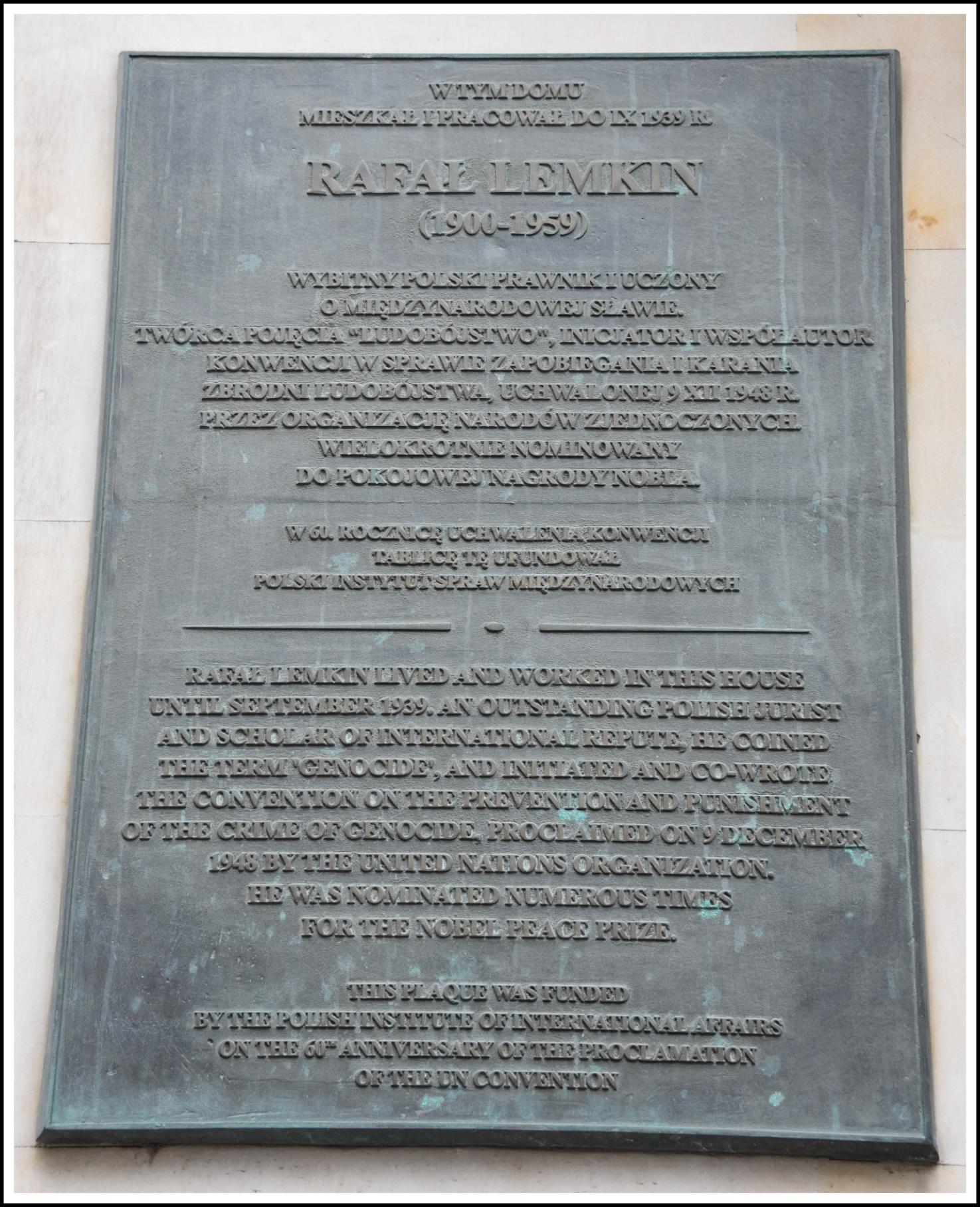

Fig. 5.

Closer view of

Lemkin plaque on the front of the building.

Fig. 6.

Lemkin plaque in

Polish and in English on the front of his residence in Warsaw.

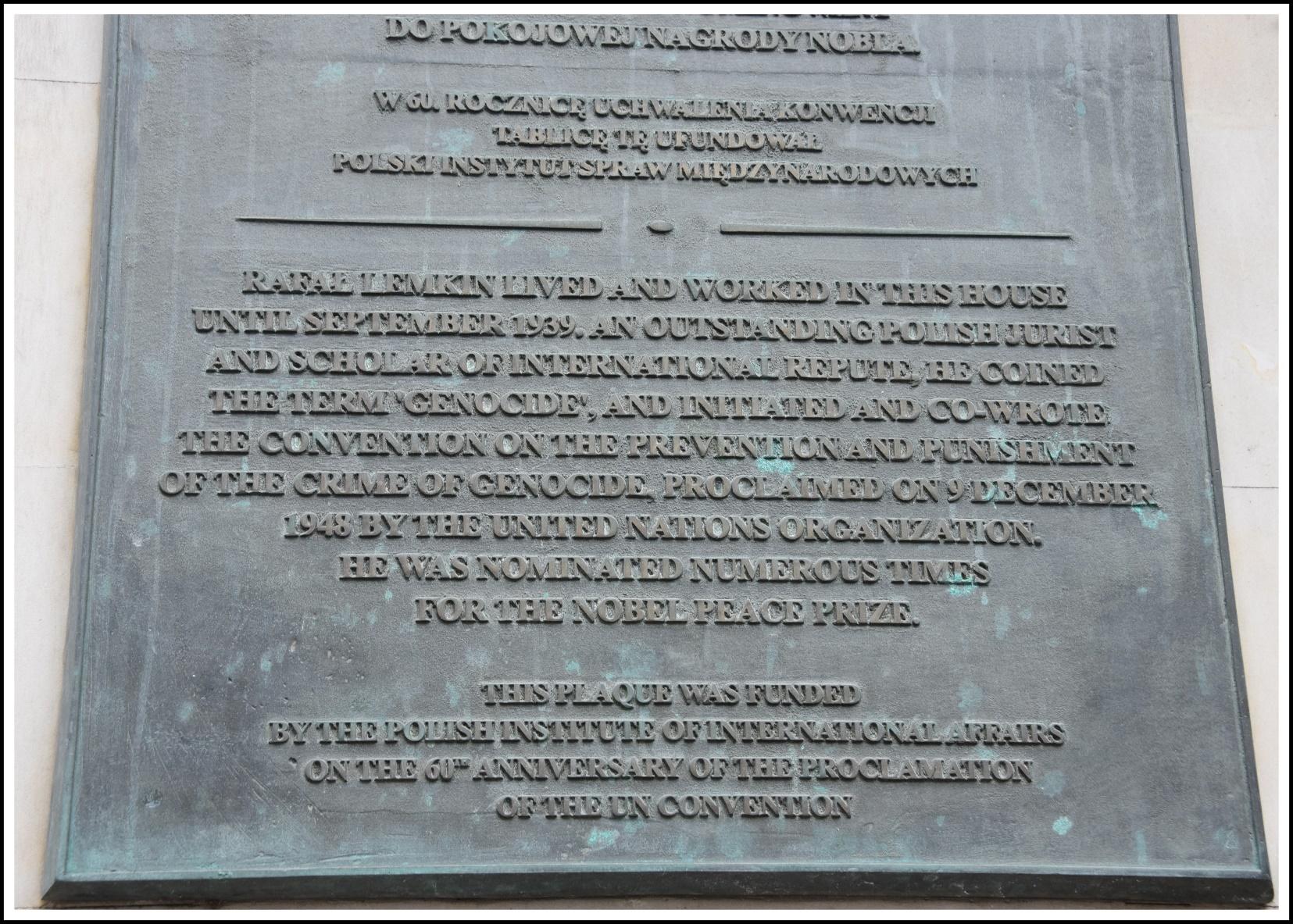

Fig. 7.

Close-up of the

English text on the Lemkin plaque.

It might be a

bit optimistic to suppose that many people will know that the Genocide

Convention

was adopted on

December 9, 1948, and that the 60th anniversary

would be marked

on December 9, 2008.

Fig. 8.

Close-up of the

Introduction in Polish on the Lemkin plaque.

It was noteworthy to us that no one in the

area or in the shops in the building complex knew anything about Lemkin, its

one-time resident, who eventually became “famous” for instigating and

initiating the Genocide Convention. Indeed, “No

one is a prophet in his own land.” (Holy Bible Luke 4:24).

Lemkin’s Burial

Place

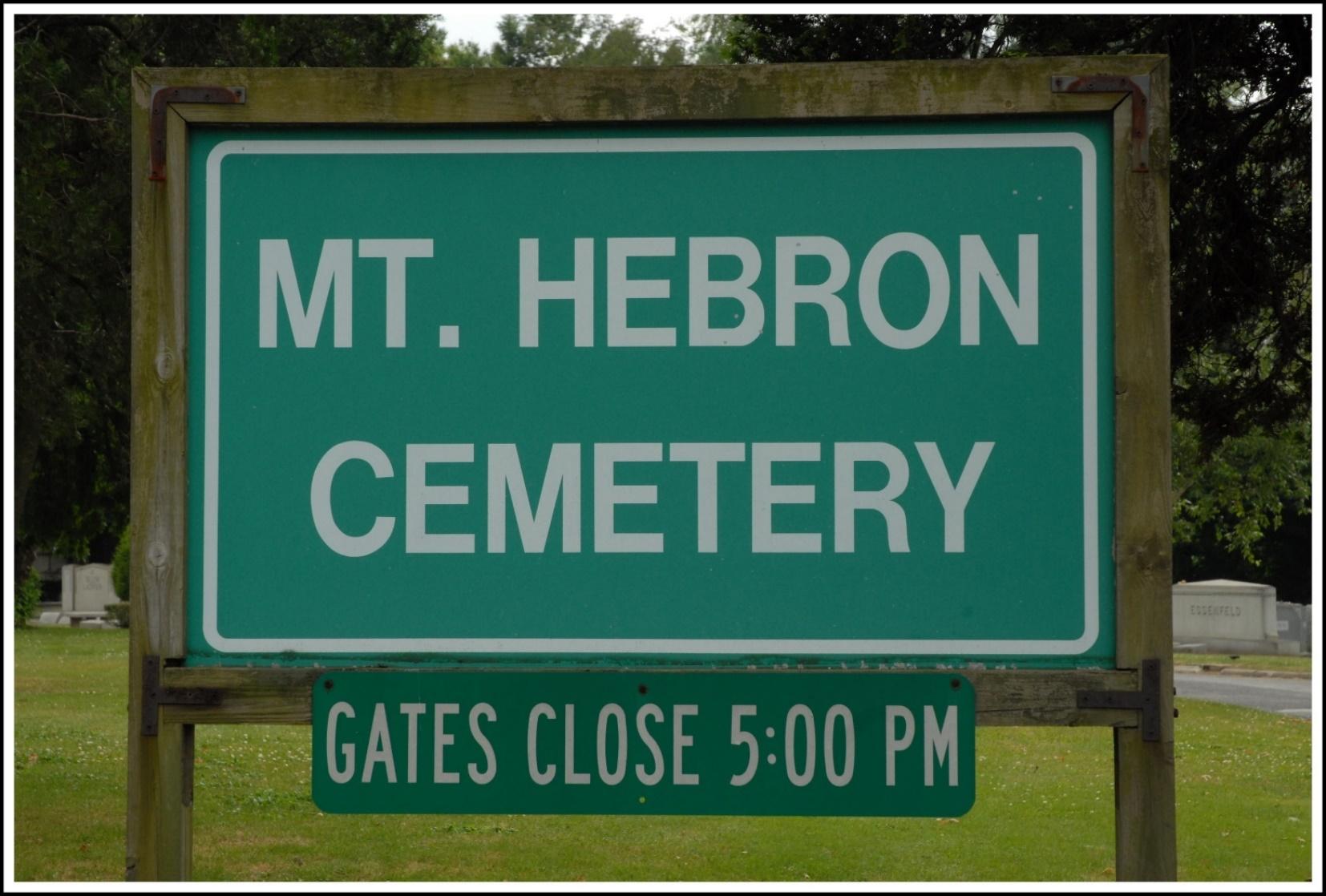

We encountered the same situation a dozen

years ago when we undertook a visit to Lemkin’s gravesite in the USA at the Mt.

Hebron Cemetery in Flushing Queens, on Long Island. It was as if we were seeking the grave of

someone who mattered very little or nothing to the world at large. (Apparently that has changed slightly in

recent years.) When we visited Mt. Hebron

Cemetery 2010 it was a major project to locate the gravesite, and bird droppings

soiled the stone and site in general.

Fortunately, we had some water and cleaning tools available to clean off

the grave marker a bit before we took photographs.[13]

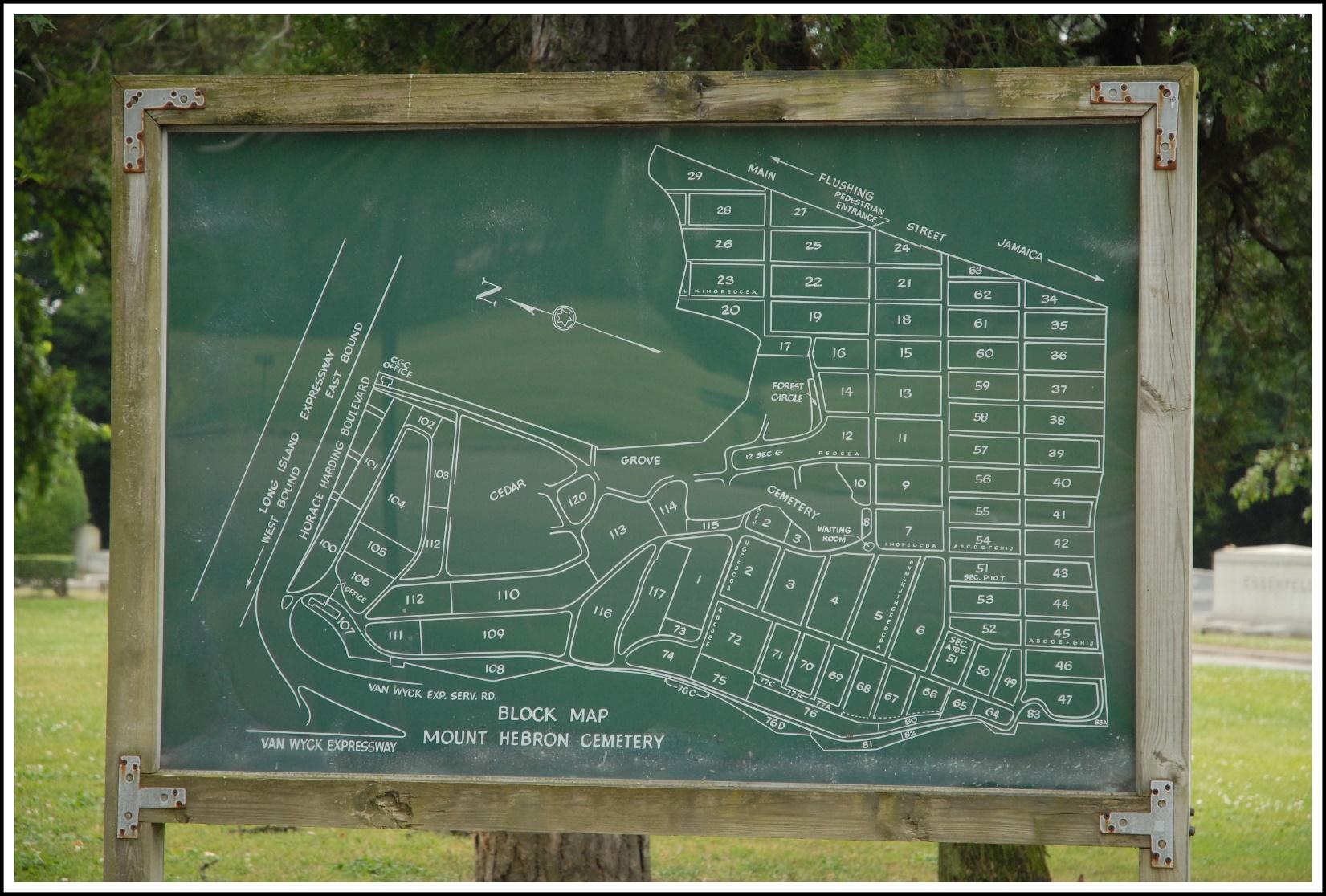

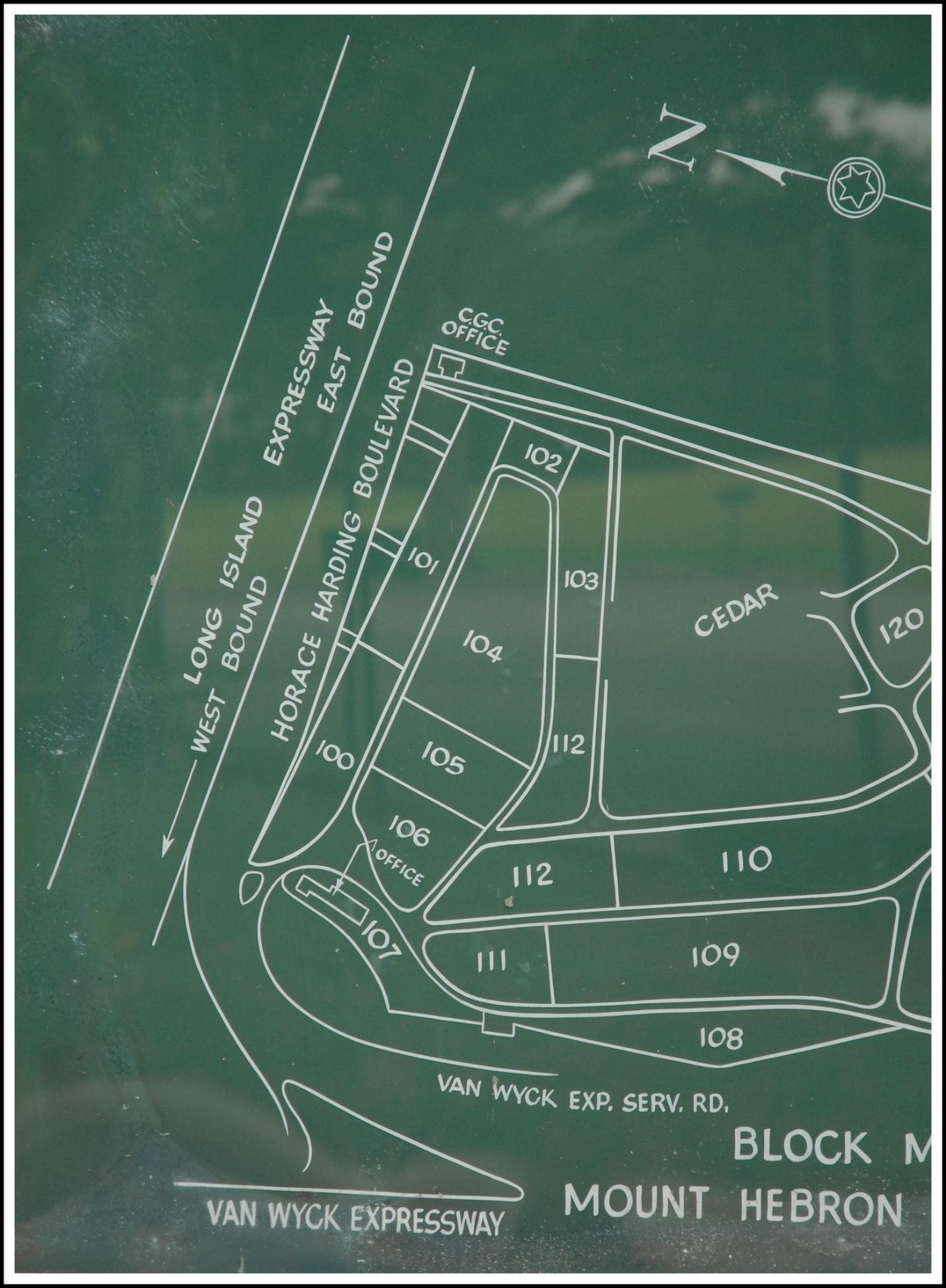

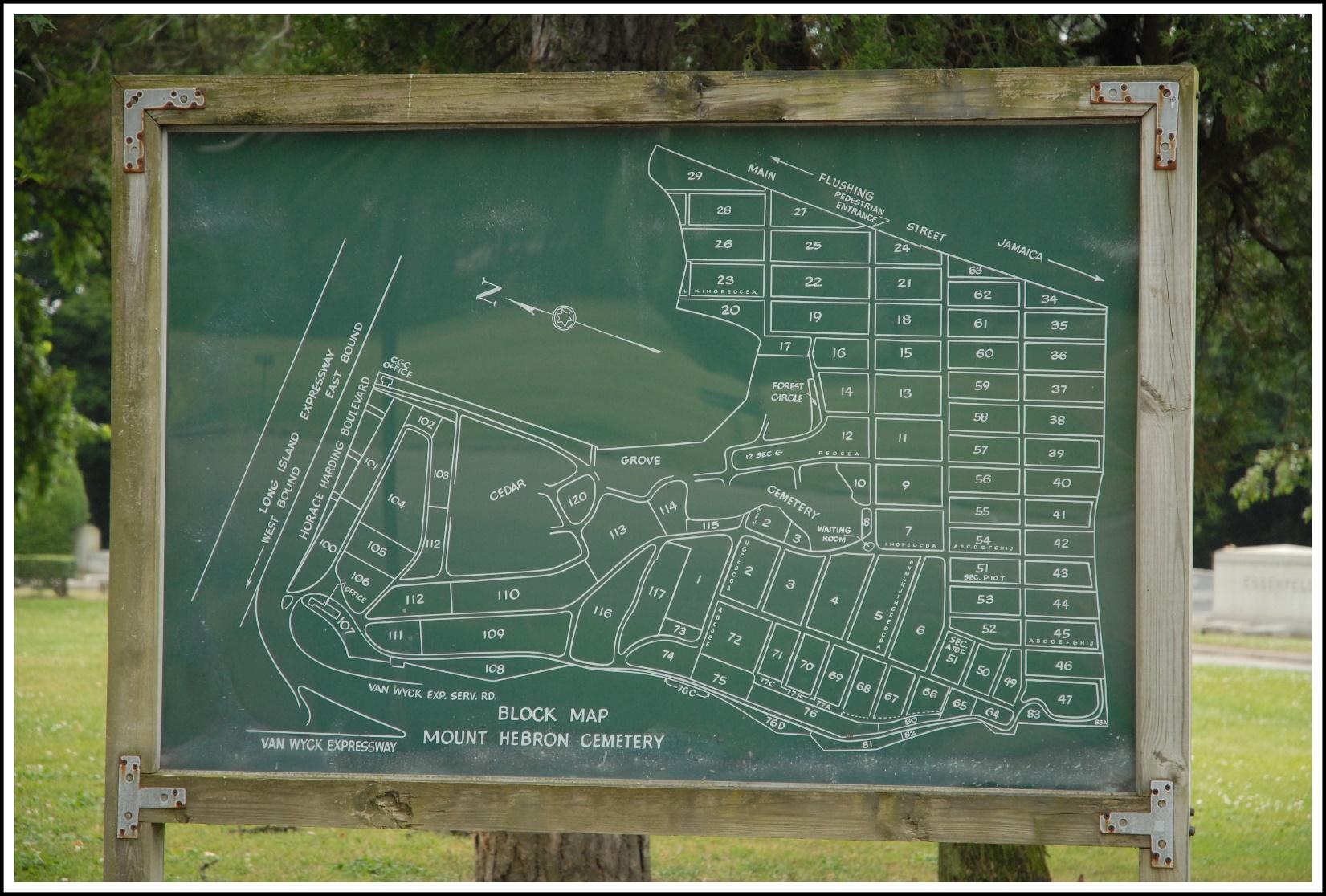

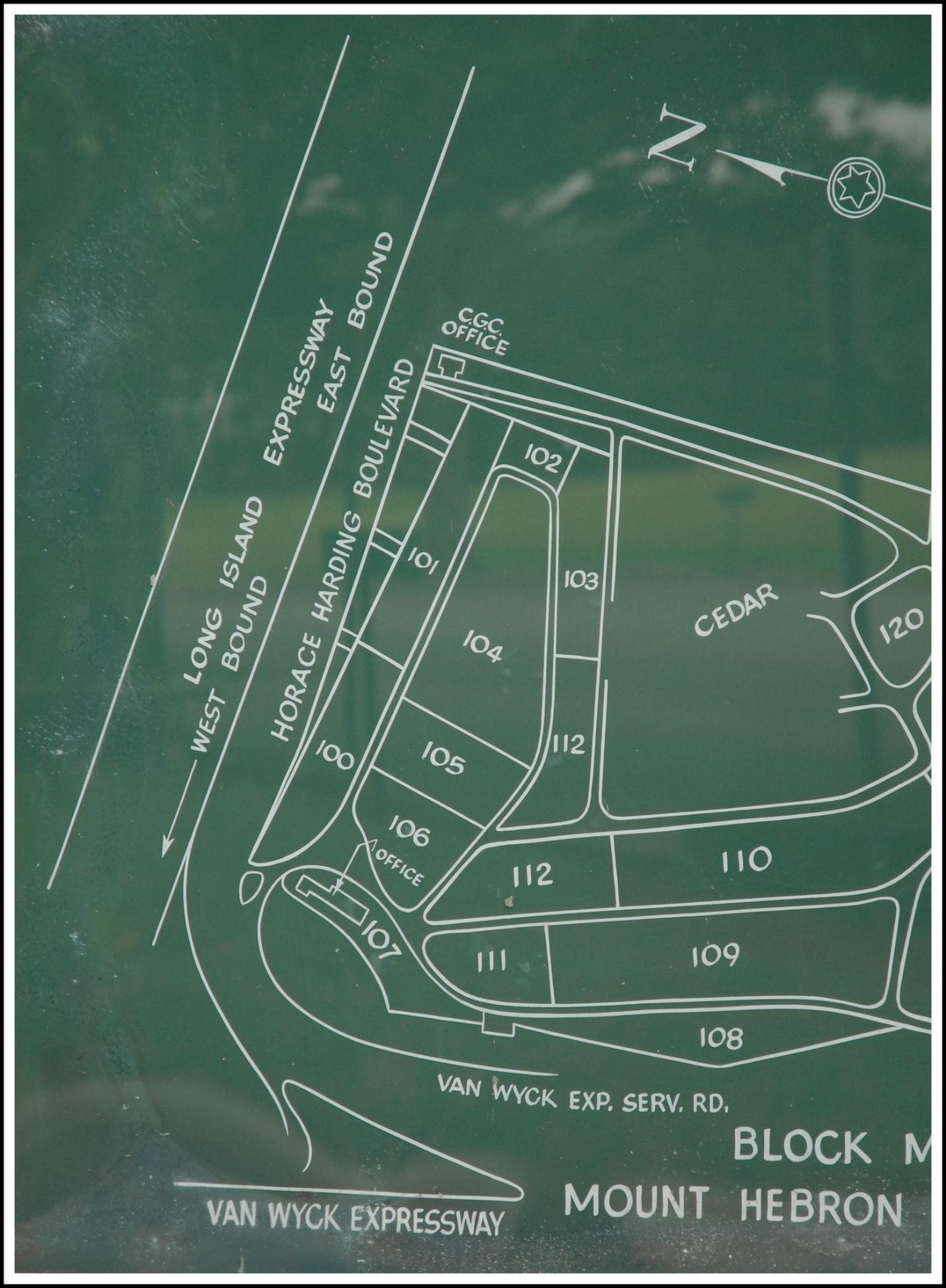

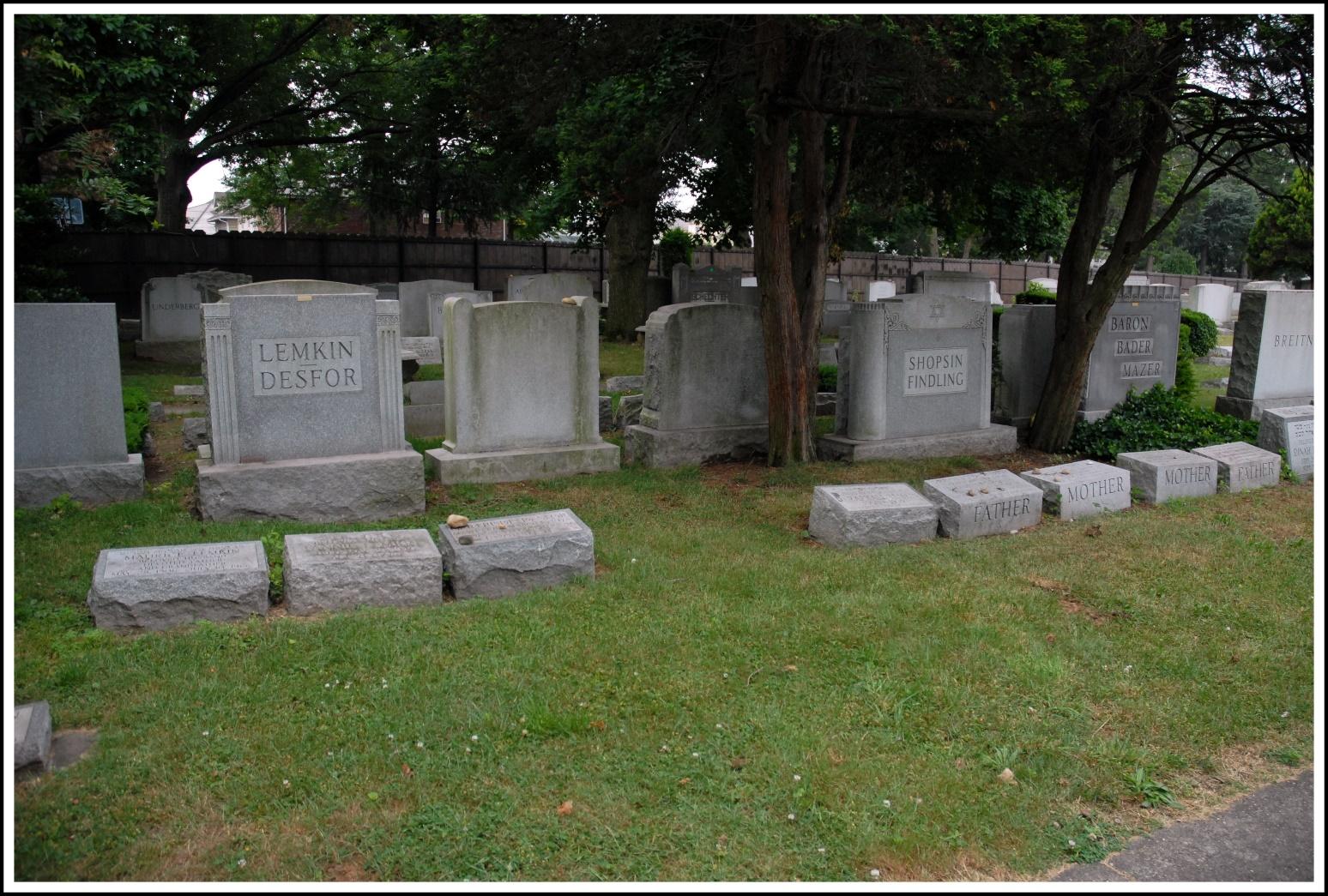

Fig. 9.

Fig. 10.

Note especially

Block 101 at around 8 o’clock on the left side of the locator map.

(See enlargement Fig. 11.)

Fig. 11.

Fig. 12.

Shows what a

challenge it would be to seek out a gravesite at Mount Hebron Cemetery without

specifics.

There are an

immense number of graves.

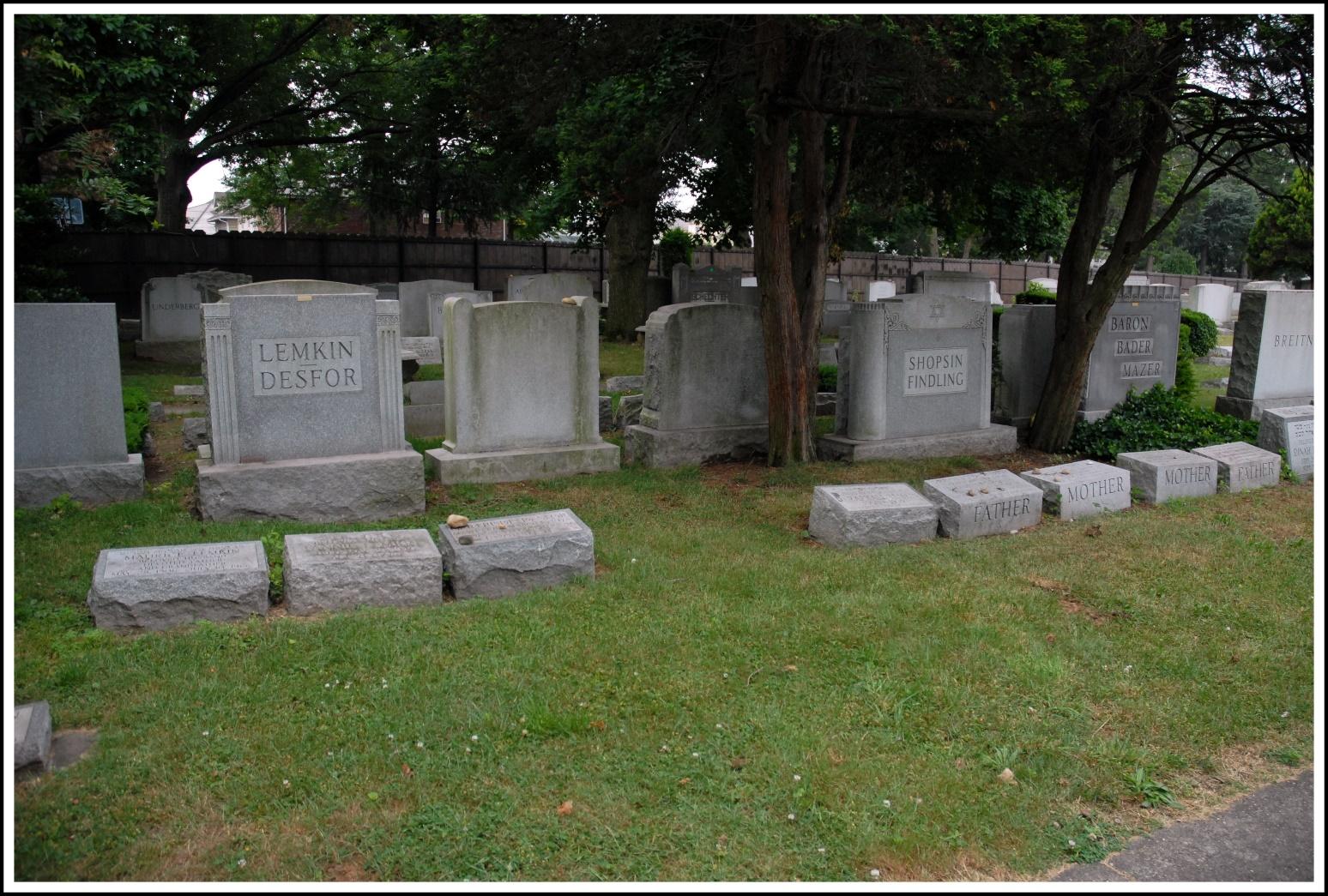

Fig. 13.

The Lemkin Plot,

Block 101, Lot ½ 238 & 239.

There are 10

individuals buried in the plot - 6 Lemkins, 2 Desfors, 2 others.

Even though

Raphael Lemkin was the first to be buried there, he was not one of the four

original owners of the Plot, but

a family member

was. (We thank Cedar Grove Cemetery Association for this information.)

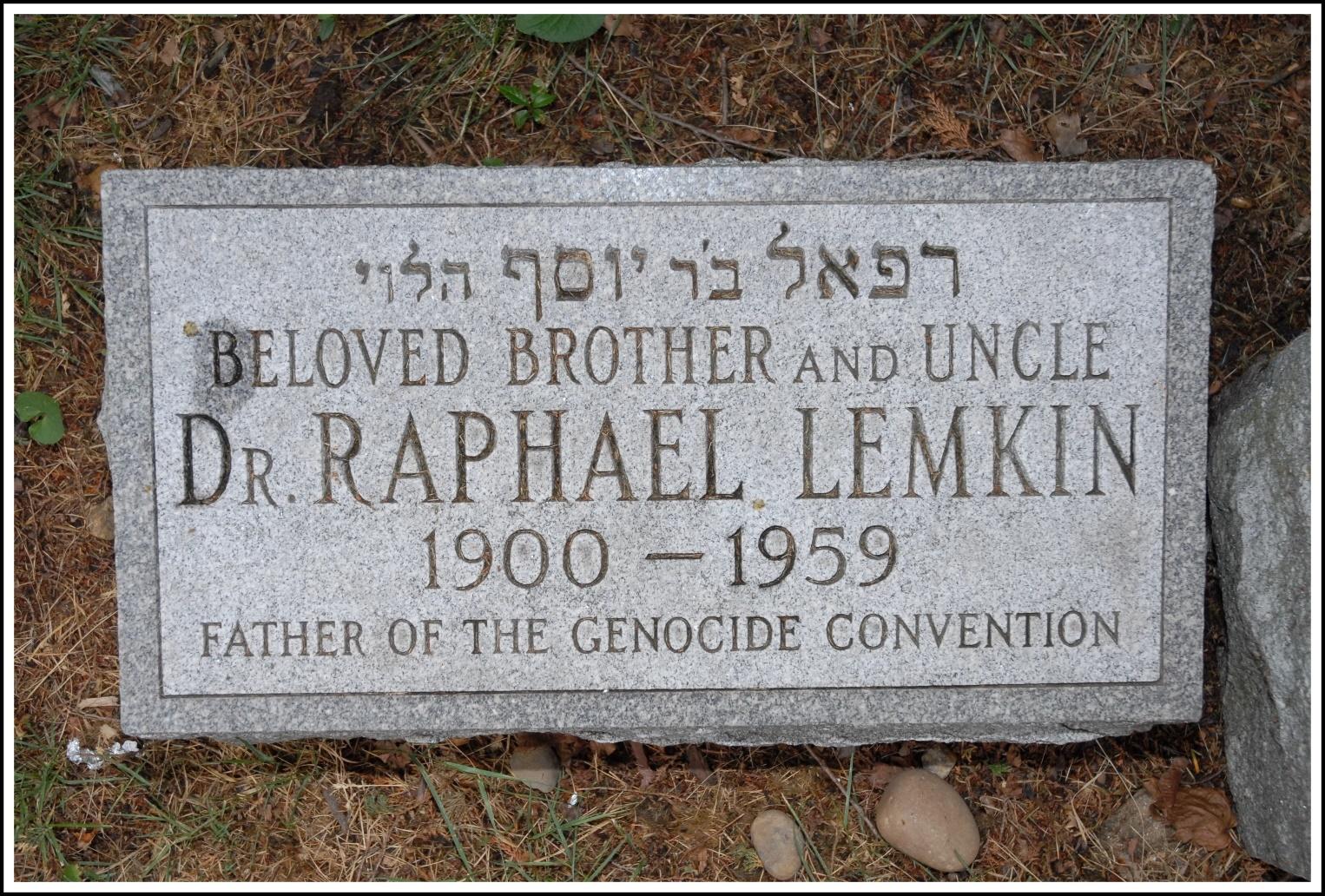

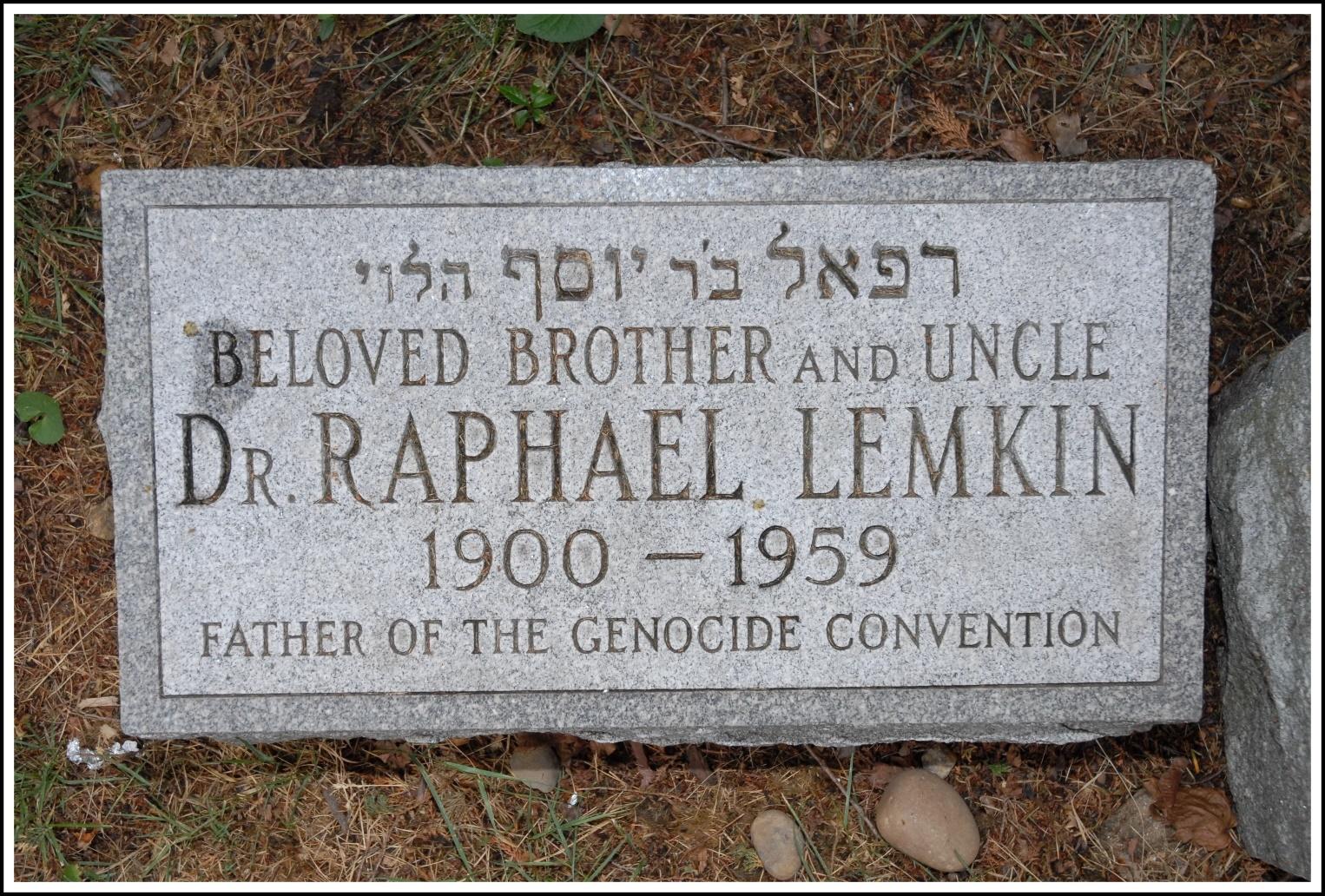

Fig. 14.

Fig. 15.

The Hebrew at

the top translates as “Raphael son of Yosef HaLevy.” Our thanks to Dr. Ann Kent Witztum for the translation from Hebrew.

Lemkin’s

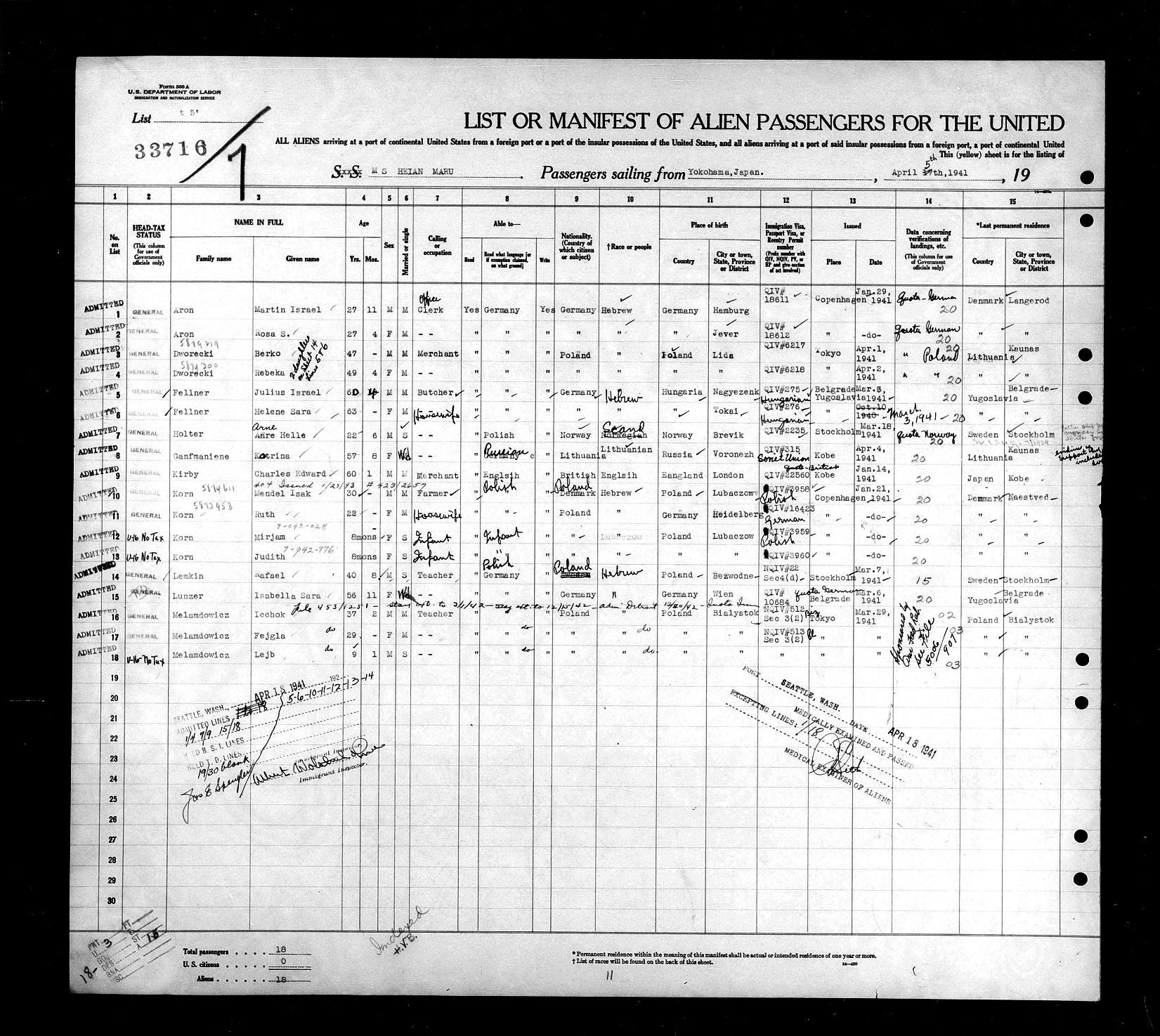

Immigration Into The United States

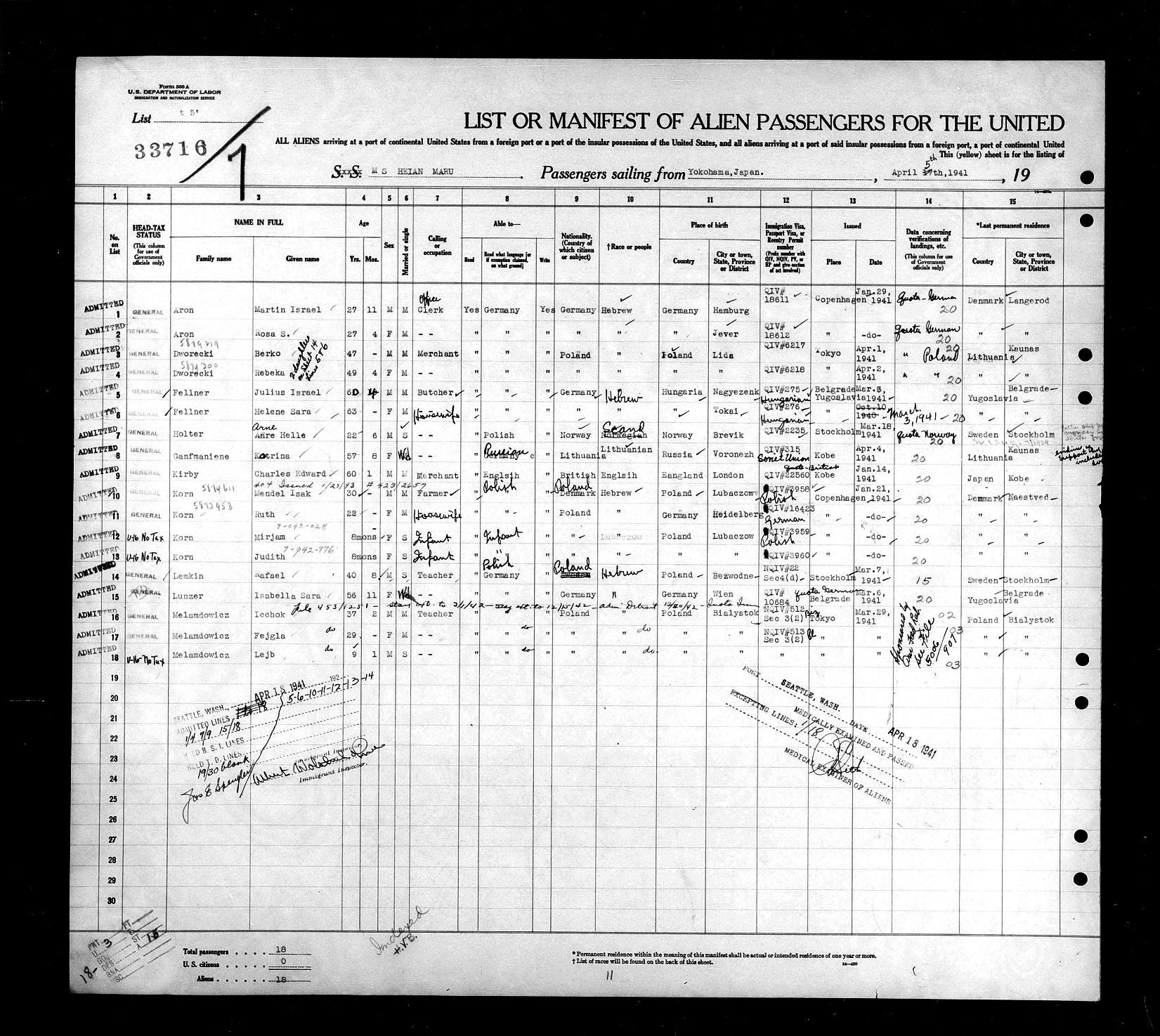

Lemkin’s immigration record detailing his

travel to the USA exists only on microfilm.

We were told by authorities in Seattle that originals no longer

exist. The ship manifest (Fig. 16a.)

shows that Lemkin left Yokohama, Japan on April 5, 1941, on the M.S. Hein Maru,

a Japanese ocean liner, and arrived in Seattle on April 18, 1941, where he was

medically examined at the port of entry and admitted.

Fig. 16a.

Copy of Ship

Manifest. (See Line 14 especially for Rafael Lemkin.)

Fig. 16b.

Cut-out showing

Line 14 from the Ship Manifest.

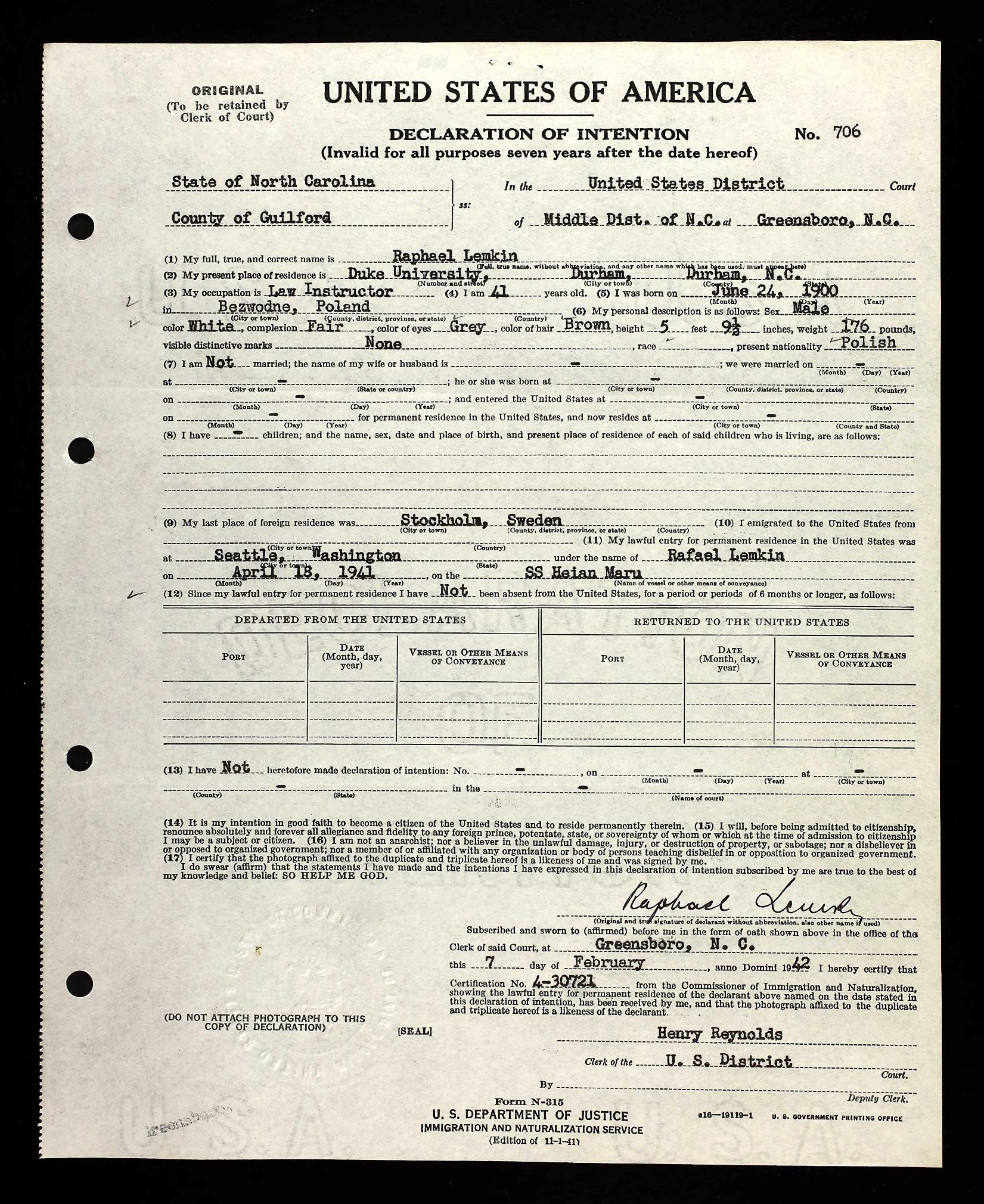

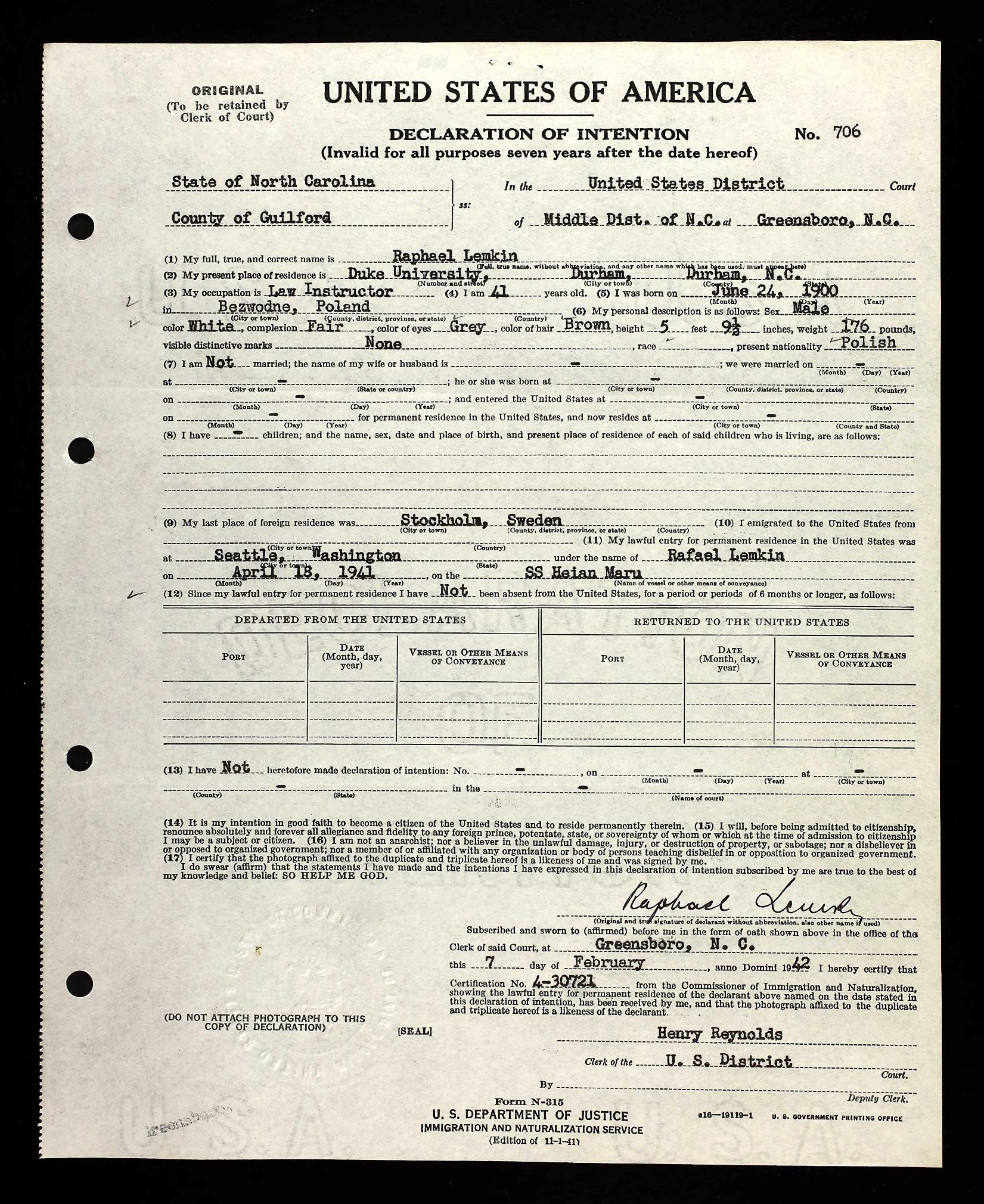

Fig. 17.

Raphael Lemkin’s

Declaration of Intention for American citizenship.

Note that

Lemkin’s first name has become ‘Americanized’ to Raphael.

We believe this is the first time it was formalized legally.

Lemkin And The

Armenians

Lemkin’s concern with the Armenians and

the crime that was inflicted on them by the Ottoman Turks under cover of World

War I and even earlier in the late 1890s and again in 1909, did not emanate

from a superficial interest gained later in his life. The Armenians of Turkey were very important

in the context of Lemkin’s idealistic struggles with framing appropriate legal

concepts on how one might punish perpetrators of such crimes. These concerns dated from 1921.

Lemkin relates that even as a youngster he

posed questions to his mother about the reasons for the persecutions of

Christians in the days of Emperor Nero’s Rome.

He had read about these dramatic torments and tortures in the novel Quo Vadis written by the immensely

popular Polish author Henryk Sienkiewicz.

Later in life, Raphael Lemkin described Quo Vadis as his favorite book when he

was a child. It appears that he was what

we would nowadays call a youngster with a potential for developing a deep

social conscience.

We learn from a brief but very telling

biographical sketch of Raphael Lemkin that “In 1921 he was profoundly upset by

a news item.” A young Armenian man named Soghomon Teilierian [the more usual and accurate anglicized spelling

of the surname is Telirian], had confronted the

Turkish Minister of the Interior, Talaat Pasha [Fig. 18], on the street near

his residence in Berlin, drawn a revolver, and killed him, shouting: “This is to avenge the death of my family!”[14].

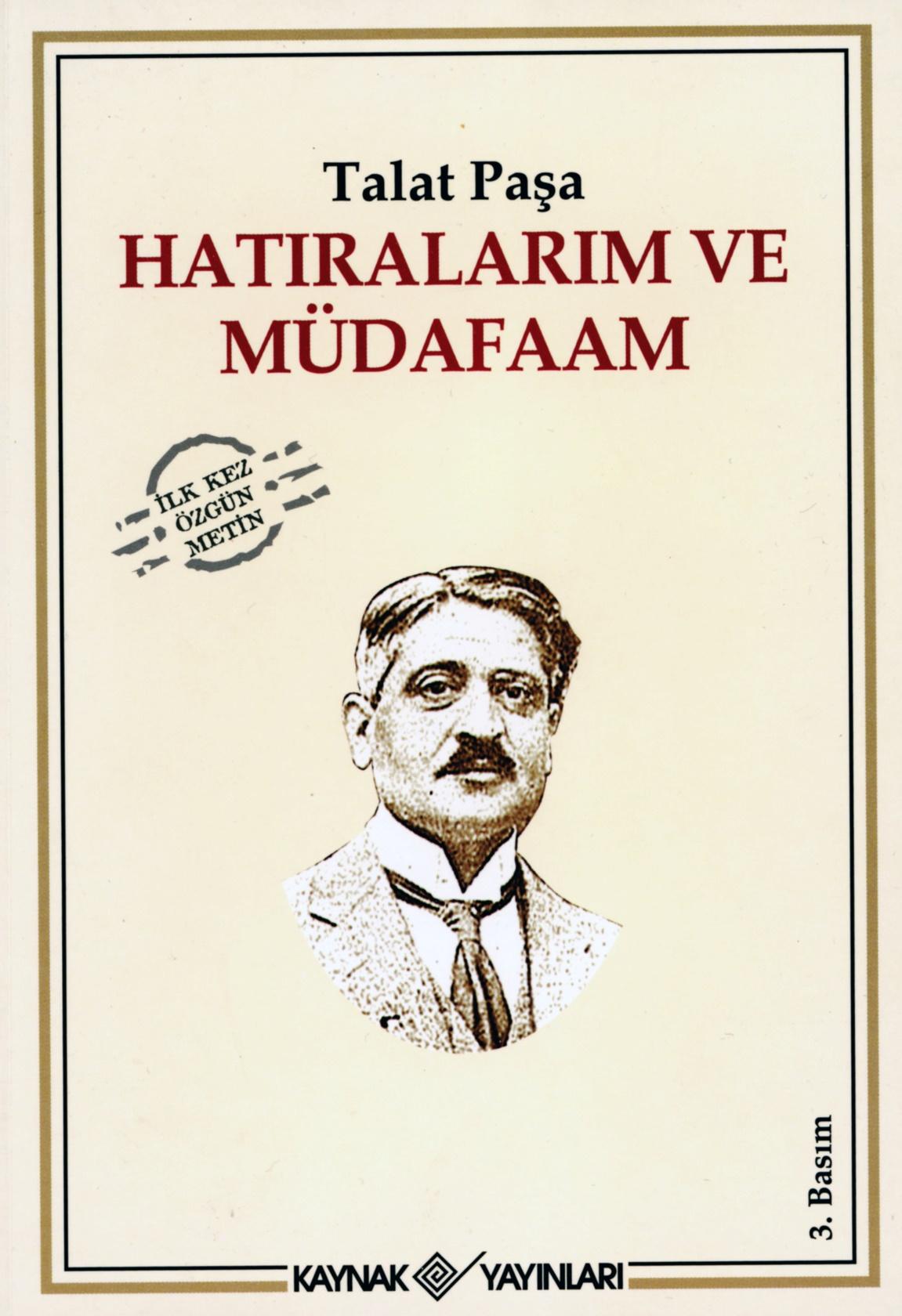

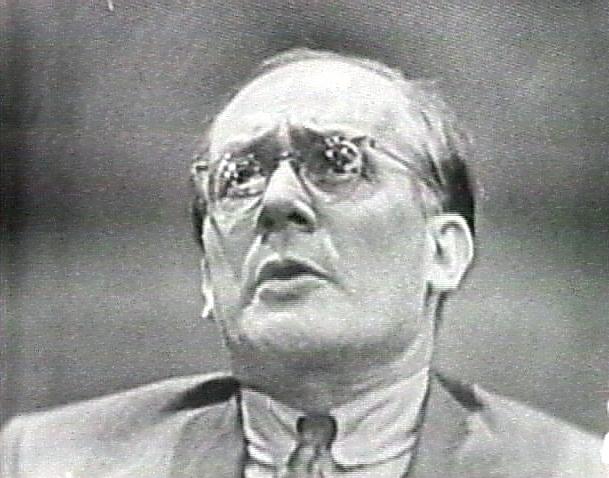

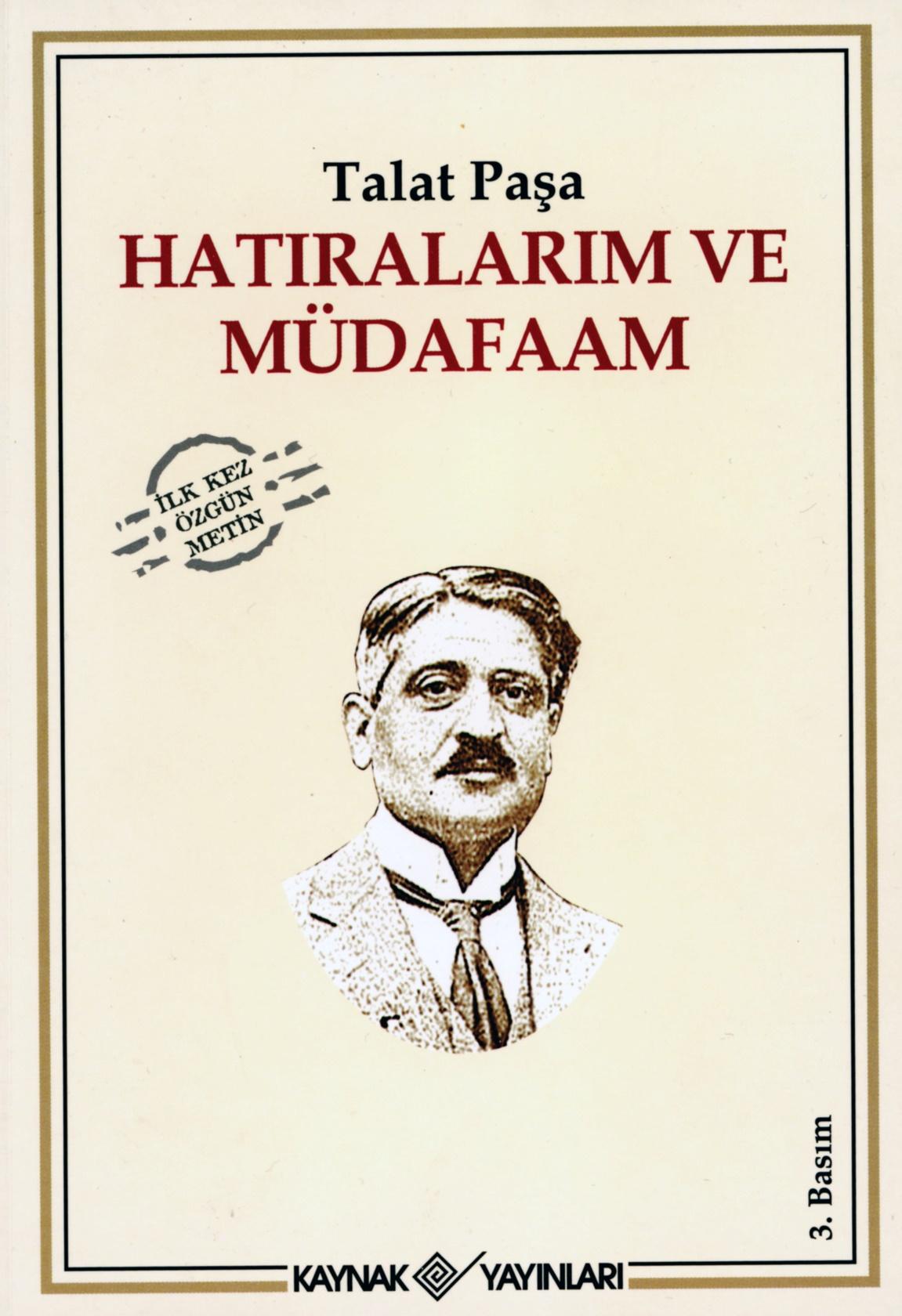

Fig. 18.

This late in life photo

of Talaat Pasha (1874-1921) shows the cover of a fairly recent volume (2006, Kaymak Yayinlari Press Istanbul]

with Talaat’s image entitled in Turkish that translates to English as “My Memories and My Defense.” Some plastic surgery is said to have been

performed on him and thus his eyes look a bit different from other photographs.

[15]

After

studying the assassination case of Talaat Pasha in greater detail, Raphael

Lemkin found that Tehlirian’s family had been part of

the more than 1,200,000 Armenians who had been eliminated starting in 1915 by

the Turks, when Talaat had been head of the Turkish police, and later when he

was Minister of the Interior.

Raphael Lemkin took what he saw as a problem to

one of his law professors at Lwów University.

“Did the Armenian try to

have the Turk arrested for the massacre?”

The professor shook his head. “There is no law under which he could be

arrested.” “But Talaat was responsible

for the death of those people,” Raphael retorted. His professor in the Law faculty responded: “Consider the case of a farmer who owns a

flock of chickens. He kills them and

this is his business. If you interfere,

you are trespassing.” Lemkin retorted:

“But the Armenians are not chickens.

Certainly –ˮ the professor continued: “You cannot interfere with the internal affairs of a nation without

infringing on that nation’s sovereignty.”

Raphael stood his ground. “It is a crime for Teilierian

(sic) to kill a man, but it is not a crime for his oppressor to kill more than

a million men? This is most inconsistent.”

The

final bit of advice offered to Lemkin was “You

are young and inexperienced, Lemkin, and tend to oversimplify. You should learn more about international

law.”

So Raphael entered law school at the University of Lwów.[16] For six years he searched ancient and modern

law to discover some written code against the crime of murdering national,

racial, and religious groups.[17]

All

this led to Lemkin

becoming even more preoccupied with the entire

problem. Figs. 19, 20, 21, and 22 are

images selected by us to tell some of the story connected with avenging the

deaths of Armenian genocide victims through assassination of Young Turk

leaders.

The

first Turkish target (Fig. 19a.) was Talaat Pasha, widely regarded as the

arch-assassin and prime initiator of the scheme to carry out the genocide.[18]

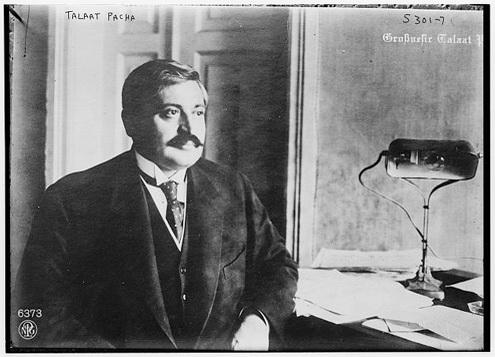

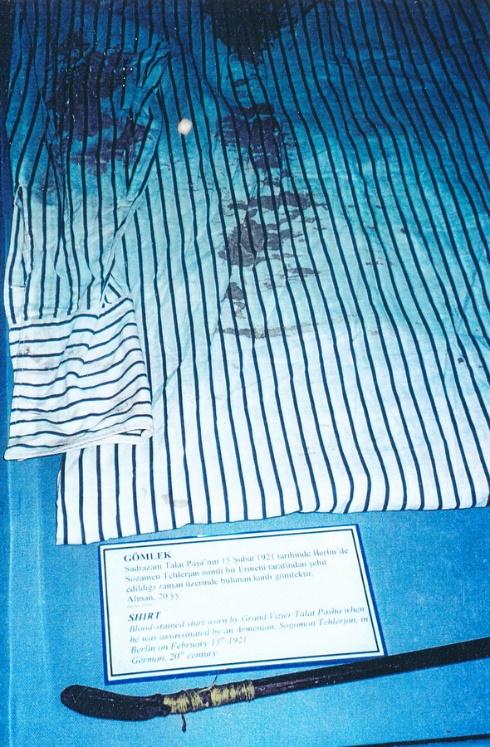

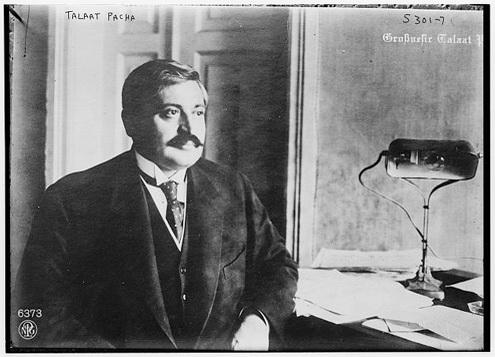

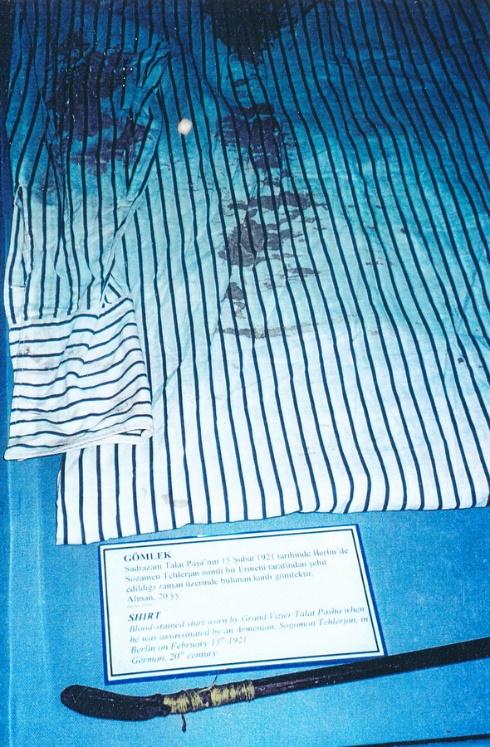

Fig. 19a. and 19b.

Fig. 19a. Talaat Pasha at

his ‘desk.’ From an undated photograph

in the Library of Congress, Bain News Service Collection [19];

Fig. 19b. The bloodied

shirt worn by Talaat when he was assassinated.

The shirt was in an Istanbul museum when this photograph was taken through a

glass case.[20]

The item has apparently

long been removed from public view.

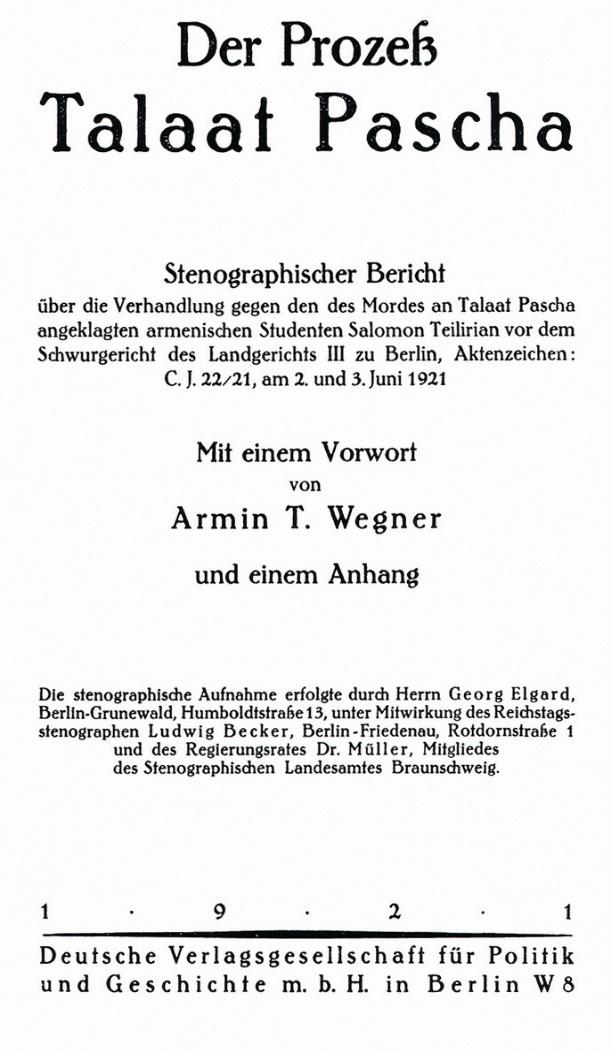

Fig. 20a. and Fig. 20b.

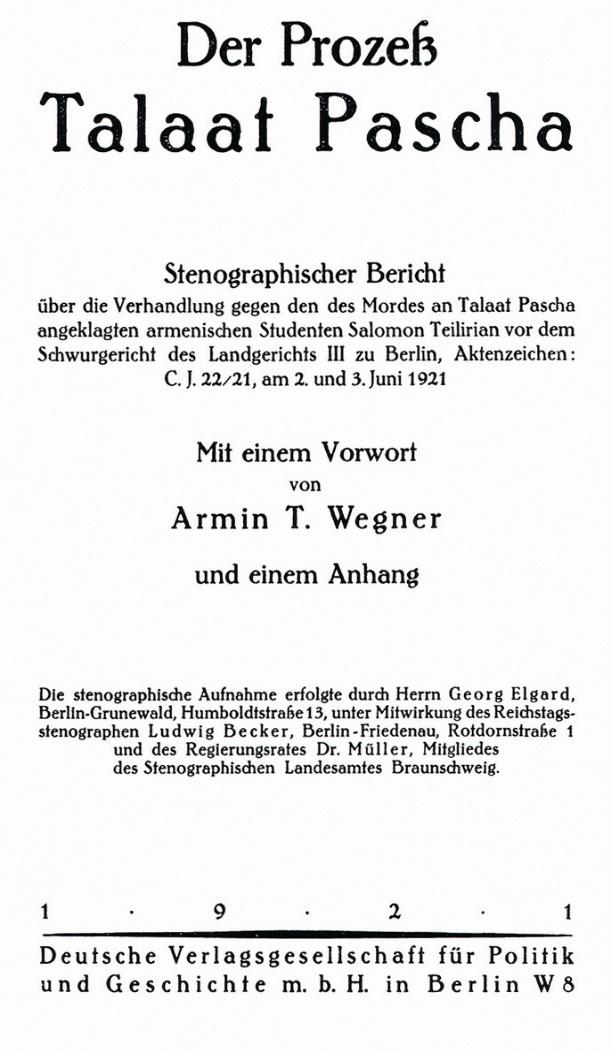

Fig. 20a. Title page of the German trial transcript. The booklet is some 132 pages long and

consists of the transcript of the two-day trial (Julian calendar June 22/21)

from 2 and 3 June 1921 in Berlin of the student accused of assassinating Talaat

Pasha Grand Vizier of the Ottoman Empire.

Armin T. Wegner wrote a preface and an appendix for the volume. Soghomon Teilirian (1896–1960), was the defendant. Teilirian, was

acquitted and deported virtually straightaway.

Fig. 20b. front page

article in the 4 June 1921 issue of the New

York Tribune reporting the acquittal of Salomon Teilirian

(sic) for Talaat’s assassination on the grounds of insanity.[21]

Fig. 21.

Dr. Behaeddin Sakir was yet another of the Young Turk criminals

assassinated for their roles in planning and implementing the Armenian

Genocide. Sakir was a member of the Young Turk Central Committee (in

Turkish, Ittihad ve Terakki Jemiyeti)

and a leader of the “Special Organization'' (in Turkish, Teşkilat-I Mahsusa) that had a major responsibility in organizing the

massacres.[22]

We

shall see in the course of our summary presentation here that even today one is

not sure by any means of the year, much less the exact date, and the precise

circumstances under which the invention of the word “genocide”

occurred. Whatever the particulars,

Raphael Lemkin was responsible for directly linking − several years before the

drafting of the Genocide Convention − his new word with what happened to

the Armenians. As a legal scholar and

practicing attorney Lemkin had struggled for many years with defining and

codifying the concept of punishment for the kinds of crimes committed by the

Turks. The small volume “Lemkin’s Dossier on the Armenian Genocide,” Lemkin, Raphael, 1900-1959, American Jewish

Historical Society, and Center for Armenian Remembrance. [Manuscript from

Raphael Lemkin's Collection, American Jewish Historical Society].

Glendale, Calif.: Center for Armenian Remembrance, 2008 provides as good as any

overview of Lemkin’s thoughts on the Armenians and their victimhood. [23]

Immediate Recognition Of

The Historical Importance Of

The UN Casebook XXI:

Genocide Film Footage

We had come upon a mention of this film on one

occasion in our reading and eventually learned that it included Raphael Lemkin

as one of the guests. Viewers are told

abundantly clearly in Lemkin’s own words that in his view what happened to the

Armenians was genocide. Locating the film was not an easy task, but

we believe it was worth all the effort we made in meeting the challenge.

With

that brief introduction we will now direct our attention to our work on

elaborating upon the film footage in a paper published some years ago by the

present writers, Taylor and Krikorian.

It showcased a full transcript of this unique 1949 television program

entitled “UN Casebook XXI:

Genocide.” It included a detailed

introduction so as to place this exceptional program in proper context.[24]

A

brief excerpt of that unique TV broadcast with its authoritative ‘notable’

guests presented leisurely before one’s eyes, was first shown in a powerful

documentary film produced and directed by Andrew Goldberg called “The Armenian Genocide” (2006).[25]

Like

many others, on 17 April 2006, we first saw on Channel 13, the PBS station

serving the greater New York City area, an hour-long documentary film

produced-for-TV entitled “The Armenian

Genocide.” It was written, produced and directed by Andrew Goldberg, founder and owner

of Two Cats Productions in New York

City. The documentary was put out in

association with Oregon Public Broadcasting.

We later learned that even before this documentary was shown publicly,

indeed some six weeks before the scheduled airdate, a complaint against the

anticipated broadcast had been lodged by one David Saltzman, Counsel to the Assembly of Turkish American Associations (ATTA).

In the end, the ATAA was given an opportunity to voice their reaction to

the documentary in the form of a post-program ‘roundtable’ discussion. We have read that ANCA (Armenian National

Committee of America) lobbied to have the ‘roundtable’ cancelled. The outcome allowed approximately 348

PBS-affiliate TV stations to show the program “The Armenian Genocide,” with or without the subsequent

‘roundtable.’ Apparently relatively few

stations ended up showing the post-program half-hour “roundtable” segment. The ‘roundtable’ discussion, advertised ahead

of time in a few places as “Armenian

Genocide: Exploring the Issues,” aired immediately post-program and was

skillfully moderated by noted National Public Radio commentator and journalist

Scott Simons.

The

New York-area broadcast that we ourselves watched did not include the follow-up

‘roundtable’ discussion/debate. A friend

in Austin, Texas sent us a copy of the program complete with the discussion

that was shown on their PBS station KLRU.

Professor Justin McCarthy of the University of Louisville, and Associate

Professor of History at Omer Turan University, then

at the Middle East Technical University in Ankara and now Professor at Bilgi

University in Istanbul, represented the Turkish Point of View. Professors Peter Balakian

of Colgate University and Taner Akçam,

then a visiting Professor at the University of Minnesota (later at Clark

University in Worcester, Massachusetts and now serving as Armenian Genocide

Research Director at the Promise Armenian Institute at UCLA in Los Angeles),

represented the perspective that what happened to the Armenians was a genocide.

The

marketing activities for the Goldberg film included the claim that the

documentary “featured never-before-seen footage.” This is a bit of an exaggeration of course

but there is indeed very important footage that few people had known about – at

least in the more modern context of genocide studies.[26]

Since

that time, brief excerpts from the same ‘original’ UN Casebook XXI film [27]

have been presented with increasing frequency on such modern communal platforms

as YouTube. In the majority of cases,

what is posted derives from the same ‘original.’ The excerpts from the broadcast selected for

showing inevitably give special emphasis to Raphael Lemkin, the originator of

the word “genocide,” and features him

talking about the Armenian massacres and discriminatory attitudes culminating

in Hitler’s Nazi actions.

Because

the well-intentioned and commendably promising ‘open [free]’ journal War Crimes, Genocide & Crimes against

Humanity above referenced was unfortunately very short-lived, we decided to

post the entire UN Casebook XXI

television program with our transcription as it was originally print

published. We added additional

commentary on our YouTube Conscience Films

site: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CXliPhsI530. Our decision to post the entire paper online

was primarily due to wanting to maintain and sustain access to our painstaking

work transcribing and publishing the broadcast in what had become an

essentially defunct journal. The YouTube

Posting allowed a decidedly fuller connection to this important broadcast along

with text added to enhance the broadcast.

The intended objective was to make students and researchers alike aware

of the many specifics.

Using

the contents of this United Nations

Casebook XXI film as a point of departure, we delved into the life and work

of Raphael Lemkin. In everything we read

he was featured both as a private individual and as a highly educated,

experienced jurist driven to introduce internationally recognized legislation

against this ‘crime of crimes.’ He was, one could say, truly obsessed with

this task.[28]

Much

of the 20,000 page plus Lemkin archive is now on

positive microfilm, and is available for research at various archives. Needless to say, the sheer volume presents challenges

(see Irvin-Erickson, Douglas, 2014). [29]

Lemkin

himself admitted on several occasions that he coined the word genocide as a result of hearing a radio

broadcast by Winston Churchill on 24 August 1941 wherein the British Prime

Minister spoke of a “crime without a

name.” [Gilbert, Martin 2007, Churchill and the

Jews: a lifelong friendship, Henry Holt & Co., New York pg. 186].

Many have taken to hearing this typically

Churchillian phrase and language to be the prime incentive for someone, indeed anyone, to rise up and provide a name

for the “crime without a name,” this

crime of crimes. Because of the

timeframe during which the comment was made by Churchill, it is assumed that

the genocide committed against European Jewry was foremost, if not the only

thing on his mind. It was not. Lemkin

had been struggling with the entire concept for years! [30]

Lemkin certainly listened to Churchill’s

speech, and we might speculate that he even hung on every word.

As mentioned earlier, prior to coming to

America, Lemkin lived in neutral Sweden where he closely monitored German

occupation policies in his native Poland where his parents and family remained,

as well as policies in neighboring Norway and all of occupied Europe. Swedish travelers coming and going from

Stockholm helped Lemkin assemble a collection of publicly available German

occupation laws and decrees, which Lemkin analyzed in an effort to understand

the pattern of the policies being implemented in Hitler's New Order in Europe.

From these

documents, Lemkin concluded that alongside the traditional war of armies,

Germany was engaged in a war against peoples.

To Lemkin the collection of occupation decrees demonstrated a Nazi

policy aimed at nothing less than a demographic restructuring of the European

population. Following the design set out

in Hitler’s Mein Kampf

published in 1925, some groups would be encouraged to thrive, others to

decline through depopulation over time, and others would be targeted for

destruction.

In Lemkin's

native Poland, for example, the German occupiers had created a racial hierarchy

in which so-called and in reality, scientifically indefensible "Aryan" peoples (ethnic German

Volkesdeutsche)

received the full food rations and were encouraged to have more children, even

out of wedlock. Ethnic Poles and other

Slavic groups were forcefully subjugated, their leadership and intellectuals

sent to concentration camps or killed outright.

The remainder of the Slavic population was to survive on minimal rations

only to the extent that their labor was needed by the dominant "Aryan" population group. The Jewish population, consisting of two

million people including Lemkin's own family, was being exterminated. Extermination was accomplished by forcibly

resettling the population in ghettos or camps where people died rapidly through

slave labor, starvation, exposure and contagious

diseases such as typhus - living conditions designed to cause their destruction

through attrition.[31]

The Polish Institute of

International Affairs convened a conference on 18-19 September 2008 in Warsaw on the 60th

anniversary of the adoption of the Genocide

Convention. The conference was aimed

at appreciating the life and elaborating on perpetuating the legacy of the work

of Raphael Lemkin.[32]

Professor

Ryszard Szawłowski,

a contributor to that volume, has ventured to say that “the term genocide was probably already conceived by Lemkin in the

first half of 1943, if not somewhat earlier” (Szawłowski,

2005 pg. 120.) [Endnote 6 has the exact

citation.]

Given

the apparent importance for many of the word “genocide” in the overall narrative, it seems imperative to

understand the neologism - the new word - as coined by Raphael Lemkin in as

much detail as possible. (Some academics

have complained that he used unorthodox mixing of Greek and Latin in coining

the single word, genocide.) Such people would have probably complained

that Lemkin did not walk on water!

Towards this end it becomes clear why we have thought it most necessary

to delve into this issue in as much detail as we can.

‘Parenthetically,’ rather we should say

‘non-parenthetically,’ we would emphasize that the United Nations Genocide Convention has been reproduced in a great

many places on the Internet. That does

not mean, of course, that all or any of those who use the words have taken

advantage of the opportunity to read them, much less study them. Nevertheless, to facilitate the possibility

of changing that situation, we provide the following URL from the United

Nations Dag Hammarskjöld Library website.

It provides direct access to the full UN document in English and

French.

UN Digital Library E/794:

https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/604195?In-en

[Full original report]

[1 page Corrigendum to the original

report]at /794/Corr.1

https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/604196?ln=en

Sadly,

Raphael Lemkin’s original concept and desired definition of “genocide” did not fully prevail in the

final Genocide Convention that he

‘fathered’ and promoted so energetically, but he did adhere faithfully to his

original concepts throughout his relatively short life, even though he

recognized and even admitted that some compromises would have to be acceded to.

We

will refrain from comparing and contrasting the ‘draft(s)’ and the final

version of the Convention.[33]

We

provide in Endnote [34]

part of the account written by Raphael Lemkin in the Preface of his book “Axis

Rule in Occupied Europe” as it relates to genocide. These pages are

the very first place where the word “genocide”

appeared in print (Lemkin, 1944 pgs. xi-xii).

We’ll see later that Raphael Lemkin was even

able, when the occasion arose, to put on in public a rather positive if not

bright face concerning things that he knew to be severely flawed. He had done all that was humanly possible,

and he was forced to believe in compromise.

However, the fact that his own adopted country, the U.S.A., could not be

induced to ratify the Convention troubled and hurt him deeply. It is worth repeating that he died in

complete poverty − a morose, disheartened, broken and broke man. One could say that it was merciful that he

died suddenly of a heart attack.

“The Armenian Genocide” –

A Documentary Film Broadcast On PBS

It was both annoying and disappointing that we

had to spend so much time tracking down a recording of the Casebook XXI

program. We knew one had to exist since

we had seen the excerpt from it in Goldberg’s film but requests on our part

went unanswered. Happily, it was eventually found at the National Jewish

Archives (NJA) on 92nd Street and 5th Avenue in

Manhattan. This was made possible through the generous help of Ms. Leshu Torchin, then a Doctoral

Candidate at New York University. Dr. Torchin (earned her Ph.D. back in 2007) has made

significant contributions to visual communications as they relate to the

Armenian and other genocides (see e.g. (Torchin

2007).[35] We would have been at a total loss had we not

been told about Jeffrey Shandler’s book “While America Watches” (Shandler, 1999). We

bring this up since what could have been an easy task turned out to be a major

project until Ms. Torchin put us on the right track.

The

film footage featuring Raphael Lemkin and Quincy Howe used by Andrew Goldberg’s

“Two Cats Productions,” and since

then by the proverbial ‘everybody and his cousin’ derives from a 13 February

1949 joint CBS/United Nations Casebook

XXI broadcast in New York City.[36]

Much

of the material written or stated by Raphael Lemkin in connection with the

Armenians and the Armenian Genocide, has today become fairly well-known – at

least in a very general way—and at least by Armenians and their

sympathizers.

In

fact, a popular exhibit at the Jewish Historical Society Center for Jewish

History, ran an award-winning program from Nov. 15, 2009, to May 2, 2010. The name of the exhibit was “Letters of Conscience: Raphael Lemkin and

the Quest to End Genocide.” It

started off by saying “Almost 90 years

ago, a young student in Poland became intrigued – and deeply troubled – about

the case of an Armenian youth accused of murdering the Turkish official

responsible for the 1915 genocide of the Armenian community in the Ottoman

Empire.” That clearcut statement

reached quite a few museum goers. Only a

very short notice of the exhibit was retained online.

Over

the years, a number of Raphael Lemkin’s hitherto unpublished papers and

manuscripts have appeared in print. Of

special interest are Lemkin’s essays by Rabbi Jacobs, which have been written

as well on the nature of exactly what Lemkin had to say about the Armenian

Genocide.[37] These have been very important in bringing

Lemkin to the attention of many Armenians in considerably greater detail, as

well as to those purportedly interested in comparative genocide studies.

Nevertheless,

despite the printed word, be it in articles or books, seeing Lemkin on film has

brought his feelings on what had happened to the Armenians into full relief and

in an unequalled fashion. There is

nothing like seeing him talk in a straightforward way and hearing “genocide” and “Armenians” right from his own lips! Raphael Lemkin talking about the Armenians

and the genocide perpetrated against them, provides us with an important

symbolic image. See Fig. 22a. and 22b. below, clipped

from “UN Casebook XXI: Genocide.”

Fig. 22a. and Fig. 22b.

Fig. 22a. Raphael Lemkin

with moderator Quincy Howe;

Fig 22b. Raphael Lemkin

talking about the Armenian Genocide.

Still photographs

captured from UN Casebook XXI: Genocide – at approximately 17 minutes.

There

can be little doubt that the Raphael Lemkin segment of Andrew Goldberg’s

documentary perked up many a viewer’s ears and widened many a viewer’s

eyes. Goodness! “Armenian Genocide” voiced

by the man who coined the word!

Professor Peter Balakian made a special point

in the post-program ‘roundtable’ discussion of Andrew Goldberg’s documentary

that “Raphael Lemkin, the man who coined

the word genocide spoke in no uncertain terms about the genocide against the

Armenians.”[38]

The

clear-cut pronouncement by Raphael Lemkin was understandably very much welcomed

by the American community with Armenian roots or connections and their

supporters. Here was still another piece

of unambiguous evidence for all the world to see, that there is full

justification for the position that what happened to the Armenians under cover

of World War I qualifies to be called a genocide. Statements often used by Turks when referring

to what happened to the Armenians like “an issue which its proponents call the

Armenian Genocide” have no place in our opinion in honest discussions and are

long past beyond insulting.

The

upshot is this. There was initially, and

continues to be, enthusiastic reception of Goldberg’s film “The Armenian Genocide.” It

is a very well-executed film from a number of perspectives. But for many, the appearance of Raphael

Lemkin was a particularly noteworthy feature of the film. Since that initial screening, a point has

been made by many for showing Raphael Lemkin talking about the Armenian

Genocide for commemorative reasons, for purposes of affirmation of the Armenian

Genocide and for what might be, for lack of a better term, pure and simple

congratulatory reasons. Journalist Harut

Sassounian in his California Courier wrote

a good article on the documentary being shown on the occasion of the

presentation of the Lemkin Prize to Peter Balakian in

2005. This prize, a biennial recognition

made by the Institute for the Study of Genocide, is given in recognition of the

best non-fiction book − excluding memoirs, poetry, and drama – in the previous

two years.[39] Showing Lemkin on film on such an occasion

seems very appropriate indeed.

There

can be little doubt that locating the film featuring “Quincy Howe, the CBS News

Commentator” and “Raphael Lemkin,” by Two Cats and its subsequent integration

into “The Armenian Genocide” documentary was an important accomplishment.

However,

and not surprisingly, because of the imposed format for presenting the clip,

and its necessary brevity in the context of Goldberg’s documentary, it is fair

to say that there are many unjustified assumptions, even misconceptions,

concerning this ‘Lemkin film footage’ that have since arisen. This is mostly due to people not having the

means to look into it, or equally accurately, any interest in analyzing it in

any depth. Many of these issues persist

on the Internet and in the traditional print media alike. For example, the exact origin of the ‘Lemkin

genocide film footage’ is never provided.

Our paper published in War Crimes, Genocide & Crimes against Humanity appears

to a be “a first” in that regard.

Unavailability of a complete transcript of the 1949 broadcast, the

extant film of it a rarity unto itself, up until now limited any study.

One

can see that having the opportunity to examine and study the ‘original’ film

footage of the broadcast, before

editing and integration into the “The Armenian Genocide” documentary, revealed

some points that would have been missed.

Few would disagree that no study of history can

remain definitive for any great length of time, and it follows that mostly everything

can profit by re-examination. ‘Data

mining,’ a term normally used in computer science but also used in other

fields, that is the attempt to glean as much information by repetitive analysis

from different perspectives, can indeed yield new information and open up new

avenues for further study. Certainly,

there is a lot of room for more careful analysis and fresh research.

What Motivated Raphael

Lemkin To Coin The Word Genocide?

Like everything else, this is not as easy to

answer in as concise a way as one should like.

There are at least a few places that we know of wherein Raphael Lemkin

mentions how he felt obliged to come up with a name that adequately reflected

what the crime was all about. But we

want to emphasize that in the course of delving further into the matter, we

have come across more than a few inconsistencies. We shall attempt to develop this situation in

a sort of sequence and draw attention to a few of them.

Several

years ago, we found a document of considerable interest to us while going

through Lemkin materials (on microfilm; with hard copies at the New York Public

Library Manuscripts and Archives Division) bearing the caption “Text of statement by Dr. Raphael Lemkin at

Testimonial Luncheon in his honor by New York Region of the American Jewish

Congress at the Hotel Pierre, Thursday, January 18th”

[1951]. If we read the part of the text

that is relevant to us here, there are a number of things that enable one to

gain a better perspective vis à vis Lemkin and the Armenians. First of all, Lemkin has said that he was

moved to come up with a name for “a crime

without a name” – a phrase used by British Prime Minister Winston Churchill

in a speech on BBC radio on 24 August 1941.

We have decided to include the full text. It is very interesting, and we believe you

will agree that it is useful for us to have included it despite its length.

According to the transcript of the address made before the audience at the American

Jewish Congress testimonial luncheon in his honor, Lemkin related:

“At the beginning of the

last war, I heard a radio broadcast by Winston Churchill. He was denouncing the Nazi atrocities, and he

said: “The Nazis commit a crime without a

name.” This statement struck my

imagination. For some 18 years I had

been working for an international law which would prohibit the destruction of

nations, races and religious groups. I had submitted a draft of such a law to a

League of Nations Conference in 1933. It

was tabled because I was told that such a crime very seldom occurs, and it is

not worthwhile to make a special law for such rare occasions.”

One

will notice that Raphael Lemkin made no mention on the UN Casebook XXI broadcast about the victimization of the Greeks of

the Ottoman Empire. The probable reason

was that experienced moderator Quincy Howe had established a strict timetable

to follow and may well have thought that encouraging Lemkin to include it in his

interview and commentary might detract from the intended general focus. It has only been relatively recently that the

details of the Ottoman Greek genocide have been publicized broadly and promoted

for educational use in understanding the genocide process in general.[40]

There

is no reason to adopt the notion that the Armenian Genocide never occurred, see

e.g. the brazen stances taken by Turkish spokespeople

in Pea Holmquist’s pioneer film “Back to

Ararat” 2015 (ISBN9782399243176).

These liars are quite unconvincing, and their body language inevitably

betrays them.

The defense made by the Turkish Government

regarding the Armenian massacres reminds one very much of a popular story about

Jews that was circulated at the German Reichstag. Two Jewish women brought their dispute before

an old rabbi about a kettle which the plaintiff could not get back from the

defendant. The defendant said, first she

knew of no such kettle, second she had returned it

long ago, and third, the kettle was not worth speaking about since it was

broken.

The Turkish Government claims: first, there were

no such things as Armenian massacres; second, the massacres had in every

place only a local and unofficial character, no orders having been issued by

the Government; and third, the Government orders were issued only in

self-defense and had the approval of their enlightened Ally, the Germans. To which the innocent Germans retort that

they had no share whatever in the scheme and they were mere horrified powerless

lookers on.

Officiously the Germans put the whole blame of

the Armenian massacre on the Turkish Government and wanted to shake from

themselves any parcel of participation or responsibility in the Crime. A good deal of propaganda has been done in

this respect, the most important piece of work to our knowledge being the painstaking document full of American and German

statements privately printed and circulated as strictly Confidential by Dr.

Lepsius, head of the German Missionary works [Deutsche Orient Mission]. It may be granted that Dr. Lepsius is fairly

sincere in his indignation to see malevolent people charging the Germans with

participation in the massacres of 650,000 Christians by the hands of the

Heathen. He brings good proof of the

Massacre being planned quite carefully by the Central Government in

Constantinople. He goes even further and

discloses that the Armenian massacres were only a “coup d’essai” [a first

attempt] though a “coup de maître” [masterstroke] and were the so- called

civilized World to accept it with not too loud displeasure, the Greeks, and

other Christians and the Jews would have followed.

But just like all the most honest and sincere

German productions, Dr. Lepsius’ work has to be taken cum grano

salis [with a grain of salt]. He fully admits the Turkish cruelty, the

Turkish deep-laid plot, and supplements proof and witnesses to the

facts, that far we may follow him. His

whitewashing of the German Government involvement may be argued. It would probably be unfair to suspect Dr.

Lepsius of having written his apologia by order, but like all law-abiding

Germans he submitted his apologia to the Authorities. Dr. Bethmann-Hollweg has allowed one of his

letters to be published in the “Introduction", a letter in which he

assures he will do his Christian duty “in the future", by straining all

means to prevent a repetition of the disgraceful massacres. Therefore, the document takes on a wholly,

official character which makes it disingenuous.

If the German Government had reasons to approve (without approving) the

massacres, they have probably not found it fit to take Dr. Lepsius into their

confidence.

Lepsius had spoken to dozens of German officers,

physicians, etc., who had been in the thick of the massacres, and this is what

he found out. Each and every German was

individually horrified at what he had witnessed. Trained with a superstitious respect of

property, order, etc., a German cannot be expected to look in cold blood

placidly at the robbery, massacres, etc.

To say, therefore, that the Germans were leading the massacres, or even

taking a direct hand in them, as it has often been repeated, is doing them a

wrong or at least advancing things which can never be proved. The Germans will always be able to prove by

testimonials, diaries, protocols, etc. that in each case their soul revolted.

But slaves to discipline, and having given up

every individual thought or movement, the Germans who were ordered to duty in

the massacre-area, saw the outrage, and felt indignant, but made no move to

stop it. That is certainly from a higher

moral ground participation, even if not direct.

Officially the German Government has not entirely

repudiated the recognition of the supposed necessity of the massacres by

the Turks. Official inquiries have been

made, and no smaller man than Ernst Basserman, whose

words carry weight as the leader of the National

Liberals, and member of the Reichstag,

had openly and un-mistakenly given the Turkish Government absolution for what

they did - invoking of course the higher Raison d’ Etat. In a word, German official approval was not

entirely withheld from the Turks.

The German mentality is even today always

puzzling. The Armenian Question was a safe question to tackle with official

Germans. Pastor Lepsius never failed to

bring up the topic of the massacres when talking with the officials and

military populace, so he had plenty of opportunity to hear hundreds of stories

proving the cruelty and the useless and shameless barbarity of the Turks. But just about every clean minded person

would certainly shrink at the idea of making any profit from the situation the

Armenians were in. Not so the

Germans. They made bargains. It would be unfair to say they robbed the

Armenians - those poor souls being compelled to abandon their things without compensation, or give them away for mere

consideration. The Germans took

advantage of conditions and bought carpets, jewelry, trinkets for a tenth of

their real value. Germany became the

richest country in ‘oriental’ carpets.

Now, one more thing has to be considered. For some time, the Germans realized for

political reasons it would be good to colonize the Kilimanjaro, in arid,

relatively un-fertile East Africa, and other colonies which are not a

white-man's Country blessed by favorable geographical, climatical, agricultural

and mineral conditions. More than 75

years ago Von Moltke pointed to that area as a future colonization ground for

the Germans, and more and more Germans agreed.

Looking at it from this light, no one who knows

anything about Germans and the law, and the crooked way they can go to get

their high ambitions realized, would deny their methods which became divine

missions. They would not hesitate to wipe out the thriftiest element in these

countries. It would not have displeased or hurt German politics. And would not the Germans, themselves who

were better fed at that time, and in more boisterous spirits than today ask the

question: A crime? Answer: That is arguable, but it is not bad, far sighted German

Real Politik.

The

bare fact remains that the Armenian massacres were carefully planned acts by

the Turks, and the Germans will certainly be made to share the odium of this

forever.”[41]

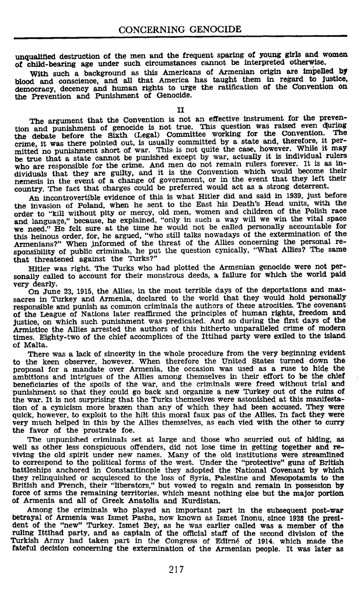

A Fair Amount Has Been

Said About How The Armenians Used The Word “Genocide”

As Far Back As 1945

We believe that the best way to cover all the

points of greatest importance, and the context in which these important points

were made, is to reproduce all the pages from an article that we think is very

telling. While it calls for the support

of the Genocide Convention, it makes

it clear that one should not avoid calling “a spade a spade.” It also makes clear that it did not endorse

the ‘blind endorsement’ given by the Armenian Revolutionary Foundation of the Convention in its Hairenik publication. Clearly, there had to be some nuance to it.

Whether

one agrees or disagrees with the viewpoint taken in the Armenian Affairs

article, it underscores the view that some of the Armenians saw that the

Genocide Convention was not going to be a panacea and inevitably provide a

means of punishing those who carried out such crimes. The Armenians had been there “before.” An

elderly Armenian immigrant and survivor once told a youthful ADK that “Menk ahl khelk oonick!” [We too have brains!] Indeed. How right he was.

Fig. 23.

Fig. 24.

Fig. 25.

Fig. 26.

Fig. 27.

Fig. 28.

Fig. 29.

Fig. 30.

What Do ‘The Armenians’

Want From ‘The Turks’?

Non-Armenian friends, both in the U.S.A. and

abroad, have often asked us “What do the

Armenians want from the Turks?” “Why

is it so important that the word “genocide”

enter into any consideration of the ongoing antagonisms between the ‘Armenians’

and ‘Turks’?” Those who advocate the ‘Turkish Point of View’ − that there was no genocide − claim

not to have a clue as to why the use of the word “genocide” is insisted upon in

connection with the ‘Armenian Point of

View’. After all, are words like

“tragedy,” “catastrophe,” “disaster” etc. not adequate to describe what

happened? [42] To be brief and to the point, for us writing

this essay and apparently many others, “No!”

It not only does dishonor to the truth, and violence to the facts, but

adds insult to injury to those who were murdered and lost their lives through genocide.[43] It should also be underscored that it has

long been recognized by non-Armenians that “The

Armenians…whose outstanding characteristic is stubborn determination of

purpose…” (see for example Corbyn 1932 pg. 600). Stubborn or tenacious or perseverant? [44]

More

often than not, many will have a very personal answer to the question, “What do the Armenians want from the Turks?” For example, psychologists and psychiatrists

have given the transmittal of pain and its many permutations from generation to

generation, the designation “transgenerational

trauma.” There are few Armenian families anywhere who

were not touched directly by the Genocide. One author, we forget who, said that this

lingering or residual trauma prevents genocide

from “receding into the cold storage of

history” – presumably implying that is where memories of genocide

belong? Be that as it may, there should

be no doubt that what has come to be tritely and casually (and offensively to

us) referred to as the “G” word (sometimes with a lower case “g”) seems to

encapsulate for many descendants of Armenian

Genocide survivors, the ‘all’ and ‘end-all’ of what happened at the hands

of the Young Turks and their government beginning in 1915. (We will only mention here in passing the

Hamidian massacres of the 1890s, and the Cilician massacres of 1909.)

A

very important part of the answer to the question “What do the Armenians want?” is understandably connected with

preserving memory. Some have described

this need to remember, as nothing less than a sort of moral as well as

emotional pact between the dead and the living.

It

has always struck us as a sign of a rather significant ‘disconnect’, when we

hear or read that the Armenian Genocide

is ‘a’ or ‘the’ ‘forgotten’ or ‘unremembered’

etc. genocide. It is certainly not forgotten by Armenians or

many others. Neither is it forgotten by

the Turkish government. This reminder of

the facts constantly shows up as a thorn in the side of ‘Turks’, who are

spending immense amounts of money denying the Armenian Genocide. The

popular TV program “60 Minutes” first aired on 28 February 2010, a segment

entitled “Battle over history” by

Michael H. Gavshon and Drew Margatten. It has been estimated that some 13.4 million

people worldwide watched “60 Minutes” each week. It has been in the Nielsen ratings top ten

for quite a few years. One can therefore

be reasonably certain that many know about the Armenian Genocide. But the

message has to be repeatedly repeated since so much gets erased, supplanted, or

superseded with other priorities on the internet.

It is certainly true, however, that since much of

the world is living day by day, there is no doubt that most non-Armenians have

long since forgotten about the phrase ‘the

starving Armenians.’ Sad to say there have been extreme elements

among the Armenians, who out of frustration, resorted to terrorism and violence

against Turkish diplomats in the early 1980s, to bring attention to what they

called the Armenian Cause and

political recognition of the Armenian

Genocide. Happily, this strategy for

airing grievances and achieving essentially impossible dreams was abandoned,

but only after a number of tragedies.

Curiously or not, it has been admitted that this senseless violence did

bring attention, more precisely notoriety, to the ‘forgotten’ Armenian Genocide. [45]

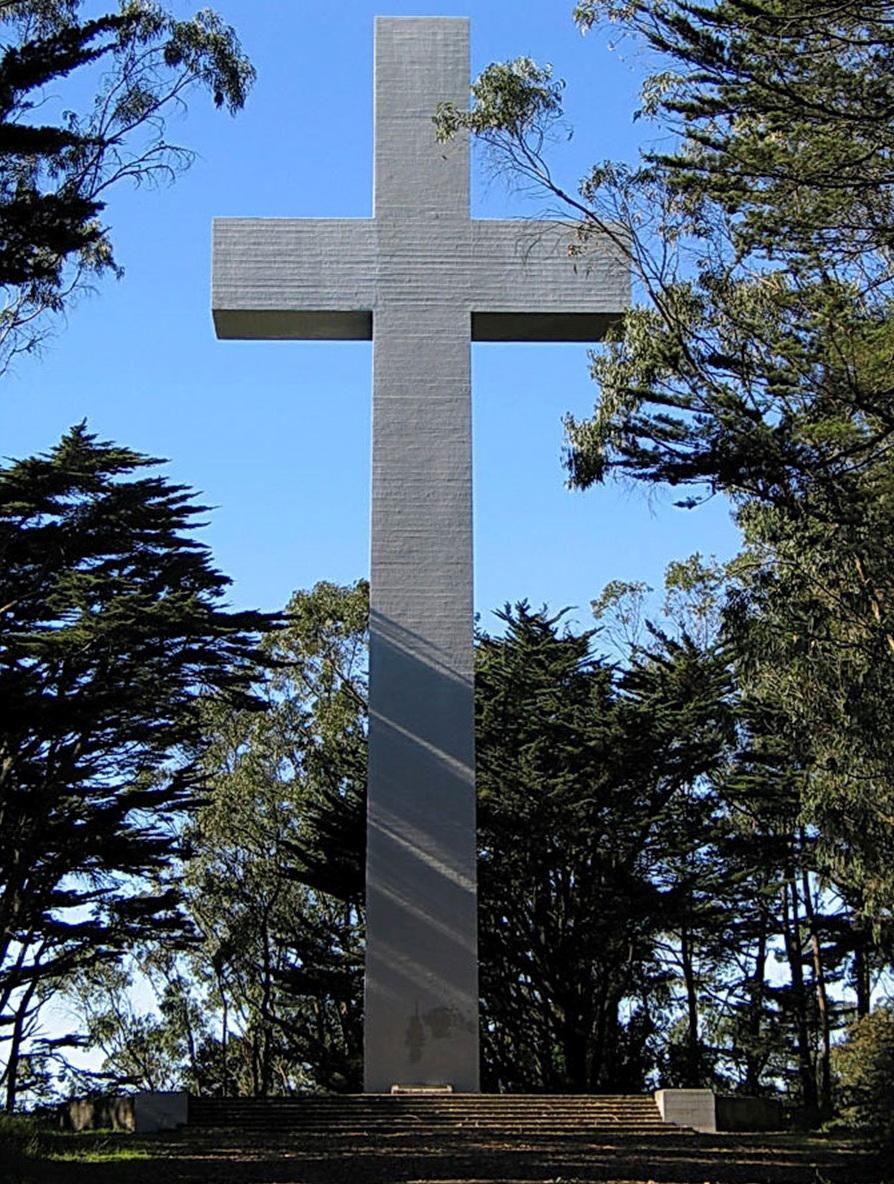

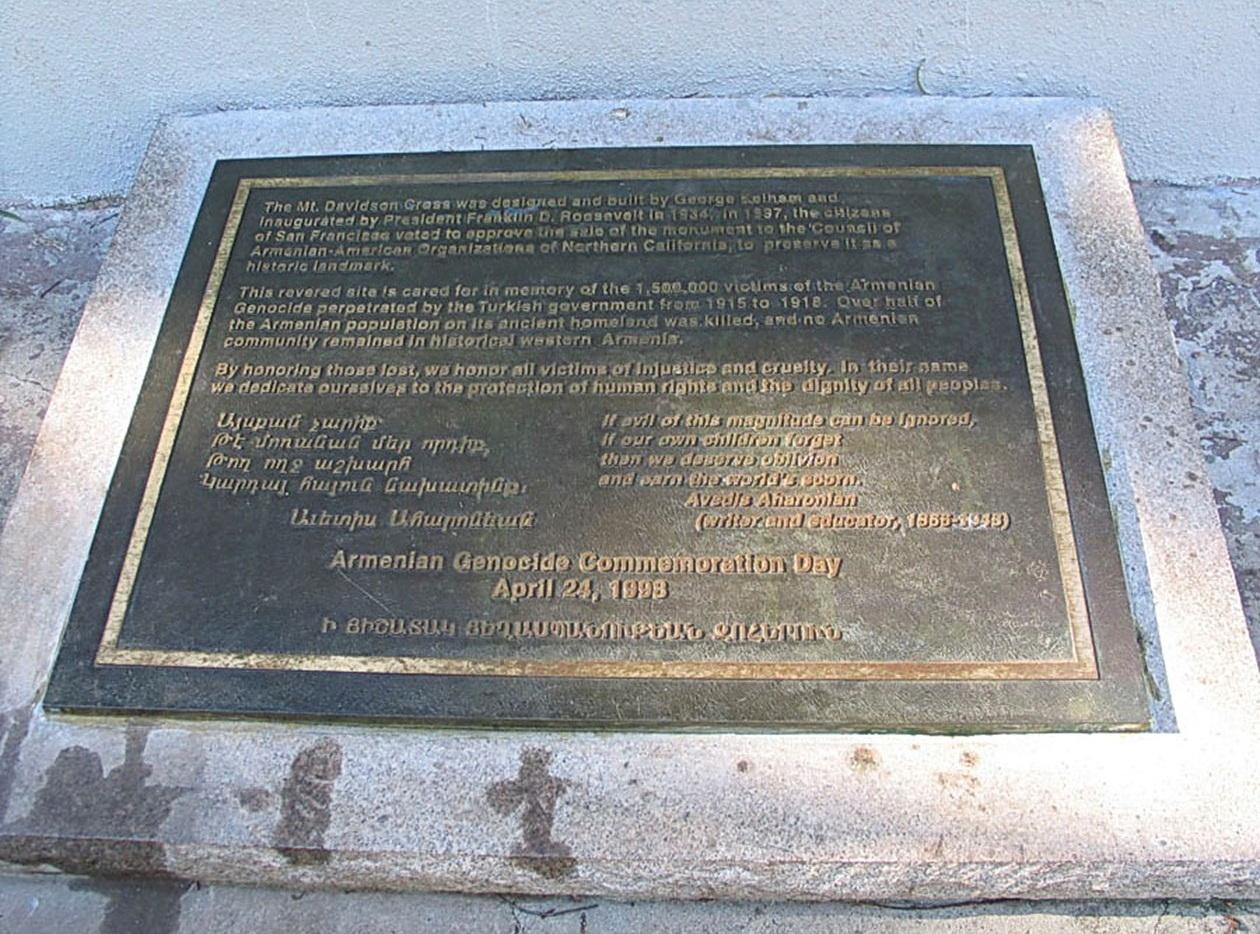

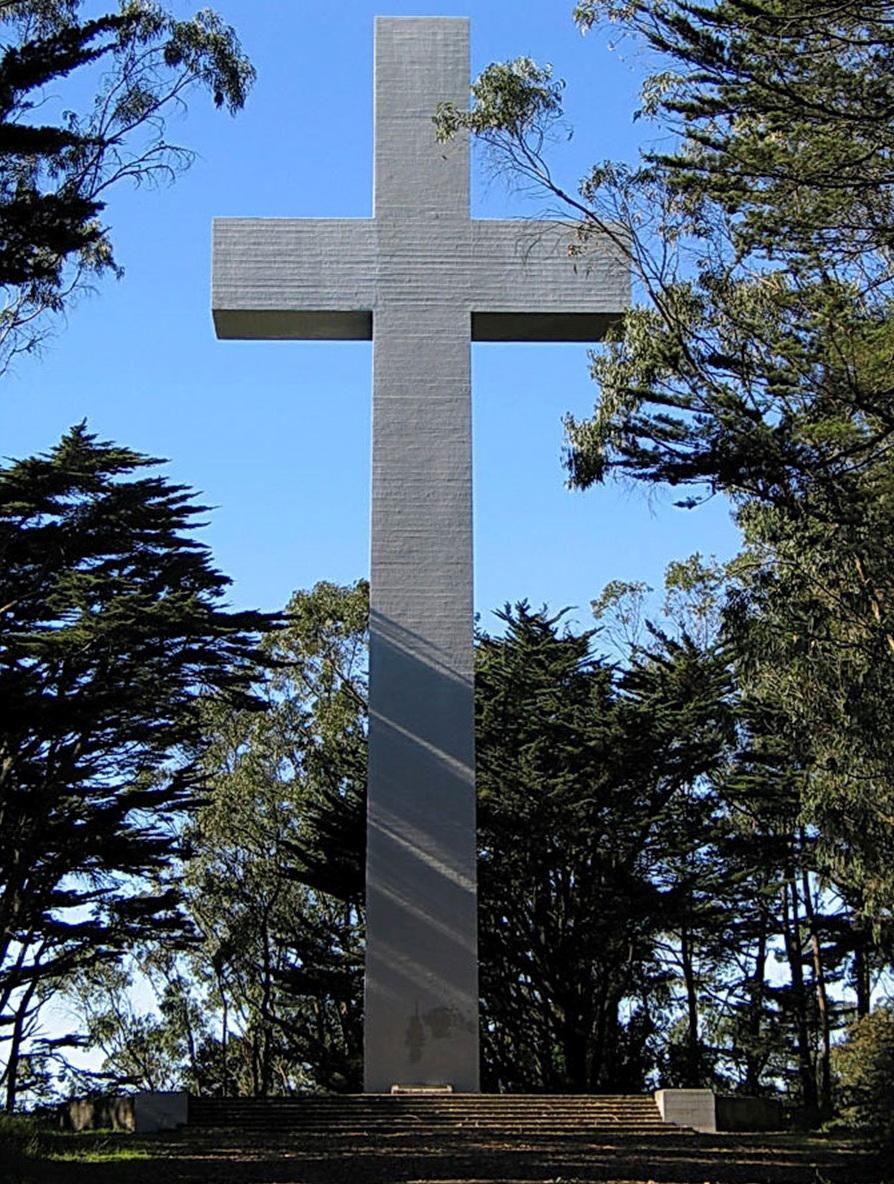

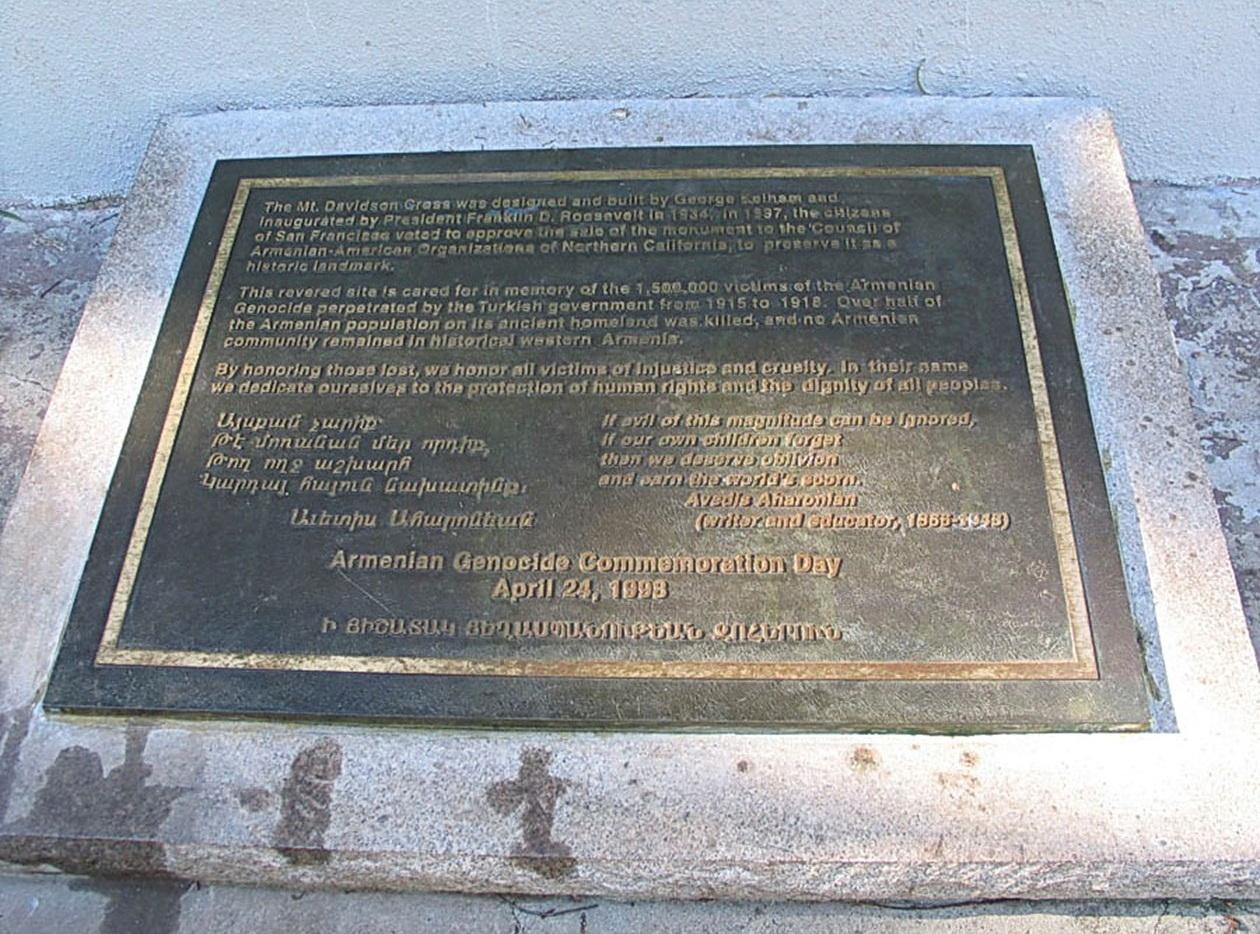

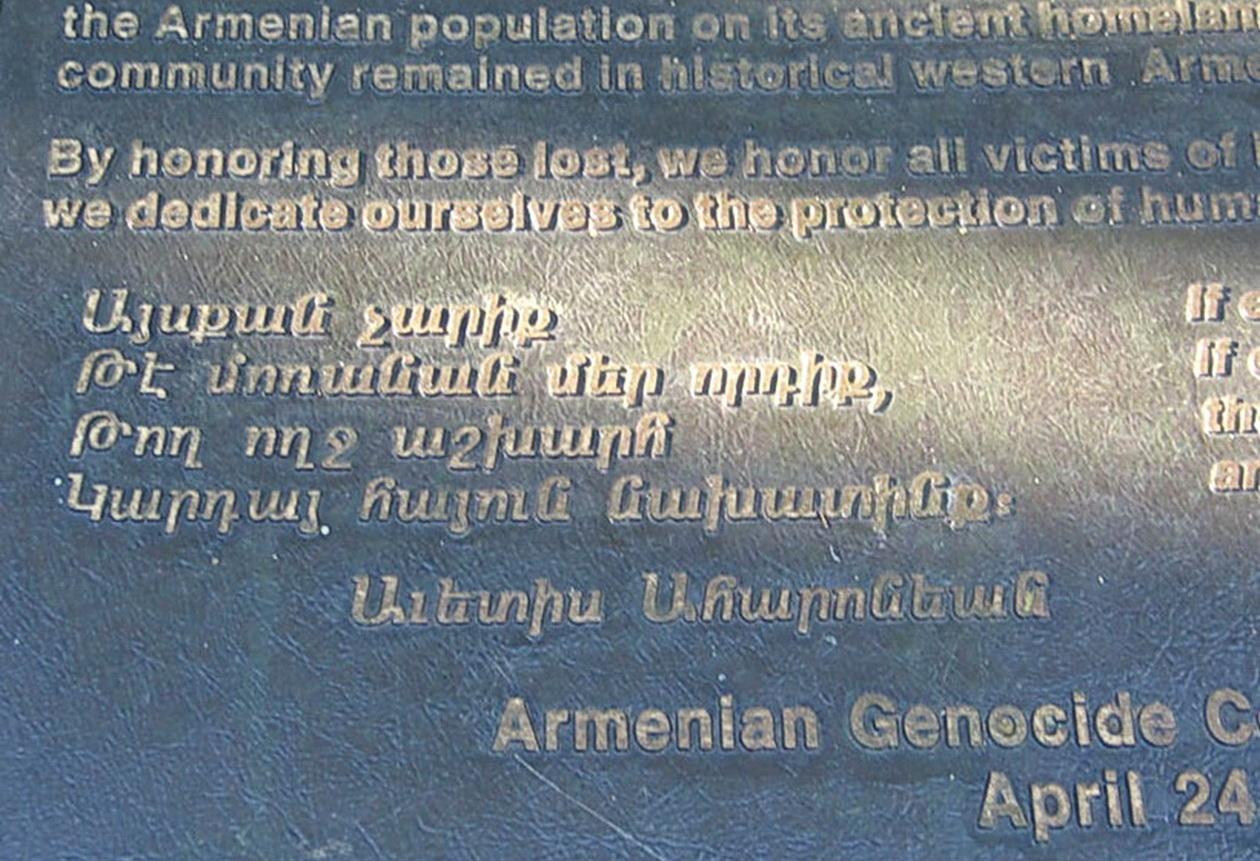

The Mount Davidson Cross

One particularly moving memorial to the Armenian Genocide in the USA is the

impressive Mount Davidson Cross

overlooking San Francisco and the Bay area.

It is 103 ft./31.4 m. high, comprising many tons of steel and poured

concrete, and has a history dating from the 1920s and early 1930s. The huge cross is indeed an imposing memorial

to the Armenian Genocide. After much litigation instigated by the ‘Turkish side’ against its being used as

a remembrance to the victims of the Armenian

Genocide, arguments were overcome, and it was finally dedicated in

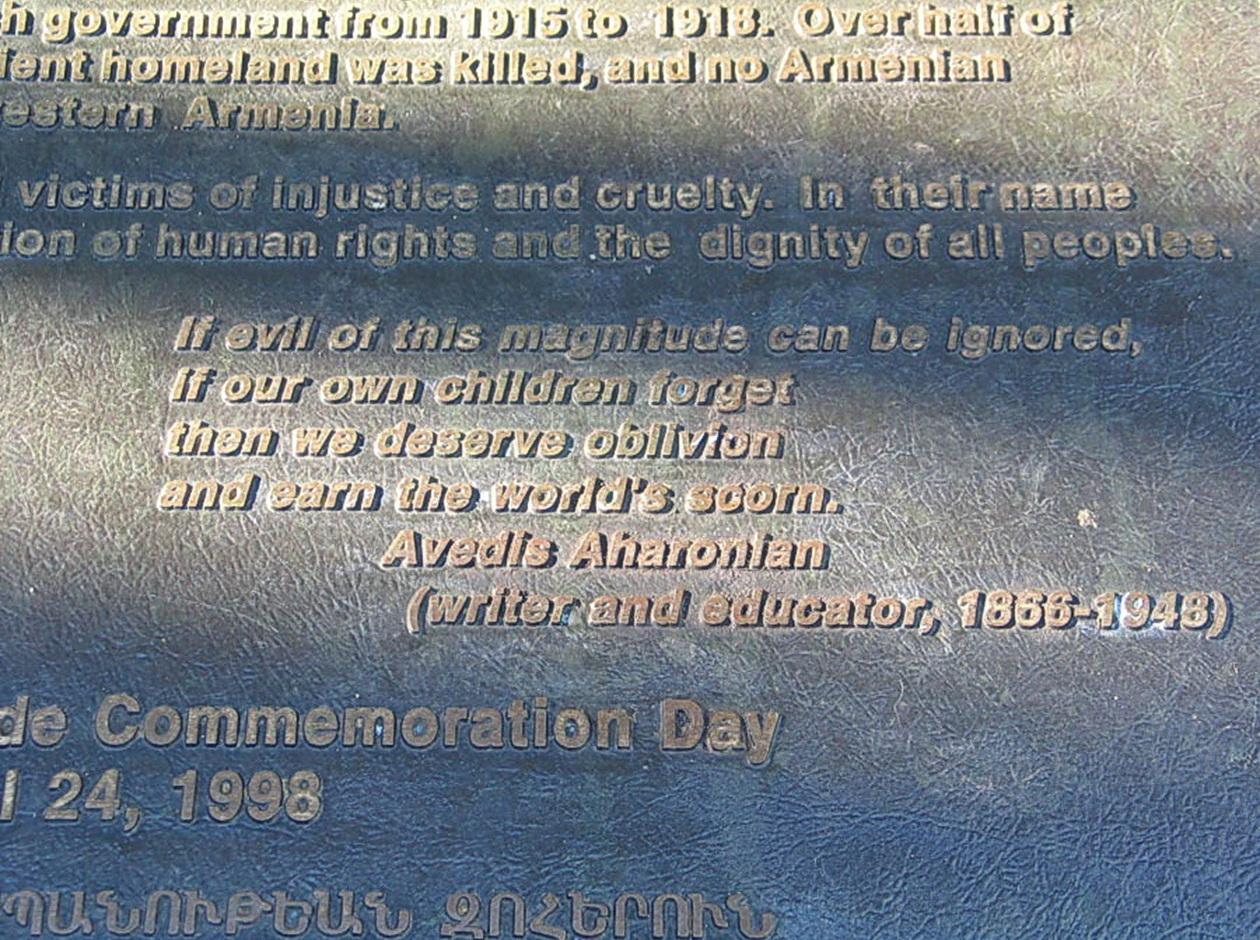

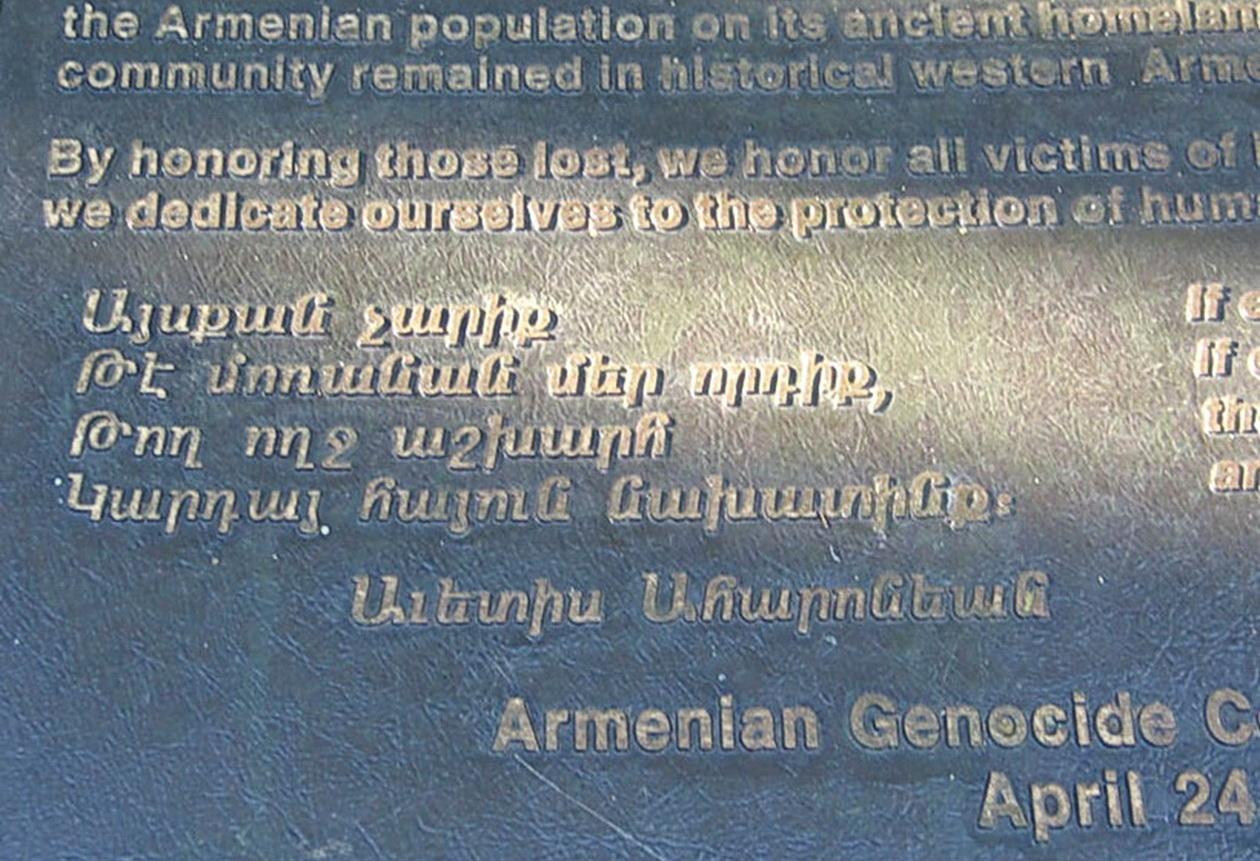

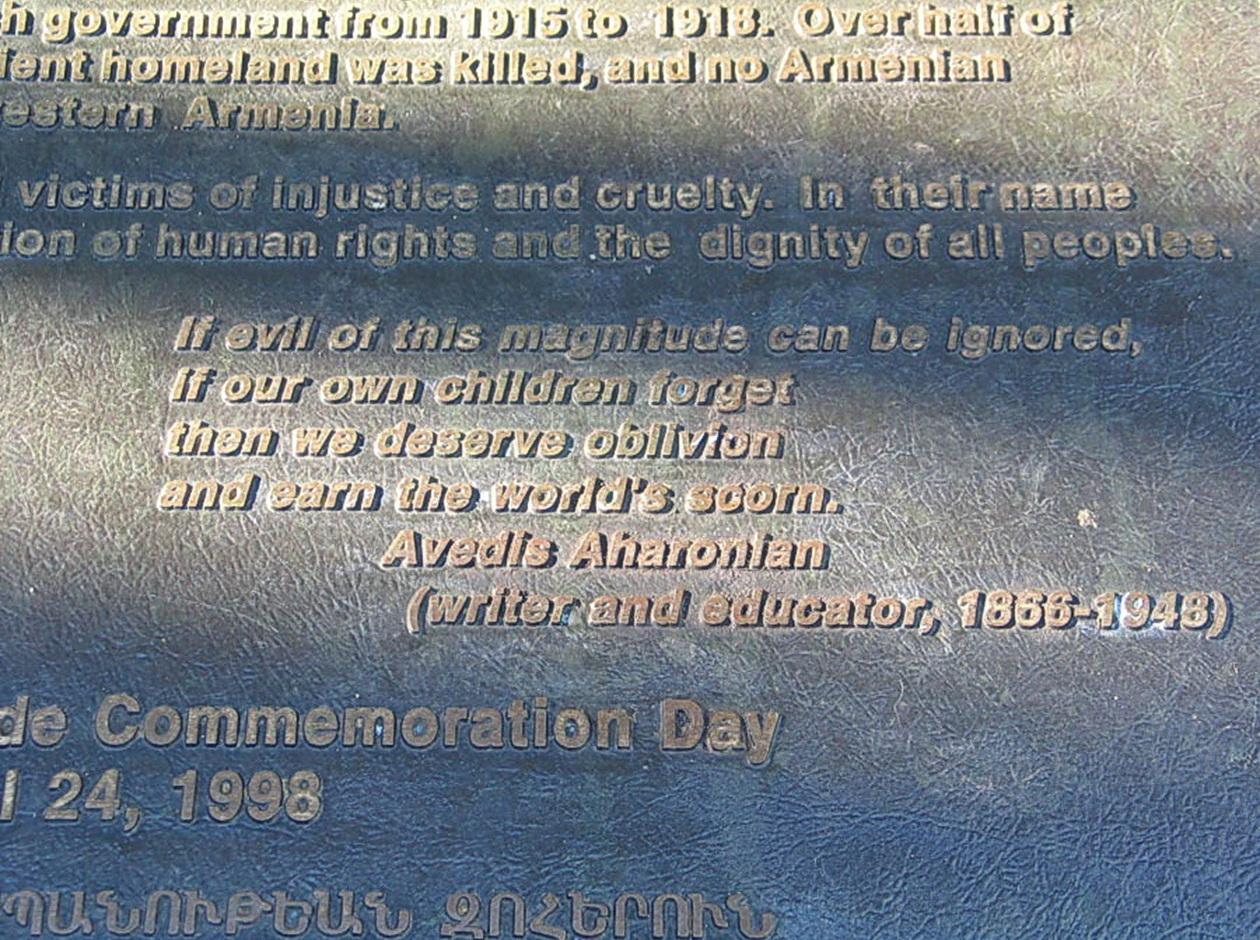

1997. The exhortation on the bronze

plaque at the base of the cross, quoted from Avedis Aharonian (1866-1948), Armenian writer, critic, poet and politician on remembrance of what the Armenians in

Ottoman Turkey underwent, is very appropriate and revealing (see Figs. 31, 32,

33, 34 and 35). It reads in English

translation:

“If evil of this

magnitude can be ignored, if our own children forget, then we deserve oblivion

and earn the world’s scorn.” (The poetess Diana

Der Hovanessian was responsible for the translation

from the Armenian original which is shown in Fig. 34. (personal

communication.)[46]

Fig. 31.

Fig. 32.

Fig. 33.

Fig. 34.

Fig. 35.

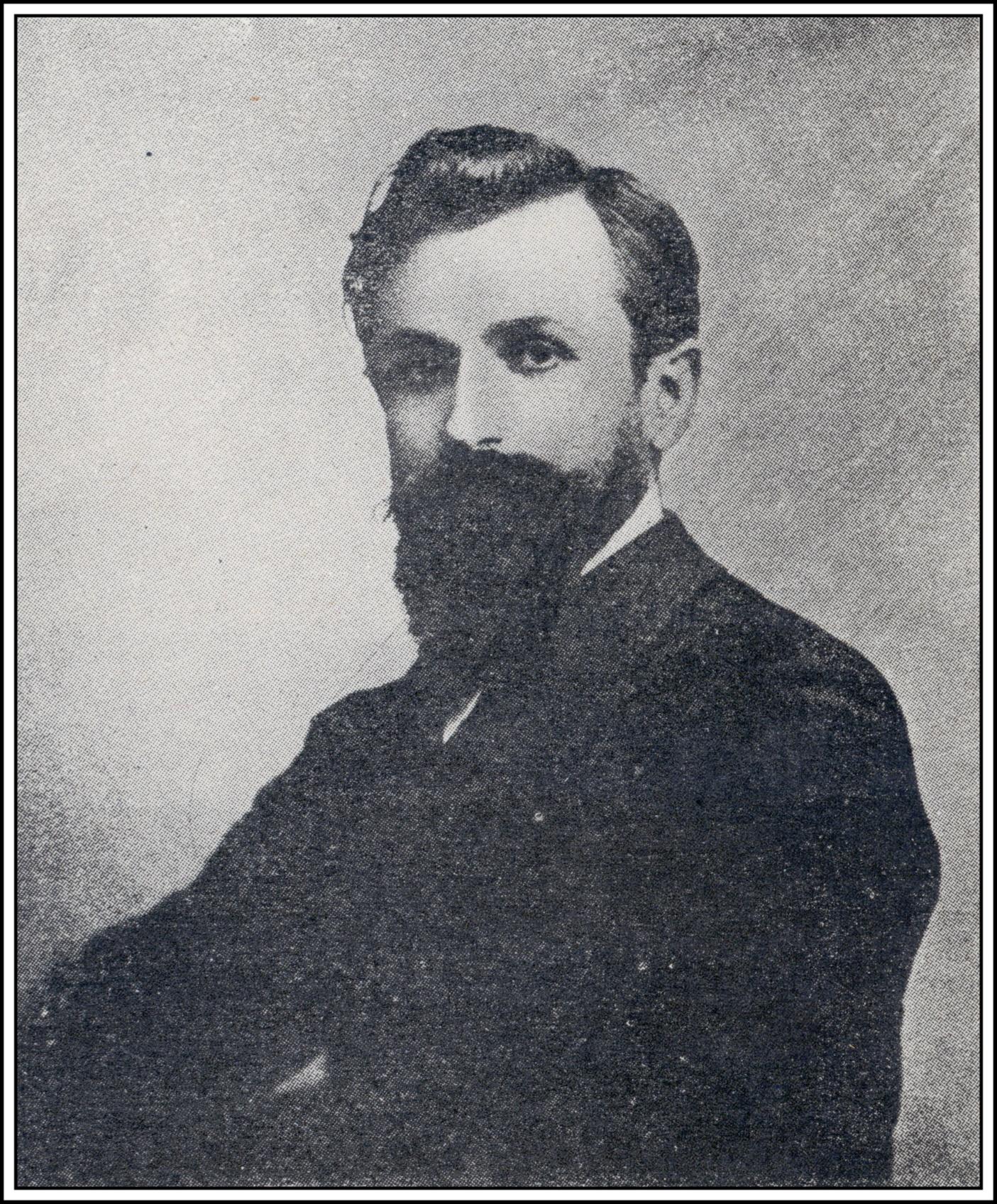

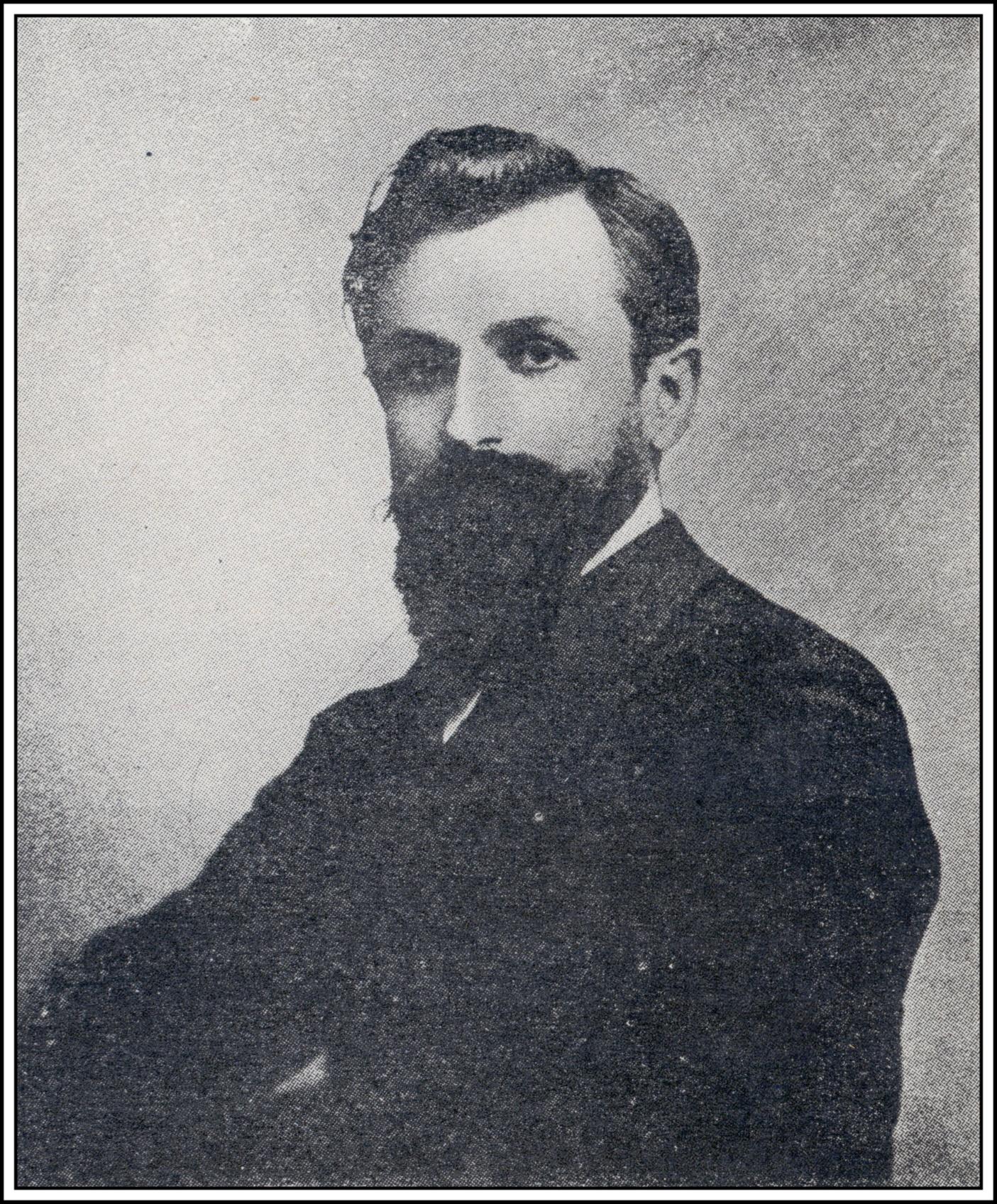

Avedis Aharonian

(1866-1948.)

Some

have suggested that there has been much too little closure of the very old but

still festering wounds dating back to the period of the Genocide and even considerably earlier. Proper mourning to lay the matter of murdered

ancestors and tormented grandparents, parents and

relatives to rest once and for all, has clearly not yet taken place. This is well reflected in Armenian

literature.[47] Like many others we believe it is impossible

to forgive if there is no admission of the reality of a genocide committed,

much less acceptance of some responsibility.

It is well to recall the quotation on forgiveness from Alice Walker, and

what has been voiced in an important encyclical from Pope John Paul II.[48] Walker wrote “All we can do is attempt to understand their causes and do everything

in our power to prevent them from happening, to anyone, ever again.” (Alice

Walker Overcoming Speechlessness

(2010).

More

abstract responses to the question of ‘What

do the Armenians want from the Turks’? could be offered by others. These might well be difficult to understand

by those who have no personal connections.

In that case, “Justice” is the

word that frequently enters into the reasoning.

Most

would agree that the word “justice”

is a politically pregnant word as well.

Justice for whom? Justice for

what? There is a phrase chiseled in

stone on the façade of the old Worcester County Massachusetts Court House

building “Life under Just Law is

Liberty.” A very lofty and noble

sentiment indeed. It would be enhanced

considerably if “and Uniformly Enforced”

were placed before “Law.” [49]

Then

there are a number of more pragmatic aspects of the matter of genocide

recognition that many on the Armenian side still insist must be resolved. This includes a full apology from Turkey. Not an apology of course for today’s

Government of Turkey having initiated and committed the genocide. All those involved

in planning and executing the genocides in Ottoman times have long since been

dead. The apology from the so-called

Republic of Turkey is demanded because successive Turkish governments, bar

none, from the early republic to the present day, have denied the reality

of the Genocide; hence in their eyes

there is no need to apologize. [50]

Few,

other than the descendants of Armenians and massacred Christian groups, have

even surmised, much less noticed, that the Republic of Turkey was built on the

bones, ashes, property and wealth, of the murdered