Armenian News Network / Groong

_______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

MEMOIR OF

GENOCIDE - 1915 to 1920

THE STORY OF AN ARMENIAN BOY

BY

NAHABED CHAKRIAN - (1904 - 1993)

Armenian News Network / Groong

January 5, 2022

by Abraham D. Krikorian

and Eugene L. Taylor

Probing

the Photographic Record

LONG ISLAND, NY

_______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

CONTENTS

About Nahabed Chakrian

Foreword

Acknowledgment

Notes

Memoir of Genocide: The Story of an Armenian Boy

Translated by Abraham Der Krikorian, Ph.D. (with maps added)

Appendices:

Documents

Suggested Readings

Book:- Armenian Sebastia/Sivas and Lesser

Armenia, ed. By Richard G. Hovannisian, UCLA Armenian History and Culture

Series, Historic Armenian cities and provinces, No. 5.

About

Nahabed Chakrian

By

Florence Chakerian

Nahabed Chakrian was born November 15, 1906. His baptismal given

name is from an ancient Armenian-Parthian loan word naha-pet,

signifying chief of the people, patriarch or

prince. He survived the exile and

massacre, was rescued, and at age fourteen began a new life in America.

In

time Nahabed matured, bridged two cultures, learned trades and established a family. He was a formal man. In his

relationships with family and friends he reflected his Armenian culture and

heritage. He was active and trim and, by

temperament, a romantic.

In

his memoir Nahabed Chakrian

introduces his home, nearby villages and members of his extended family but

adds little else about daily life. What

follows, at length, are episodes from his memory of exile. Anecdotes of survival alternate with descriptions

of trauma and death in the desert. Near

the end he summarizes life and family in the United States.

After

immigration to Providence, Rhode Island and an initial

adjustment, he moved with his father, stepmother, and stepsister to Bridgeport,

Conn. Nahabed

did not have the opportunity for formal education, as was the case for many

survivors. His son, Hagop, described his employment

as a dishwasher at Bridgeport’s leading hotel which eventually led,

fortuitously, to an apprenticeship with the hotel pastry chef. When this training established him, he

married Vartouhi Manoogian, seventeen, in 1925. He was then nineteen years of age. But a problem arose. Hagop

explained that the policy of the hotel required all pastries to be baked fresh

each day and the unsold discarded. When a hotel superior objected to Nahabed’s distribution of the day-old pastries to the

staff, he resigned.

Employment

elsewhere included a textile factory, the Rogers Silver Company and, during the

Depression, the Works Progress Administration for the Merritt Parkway Project

in Connecticut.

He

was active in the Armenian Church of Bridgeport then being established. Hagop remembers his father in its drama group, “The roles

were very dramatic.” Nahabed’s one lost opportunity, perhaps to fame and

fortune, was an invitation from Peter Paul Halajian

and Calvin Kazanjian, candy makers, to contribute $300 towards the launching of

Almond Joy and Mounds. He just didn’t

have the required sum.

Nahabed,

self-educated and an ardent reader, ‘… was always writing-- pages and pages,

including poetry,’ his daughters, Jean and Madeline, recall. Hagop adds, “Always

talking about politics and world problems.

He was stubborn, too, and unable to admit he could be wrong.”

His

hobbies included reading, acting, singing, tavloo

(backgammon), and cards. He chose to

believe that the adventures of Sherlock Holmes and Dr.Watson

were not fiction.

In

1929, with the onset of the Depression, when finding employment became a

problem, Nahabed moved his family to New York City.

Introduced by a life-long friend to a photoengraving firm, he completed

training as a cameraman, continued working in this trade for a half-century,

and retired only after a mild stroke.

Twenty

years after the deaths of his father, Caloust, and

his wife, Vartouhi, Nahabed

moved to California to be near his daughter and relatives. Two years later, in

February 1975, he married Mary (Maryam) Piligian,

a widow with grown children, whose parents were originally from his home

village in Sebastia. In his Memoir he described his

last years enriched with loving appreciation and affection for her and her

family, who were then added to his own.

All

who knew him agree that Nahabed lived with

impassioned intensity. He believed it

imperative to impress upon family, friends and the world, the exile, massacre and devastation of the Armenian nation and to

expose those responsible. With the

passage of years he committed his testimonial to

writing (now lost) and finally to cassette tapes beginning in 1988.

He

surely would have realized some small satisfaction in the rising tide of

discussion following the recent September 2005 controversial, first-ever

conference in Istanbul by intrepid Turkish scholars exploring the history of

the Genocide.

He

had heart surgery followed a few years later by a final heart attack when

living in the Ararat Nursing Home. He wife, Mary, had died. Nahabed

Chakrian’s death was on December 24, 1993 five years after the death of his sister, Gulizar, January 29, 1988. They are buried in Forest Lawn

Memorial Park, Hollywood Hills, in Los Angeles. Their families-- children, grandchildren and great-grandchildren—live today in New

York, California and Yerevan, Armenia.

Shake

Bedikian, in Los Angeles and David Joseph Hazarian, in New York are Gulizar

Chakrian Hazarian’s

surviving children.

Nahabed’s

sons and daughters are Jean Zvart Derbabian,

in Los Angeles, and Charles Hagop (“Jack”) Chakrian, Madeline Markarian, and Armand Chakrian, in New York.

Gulizar

and Nahabed hold a special place in our hearts and

minds.

Foreword

to the Translated Memoir

By

Abraham Der Krikorian, Ph.D.

An initial attempt at a translation

of this memoir from Armenian to English was made by a native of what is today

the independent Republic of Armenia, reared in the language of Eastern

Armenia. Baron (Mr., courtesy

title) Nahabed Chakrian,

however, uses for the most part Western Armenian, a language that today has

both a different style of grammar and vocabulary. In addition to Baron Nahabed’s

taped memoir in western Armenian, even that is made somewhat distinctive since

he learned Armenian as a boy, and then was successively exposed to provincial

Ottoman Turkish, then Arabic (as spoken by Bedouins at that) and again Turkish,

this time the Constantinople dialect, and later in America, English, of course!

The expansion of his vocabulary over

the years, coupled with his life’s experience with a more learned form of

Armenian (albeit self-taught), largely in his adult years, has resulted in a

distinctive mix of rather eloquent, in some cases flowery language, including

here and there, even a touch of Eastern Armenian! In a few places he elects to use English

words like “train” with an Armenian American accent, trehnn;

in other places he uses the more formal Armenian. In still another place he uses the English

word balloon; in another he uses the word story to indicate level in a

building. In short, the way Baron Nahabed talks is a blend of how and where he grew up, where

he was and what he experienced, and when and where he was as he read into a

tape recorder what seems to be an account of his memories, expressly written

for the memoir.

Because Baron Nahabed’s

language reflects in large measure the way Armenian immigrants to America

spoke, it seems appropriate here to insert in transliteration, albeit in crude,

phonetic form, some of the words or phrases used by him. In this way any reader who is familiar with

Armenian may be apprised of his rather free choice of language in any given

situation. Clearly, Baron Nahabed is not necessarily consistent in his choices; he

often uses different words for the exact same purpose in different parts of his

story. It will further be appreciated as

well that Armenian as spoken by villagers from Sebastia

in the Sivas region had its own peculiarities.

The first translation into English of

the tapes was, as it turned out upon vetting in mid 2005 by Dr. Krikorian of

Belle Terre, Long Island, shown to be very incomplete and very often quite

inaccurate, not just imprecise or incorrectly

nuanced. Moreover, all the tapes had

apparently not been gone through, certainly not very carefully if they had

been, and certainly had not all been translated. This was due, in part, not only to time

considerations, but also to the original translator’s lack of expertise in

English.

After a cursory assessment of the

initial attempt at translation was made by Dr. Krikorian, it was decided that

it would be best for him to undertake a fresh translation. The translation, such as was done by Dr.

Krikorian, a retired professor of Biochemistry and Cell Biology, at SUNY at

Stony Brook, was facilitated to the extent that his Mother

was a genocide survivor, a villager from Kerope, Körpe, in Kharpert province in eastern Turkey. His father was a volunteer, gamavor, who served in the French Armenian Legion in

Cilicia during the First World War.

Growing up in Worcester, Massachusetts amongst an Armenian immigrant

community, largely villagers, who spoke what might be referred to as ‘pre-1915’

and ‘immediately post-1915 Armenian’, along with more than a smattering of

Ottoman Turkish, he was exposed daily to conversational Armenian. And, as so many offspring of immigrants did,

he attended Saturday morning Armenian language classes. Later in life, he undertook the study of the

Armenian Genocide, indeed all things Armenian.

The Armenian he grew up with then turned out to be uniquely suited to

undertaking the translation. Indeed,

that form of Armenian is justifiably viewed by some as rather dated today. It verges on being unintelligible to those in

the present-day Republic of Armenia.

At

the same time as benefiting from the aforesaid advantages, the translation was

made difficult on several other accounts-- perhaps it is best to describe them

as technical reasons. First, the tapes

do not comprise, strictly speaking, a narration. Rather they are a reading of what was clearly

written down. Whether it was written in

its entirety or in the form of very detailed, rehearsed as it were, notes, is

not discernible. We guess it was written

in its entirety. (The text is not to be

had and might have been inadvertently discarded after his death.) It seems he did not destroy them since he

states that any reader, rather than listener, should excuse him for any

shortcomings. Baron Nahabed

reads at a fairly rapid pace most of the time.

In other sections, it appears that he, like so many of us, sometimes

cannot read his own handwriting, and struggles to keep the flow of reading. One can hear the pages turning.

For whatever reason, the level or

intensity of the reading, even with the volume turned up to the full extent on

a high quality audio tape player, was not uniform

among the tapes, or even within a given tape.

This meant that in order to translate, one had to go through it

virtually sentence, by sentence, first listening and getting the gist; then

re-winding and listening again and translating, and then again rewinding and

re-playing to make sure the translation was precise. Adding to this tedium was that the several

tapes made by Baron Nahabed (eight in all) were done

at different times, and were not well labeled, and as luck would have it, there

are long gaps and interruptions in the recordings. It has taken far more effort and time than

one might wish to admit to put them into what seems to

be a final sequence. (Incidentally, and very understandably, the final ordering

of the tapes by the first translator turned out to be incorrect, and this in

turn was reflected in the occasional incoherent flow of the initial

translation.) But it was not just the

lack of proper labeling; in some instances that has presented problems. Baron Nahabed

sometimes repeated a section, albeit on a different tape, perhaps thinking that

he had forgotten to record that part. In

such cases, he clearly went back to his text or extended notes to read them,

usually at a quicker pace than that of an earlier narration etc.

In the final analysis, these are all

minor quibbles, but it gives a feeling for the kinds of problems that might be

encountered in such efforts. It is both

fortunate and remarkable that this old gentleman, who had seen and gone through

so much in his childhood and youth, had the ability to organize his thoughts

and recollections so well, and furthermore, the determination to read them into

a tape recorder in his advanced age.

What seems even more remarkable is that his recall was vivid. We leave it to specialists to comment on how

and why such vivid recall is the ‘norm’ rather than the exception among

survivors of the Armenian Genocide. (The

translator’s Mother, friends and survivor-relatives

uniformly related to him as a child that the memories of those horrible years

were burned into their memories, readily admitting that their long-term memory

was often better than their short-term memories in later life. Indeed, the translator recalls vividly

hearing their stories related in remarkable detail, equal to Baron Nahabed’s in the least.

His Godmother, now 98 years old, similarly has vivid memories even

though she was a bit younger than Baron Nahabed.)

To continue

this commentary and attempt at analysis, Baron Nahabed’s

tapes are significant, not only for their content, but because of the

interesting narrative style. Baron Nahabed quickly ingratiates himself to the listener because

of his style and the sincerity he projects.

He provides what might be viewed as an apologia at the very outset,

pointing out that he is not endowed with any particular sagacity or scholarly

skills etc. Parenthetically, we think he

is clearly being too modest. Baron Nahabed is generally steady in his reading, breaking into

distinct and heart wrenching sobs in only a very few instances. And, he is generally

quite restrained. He is very glad to

offer thanks and recognition to those who showed him and others he was with,

any degree of kindness. And, in some

instances, he even sounds a bit like an Armenian priest, Der Hayr, or Protestant

minister, Badveli,

in the bestowing of praise and hagiological incantations upon those dear to him

who had departed this world. Only near

the end of his reading does Baron Nahabed seem to

express his anger, even fury, at the denial of the Genocide committed against

the Armenians by the Ottoman Turks, by successive governments of Turkey. He also gives a tongue thrashing to the

Germans for their complicity, and even goes so far as to call the French

[France] whores, pornig

Frantsatsi, for

having ‘sold out’ and abandoned the Armenians in Cilicia to the vengeance of

the Kemalist Nationalist Turks, even though she had ‘promised’ the right of

return and protection to Armenian survivor-refugees.

It goes

without saying that there should be no doubt as to the veracity of what Baron Nahabed relates.

Baron Nahabed is totally credible. In fact, one might call his style

understated. On a couple occasions he

titillates those listeners who may choose to read lurid details on what he saw

at Der Zor, and the other ‘killing fields’ of the

Syrian Desert. He gives details plenty

enough, but also passes over some places and says that he does not wish to

dwell on such and such a topic. One can

surmise that he knew that providing the additional gruesome details or bringing

up long-suppressed memories would have been enervating in the extreme for him.

More than a few times he asks

forgiveness on the part of the listener/reader for any of his

shortcomings. He deeply regrets not recalling

the names of several whom he held in high regard, and to whom he would be

grateful till the day he died for the help and kindness rendered him. (In one case, he apparently woke up in the

middle of the night and recalled names that he quickly wrote down, lest they

escape him once more.)

In a few cases, such as one in which

he relates the sexual exploitation of a young male friend of his by loosely

imprisoned troops from British India, Baron Nahabed

makes no bones of his boyhood naiveté, and failure to understand what was

happening to his friend who was “used like a woman.” He seemingly smiles at

himself for being so innocent. Indeed,

one can occasionally hear in a low tone, as if in the background, exclamations or chuckles.

He certainly seems to have had a good sense of humor. Moreover, one can readily identify with him

as he periodically shuffles his notes, and script, sometimes annoyed and

exasperated, trying to find where he is or where he left off, saying, "Pssssshhhhh!' and even pausing in one place and exclaiming

in English '"What the hell is this?"

Even

as Baron Nahabed has asked, more than once in his

tapes that he be excused for any shortcomings in his narration, the translator

and editor, Abraham Der Krikorian, Ph.D., and editor Florence Chakerian, both ask that he forgive us for any shortcomings

in these attempts to render his incredible, but all-too-typical story of

Armenian Genocide survivors, into English.

His Badmiutun,

his story, deserves to be told in its entirety and with as much faithfulness to

the original narration as possible. We

hope that Baron Nahabed would approve of this

concerted attempt to do the events justice

Acknowledgment

By Florence Chakerian

To

the above by Dr. Kikorian, I add an immeasurable debt

of gratitude for his many hours of thoughtful, literal translation. As

explained above, he rescued the manuscript and my commitment to Nahabed’s family.

Dr. Krikorian can be reached at Post Office Box 404

Port Jefferson, New York 11777-0404

Notes:

Nahabed

was my husband’s paternal first cousin. When I learned he had left his story of

exile, on tape, in care of his family, I offered to transcribe and preserve

them.

An

agreement for the translation was arranged in Albuquerque with a person whose

first language is Armenian, to be assisted in English by her husband, an

American. Charles Hagop Chakrian,

Nahabed’s son, paid a professional fee. We realized

only later that the translation was very superficial, totally incomplete and quite unsatisfactory. By chance--and surely

Providence--Dr. Krikorian learned of my problem and generously offered to help.

Dr.

Richard Hovannisian, Professor of History and Armenian Studies at the

University of California, Los Angeles, in reply to our letter wrote, in part,

on 7/21/2003: “We do not have an interview with Mr. Chakrian…the

tapes should definitely be copied for preservation…probably someone would have

to go over it to put into more readable and fluent English. We would be thankful to receive a copy…”

The

family recalls, however, that a student from UCLA did interview Nahabed “two or three times” at the Ararat Retirement and

Nursing Home, in California, sometime between 1900 and 1993. It may be that the student didn’t turn in the

assignment. I venture to guess the

student may have been intimidated by the sheer volume and intensity Baron Nahabed offered as a subject!

I

trust that the editing into established English syntax, though not always

consistent, is acceptable and remains faithful to Baron Nahabed’s

distinctive narration.

The

original tapes, with added audio DVD disks duplicated by Dr. Krikorian, and the

manuscript of the Memoir are for the family. Additional copies of the Memoir

are available for related family members.

The

tapes are duplicated, as recorded, and unedited for the time lapses, interruptions and other problems that Dr. Krikorian

discusses in detail. His annotations throughout the text provide a glossary and

illuminate Baron Nahabed’s use of language, custom, place-names, and events.

The

translator and editor added the subheadings. Some information, though sought,

is still missing. The variant spelling of names and places reflect historical

and geographical changes since 1920.

Florence Chakerian

Albuquerque, New Mexico

December 14, 2005

MEMOIR OF

GENOCIDE—1915 TO 1920

THE STORY OF AN ARMENIAN BOY

BY

NAHABED CHAKRIAN

Tape I, side 1

Introduction

“This

story is not a treatise, guk’t mi cheh.[1]

(See Endnote1 at end of the Memoir Proper). I have neither special power, garoghutiun, nor do I have any special intellectual

capacity, imatsanagutian, grace, shnorh, or imagination, yerevagayoutian. Nevertheless, I attempt to undertake this

story with these limitations. Before the deportations, deghapoghoutiuneruh,

I received some schooling for a year and a half from Melikzadek

Balumian of Zara village, Orghormiadz

Hohkin.[2]

Because I so wanted to study, I never forgot whatever I had learned from my

lessons at that time. During my wanderings in the deserts of Arabia, I would,

from time to time, find pages from the Holy Bible and Gospels that had been

scattered about by the winds. I would keep them, and by burying them in the

sand, I could retrieve and read them. In

that way, for a period of over four years, I read these pages over and over

again, and never forgot my Armenian tongue, neither my reading nor

writing. After the war, when I found my

father and we went to Bolis, [Constantinople,

the capital of the Ottoman Empire,] I wanted to continue my schooling but my

luck was that I could not. Therefore,

whatever I have wanted to learn through life has been self-taught.

“For

these reasons, I wish to beg the pardon of all those who might read my notes in

the future, and find errors—which I am certain they

will find.[3]

These writings and these memories have been written and recorded very

many years after the events. But despite my age and possibly failing, memory,

what I have recorded is the truth and not a single word has been superfluously

added. If I could only remember every

detail of those four years in the past, of what I saw, what I heard, what I

experienced, I would certainly be able to fill several volumes. I am sure educated persons have already

written volumes about similar experiences.

I myself have not read a single one of them.

“One

group of exiles, gaghtorner,

[euphemistically referred to by some as émigrés],

went towards Baghdad, others were driven, kisheltsihn, towards Damascus and

others in still different directions.

The exiled groups, gaghtorneru, who went these two routes [Baghdad and Damascus] were not slaughtered, godoras —they were tortured, charcahrvetsahn, and experienced different, zanazan, torments, danchank, but they were not slaughtered, godorasi chi eghahn. Having said this, I once again beg your indulgence and request your forgiveness for any mistakes. I, Nahabed Chakrian, offer this account, with respect, to honor all my descendants and those who might wish to learn.

“July

24, 1988. Today, it is 74 years

[actually 73 years] after the events of the exile, aksor, of all those Armenians

born in Turkey, Dadjigastan,

[land of the Turks, or Dadjigs,] towards

Arabia, during the First World War and during which many lost their lives. I am trying to relay to the best of my

ability all that happened. My sister, Gulizar, and I underwent the deportations and became exiles

and survived that Great Tragedy, Medz Yeghernin, [eghern

normally means crime and collective murder; but is used to designate that

calamitous event of premeditated genocide].

Home

“I

will return now to my biographical background.

I was born in one of Sebastia’s villages in a

place called Araksa, or Alakilise

almost, qrete,

fifty-five miles, mughon,

from the capital.[4]

All the nearby villages were

Armenian. Kayrat village [pronounced Kye-raht, emphasis on first syllable] consisted of about fifty

or sixty Armenian families. Tekelu [pronounced Tekeh-loo,

emphasis on both syllables] forty houses.

Zara village, built in former times by the Armenian Queen Sara as

a summer residence, became a village of both Armenians and Turks. The village of Kharaboghaz,

four miles away, was Armenian. [Note: Kharabogaz,

despite it being a purely Armenian village had a Turkish name, meaning ‘Black

Throat’]. I personally am not familiar

with Kharaboghaz but according to my

grandmother it was not a very big village.

She lived there when she went there as a young bride with her first

husband.[5]

“Now,

ayzhm,

let’s turn our attention to our village and locale. It consisted of approximately 450 houses or

families and derived its name from the church, Alaksa,

in Turkish, Alakiliseh. My family surname, maganoun, is Chakrian. I have not encountered this name, before or

after—except in our family.[6] My grandfather’s given name was Hovsep; my

grandmother’s, Diruhi; my father’s, Caloust [var. Kaloust] and my

mother’s, Varteni.

I had three sisters, Gulizar [equivalent of

Full of Flowers or Flora], Giultana [equivalent of

Rosina or Rosamond], and Tshkouhi [Queen or Queena,

equivalent of Regina], and four brothers, each of whom lived no longer than a

week or month. [Note: A brief statement or proverb in Turkish follows at this

point but am unable to translate. It seems

to start with the Armenian word now, ayz’m and the Armenian phrase ‘let me turn’ to, dahrnahm,

followed by Turkish…]

The Turkish Soldiers Arrive

“In 1914 my father was to be found in Bolis, the capital Constantinople. At the beginning of the month of January 1915

some 1500 Turkish soldiers, zinvohrner, were brought to our village. Half the people were ejected from their homes

to make room for them, and the other half were interspersed among the

families. In that manner the soldiers

were accommodated, haytatetehtsihn.

For two months the villagers were obliged to provide meals for the soldiers

every day. How many families struggled

to do so! After two months the village

became depleted. When the soldiers

finally left, the entire village was emptied of food.

“My father was a miller, charghatsban, but as I mentioned,

he was in Bolis at that time. The mill in our village stayed closed and

after providing the 1500 soldiers meals and bread for nearly two months, all

the villagers were completely exasperated and without provisions.[7] There were a couple of other villages that

had mills but only one was open in a Turkish village named Adamfaki,

[now called Adamfakizir] some four to five miles

away. The owner of the mill and village

leader, kiughi beduh, one

Ibrahim, was a friend of my father and for quite a few years my father had

dealt with him. So, my grandfather and

three unrelated women decided to go to that mill to grind flour since there was

no other choice. They went, but on their

way back, about two miles from the village, they were attacked by a couple of

deserter soldiers, paraghtsakan zinvorneru,

hiding in the mountains. The four of

them, including my grandfather, were brutally murdered, charachan spannuverayn, by the soldiers who then

stole their flour and their donkeys, avanagneruh.

“The bodies were found within hours by a shepherd, hoviv, and very

quickly the news reached the people in our village. Our village priest was

concerned that the bodies be brought to the village cemetery so that they

should be put to proper rest. I was

affected so much by the death of my grandfather that I became ill and confined

to bed, angoghin,[8] the next day.

Exile

A week later, six policemen, ostiganer, came

from Zara to our village announcing they were taking us there. We would be allowed to take food with us for

only three days since we would be returning after the third day. Those who owned carts, saylo, [pronounced sigh-low] were

able to get on their way in carts. The

rest went on donkeys or on foot. Not

much was taken since we were to return soon.

“In the village no young males, yeridasart dughamart,

were left; they had already been conscripted into the army or killed. Only the elderly and infirm men and the very

young remained.

All the women of the village

closed the doors to their homes.

Believing the soldiers, we set out on the road. “I was in our cart lying in my grandmother’s

lap. Melkon,

my aunt’s husband, was driving our cart.

My aunt, my mother and three sisters followed behind. As we started on the road, at the doorway of

our house, our faithful, havadari,

dog, Akbash’s

head appeared.[9] I lifted my head from my grandmother’s lap

and called the dog. He ran towards us,

leapt onto the cart and began to lick our faces and

hands, and those of my grandmother. He

then leapt off the cart and ran away without looking back; he heeded neither my

voice nor that of my grandmother. He

reached the house and remained there on the doorstep. That dog, which had gone with my father to Erzeroum, Sebastia and villages

and cities, seemed to understand human conversation. He went out early in the morning with my

father and awaited his return. Now, the

house where he was raised and where we fed him was where he stayed and, from

fidelity, would not separate from it.

“The people of our village had

been on the road for about an hour and a half when we reached a valley, tsorimi, Burnayeen [?]; we settled down there. I don’t know why but the people of Kayrat village and the people of Tekelu

joined us. The next day was Easter. They brought about 350 goats and sheep from

our village for distribution among the people.

Easter day we started on the road under the escort of eight soldiers and

police [zinvor

and ostigan

are the words used]. We continued

traveling watched by eight Turkish soldiers.

Their leader was the killer, uchvagordz,

Mayilbek, of Zara.

“In four or five days we reached

the city of Divrig. There they took away the carts from those who

had them, and instead of payment in exchange, they gave us one donkey for the

expropriated cart. The elders who were

not able to continue walking-- my grandmother was one-- had to be left by the

roadside under the shade of tree, and in this way we separated. For the first time in my life

I experienced this kind of pain and sorrow.

“We exiles did not enter the city

of Divrig.

We passed by it. I don’t remember

how long it took us to reach Arabkir but we didn’t enter the city. Exiles remained in the garden areas, aikinneroo,

outside the town. We had never seen such

a filthy place. The next day they put us

on the road again. I don’t remember how

many days it took us to reach Malatia.

There, too, we didn’t enter the city.

After spending one night there, we finally reached Kharpert [more

precisely Mezireh, the lower twin town some

three miles beneath the upper city of Kharpert], settling in a garden

area. That same night two armed men came

on horses from the city and violated, purnapareetsihn,

a young girl, aghchig, from our

village. The old men and youngsters were

so frightened they did not interfere or voice an objection. They were unable to dare doing anything.

“In the morning, we set out again

on the road and in two days reached a narrow mountainous place closed in by

mountains on the left and right, a valley amidst rocky slopes. The caravan, garavanuh, settled there. On the right side of the valley was a red

mill; ten to fifteen steps in front of the mill was a

spring, aghpiur. Behind the mill, was a mountain, lehrmuh, covered

with trees, hibd dzarevno. There we spent the night without any adverse

happenings.

“The

next day, near afternoon, my sister Gulizar and I

went to the stream for water to make tahn from madzoon bought the day before from a

Kurdish woman. [Madzoon,

Armenian, diluted with water, makes the refreshing drink tahn.] As we approached, armed Kurds on guard at

the spring appeared from behind the trees.

Terrified, we rushed back without any water. Already the gendarmes, [pronounced genderhr-mehnneruh]

had begun to separate the men and older boys, and were

moving them towards the mill. Till then

the gendarmes had been sitting and had not been close by.

“We

tried to hide my Uncle Melkon under two small

blankets, vermugs, while my sister Tshkouhi

and I sat on him. Three to four minutes

passed. But when my Uncle couldn’t

breathe, he pushed us aside and thrust himself out from beneath the blankets.

“With

a sad, dukhur,

countenance, kissing my aunt and the rest of us, he reached into his pocket and

took out his purse, kusag,

pouring all the money, tirahmuh,

into the lap of my sister Gulizar. Sadly, he gave us his final departing words

that to this day ring in my ears. ‘My

dear ones, more or less I cannot say…to go, there is, but there is no return--’ Here his words

remained incomplete, ges-hahd. Two gendarmes had reached us. One of them saying roughly, ‘Stop

complaining! Son of a pig! Mi dirdiral, Khinzer oglu khinzer.’ They pushed him towards the mill. Cries or

shouting in those mountain gullies went unheard. Ten to fifteen minutes later, the gendarmes

had already finished their detestable, garshili, deeds.

“The

leader of the gendarmes ordered the people be moved on their way with whips, kharazaner. We

were again forced to embark upon the road.

It was the last we saw of our older boys and men.

“When

we lost my Uncle Melkon, my sister Gulizar became the head of the family. My aunt was a delicate woman; my mother weak;

and my second sister, Giuldana, inexperienced, anvarzh. My little sister Tshkouhi

and I were helpless. If my older sister

had not been burdened, pergnavornadz,

with a nine-month old baby girl, the situation might

have been easier.

“As

the days and weeks went on, the situation became more difficult to bear. The cursed gendarmes delighted in making

people take indirect mountainous routes, rather than more leisurely direct

paths, and chased and drove the exiles to deliberately cut their number. I felt

that I, too, would have this fate, vijaguss, of dying in childhood. They had but one purpose, nbadag. Day by day, the children and the elderly were

becoming weaker. Those with physical

disabilities could endure little more.

We became concerned, mainly, with looking after ourselves. Ninety-five out of a hundred had reached this

state.

“Eventually,

after several days, we reached a mountainous place. On our left it was reminiscent

of Sebastia, and on our right, a lake, lijovmi. [Lake, most assuredly Lake Goeljuk] We

exiles settled down. It was not yet

mid-day. The wind was a little strong

and the lake a bit stormy, alegosial.

“What

we saw, first, was hundreds of massacred bodies, face down in the water, their

intestines fallen out like inflated balloons.[10] I had never seen such a sight in my

life. The horror is still deep in my

heart. It is frozen permanently; I can’t

forget it.

“Tens

of people from our caravan, unable to tolerate more agony, threw themselves

into the water. It was there, you see,

where my sister Gulizar, following the example of

other women, raised her first-born baby daughter and threw her into the lake.[11] My sister, Guildana,

horrified, plunged in to get the child out.

But Gulizar grabbed [khulelov] the baby from her arms and again threw her-- further out, deeper,

aveli khoruhnk--

into the lake. Human feelings and

parental love was weakening, dugaranah, and losing under the

strain and stress.

An

Example

“After

that event, some five groups from different villages and cities joined us. Our number, mer kanaguh, increased substantially. One was a column, garkmi, from Chimisgedzek;

another of Sebastatsi women; a group from Zeytoun and others from elsewhere. Following several days on the road and one

and a half days from Urfa, we settled somewhere in the mountains. The sun was nearly set.

“Suddenly,

the quiet was broken. About a hundred

feet from us, a man from Tekelu, who had

survived thus far by dressing as a woman, was running. They grabbed him and tied his hands behind

his back. They stripped him and

suspended him head down from a tree.

They wanted to make an example of him, saying ‘Let it be known, and see

what would happen to any coward who would attempt to deceive the Ottoman

government.’ A sword was drawn, and the

naked body, top to bottom, split in two.

The onlookers, fingers in their mouths, were horrified. In that dreadful place we spent the night,

but I don’t think anyone who had seen such a horrible thing was able to close

his eyes and not recall what happened.

We had become somewhat accustomed to the numerous and various trials and

tribulations happening on the road of exile in our convoys, but we had never, yerpek, seen a

body cut asunder!

“The

following morning at sunrise we were ordered on the road again. We hadn’t been on the road for more than

fifteen or twenty minutes when I saw those moving on ahead were being driven to

the left. They turned their heads and

closed their eyes when passing by. When

our turn came, we saw on the left side of the road about eight or ten feet

ahead, the naked body of a young man with shaggy black hair and a bloody,

gaping bullet, kuntag, wound, some eight fingers in

width. This sight horrified and saddened

the deportees. It was as though a sign

signaled our own future and fate.

Urfa, Biblical Edessa

“We

reached Urfa the afternoon of the next day. Without going into the city,

the first guesthouse on the right side of the road became filled with

deportees. [Curiously, Baron Chakrian uses the word huiranots, rather

than the more widely used Turkish word khan]. We, too, were to be found in that group but

an hour later we were taken out and moved to the city into another

‘guesthouse’. For the first time in the

deportation, the people of villages and cities became separated-- mothers from

their children, family members from family members, villagers from the same

village, and city dwellers from the same city.

Out of a 100, some 98 of us never saw loved ones again.

“They

located us quite close to the market, shugah. By that time

we had changed, as though half-animal, gess anasoonih, and unashamed [of our appearance; there are

many photographs of the

pathetic condition of these exiles.]

“Urfa

was a clean, spacious and beautiful city.

In the center of the market there was a beautiful well-provided garden

with trees [Note: Not able to distinguish whether the Armenian word for trees, dzar, or flowers, dzaghig,

is used here] and a coffee house [Note: the Armenian suhrjahran rather

than the Turkish word khayvakhaneh

is used] where, in particular, the wealthy of the city would frequent. I had the luck to go there twice—not to pass

time or for amusement, but to beg. Not

once, though, did I find anyone who put his hand into his pocket, be he Armenian or Turk, to give me either five or ten paras. [Note: the copper Turkish coin, a

para, was a fortieth of a piaster,

about a ninth of a cent]. Every evening,

however, before sunset the local gardeners, who had not sold their fruit, would

distribute it to the beggars and the poor.

In that beautiful city we stayed two weeks.

“There

were two kinds of ovens, purrehr,

there to bake bread. One was for

unleavened bread and the other for yeast bread. [Note: the rather uncommon

Armenian word for ‘yeasted’, tutkhvahdzin is

used.] Those unleavened breads have to

be used without cooling or drying. Once dried, it hardens and becomes brittle,

rock-like.

“In

Urfa I met an Armenian passerby.

I don’t know what work he did.

Each evening before sunset, he shopped in the market and then took a

little orphan, vorp, to his home. His wife would be waiting and have a table

ready. They had no children of their own. They seated the child, boy or girl,

with them. In those two weeks I was fortunate enough to meet him twice and

invited to be seated at the same table and treated as if I were theirs. Even after 74 years since those days, I’ve

never forgotten the kindness and benevolence of their hearts. And I will never forget unto my own grave to

ask the Lord God to bless his soul and to pray that this fully worthy man has

been taken unto His Kingdom.

A Terrible Happening

“About two weeks later, about 4 o’clock, three or four

Turkish gendarmes came to the khan and ordered us on the road. Our past trials tribulations of deportation

were not yet behind us. We thought their

intent was for the stragglers to be swept up for better control.

But

those plotters, tavajanneru, had a different purpose. Their plan was to separate and render us

completely helpless. After having moved

the deportees on, half had been kept behind.

In that way, again, different things happened to different groups. People became separated from one another--

mothers from children, sisters from brothers-- once more. All the people ejected from the city, all the

people who had been distributed amongst all the khans of the city when assembled and taken together, were about

35,000.

“We

reached the desert. There in the open we

spent the night. Next day, again at

night after having traveled, we spent another sleepless night in the open. I had a bad feeling that something was about

to happen and it did. That unforgettable

tragedy I have never forgotten and shall not until my grave for it remains deep

in my heart like a fixed piece of metal.

I had planned to take this secret to my grave if I had not decided to

commit this crime, yegherkuh,

to writing.

“

Around ten or ten thirty-two gendarmes came to where we were sleeping and took

my sister, Gulizar, crying and screaming, away. She was raped by six Turkish gendarmes.

The Railroad Train

“We

reached a small village in the desert called Maljanaghad

(?) and spent the night on the outskirts

about a mile away. For the first time we

could see the railroad, yergatoughi, and the train at a distance. I had

heard about trains but never had seen one.

We stayed a day and a half. My

mother was craving something sour, tuttou. That became a

reason for me to go towards the train hoping to find it for her. I hadn’t realized,

however, I would be able to see it up close. When near I was amazed! It seemed to have a soul, hoki. Pshrrpsr,

it was hissing and blowing. Had I time

and been able, I would have stayed the whole day, fascinated. But, I had gone

there to find something sour for my mother.

I found nothing but a bit of bitter lemon from the storekeeper. That train was going to Haleb,

Aleppo.

My Little Sister

“We

were on the road again. After a short

while we reached a place with a creek or brook, arvagmi muh.

This had a narrow bridge, negh garmujov. Only

two people could closely pass or only one with a donkey. It became very congested. The exiles from other cities and towns that

had not traveled through Kharpert, who thus were not worn out and

decrepit, were uncertain how to cross through this narrow passage. They went into the water uncertain of its

depth; it was, however, only up to their waists. [Note: Baron Chakrian

is a bit hesitant here and seems to be struggling with his script.]

“Everyone

was pushing. Neither my two sisters nor

my mother were near me. My aunt and my

younger sister remained on the donkey in the midst of all this confusion. We waited nearly two and a half hours in

order to cross that damned, anidzial, narrow bridge to get to

the other side! Tshkouhi,

who was sitting as usual on the back of the donkey behind my aunt, succeeded in

getting off the animal and stood waiting for a few moments with my hand in

hers. I don’t remember in what way or

for how long we remained in that pushing and shoving crowd.

“Suddenly

I felt that my sister was no longer near me.

I was surrounded [long, emotional break in the narration here] and, as

much as I looked around, [it was as if] she had evaporated! I couldn’t leave my aunt on that donkey to go

looking for my sister. And where would I

look? Finally, during that separation, I

was able to somehow struggle across.

Crying, I didn’t know what to do.

My mother and two sisters were not around. Then, I heard a cry, ‘Brother, Brother, Yeghpayr, Yeghpayr.’

Looking toward the sound, I saw Tshkouhi, sitting on

the bank of the stream, waiting, her shoes off and her feet in the water.

“I

have yet to understand, and probably never will, how the women and men in that

great confusion had the courage and stamina to cross that bridge.

“Meanwhile, we were yet in another area of

water. I’m not sure exactly what it was,

whether a river, ked, or an, arvak, small river or stream, but it was not

a lake, voch lij. Here and there the running water had settled,

widening into gullies, with standing water in the partitioned ditches. Other places the running water entered into

cracks and crevices. I could see that by moving the donkey

[next to a height] I might be able to help my sister. We neared a wall and I helped her up and from

there onto the donkey in back of my aunt.

But again, after another ten or fifteen steps, we came to a spot where

the donkey had to jump, tsadgel. When he jumped, my sister thrown off the rear

of the small animal, tumbled into the water.

The donkey, with my aunt aboard, [long pause] ran away—braying, running

rapidly, arak, arak, and joined the

multitude.

“I

looked around on all four sides, chorss gormuhss, no one remained near us. My sister was seated in the water,

crying. As I helped her to the bank, a

gendarme appeared. He gave my back a couple

of sharp blows with a whip, saying, ‘Khinzer oglu, khinzer! Ulu nerederi olsun, son of a

pig…’ mounted his horse and left.

Scarcely two minutes later he returned with some young Arabs. They were apparently twin brothers, yergvorgiag yeghpaynehrayn. Striking me again with the whip, he grabbed

my sister and handed her to those Arabs.

One, holding her by the right hand and the other by the left, they

turned and took her slowly, slowly to the right, as if they were taking a young

child learning to walk… [Note: Here is one of the few times that Baron Nahabed finishes his sentence with the ‘hallmark’

expression of many Sepastatis, ‘gor’]…

and moved into the distance. Moments

later, from amidst the crowd, my two sisters and my mother came into view. I cried out, ‘Mother, Mother, look, look! The gendarme took Tshkouhi

from my hands and gave her to the Arabs!

Look, they took her away.’

“‘Aman,

mercy… I am struggling with my tortured soul.

What can I do?’ ” my Mother said with a final,

desperate resignation.

“When

we joined the group again we saw the exiles were now

surrounded by guards, bahaban,

mounted police and native Arabs. It

seemed then that a new soul or spirit, nor

hoki egav, came upon her. She began to cry, “

‘My Tshkouhi, my Tshkouhi.’

”

“It

was the last we saw of my little sister.

What was to be the fate [literally what was written on her forehead] of

my dear little sister? Into what kind of

peoples’ hands had she fallen, what kinds of trials and tribulations would she

endure? Would she grow up and marry a

Muslim? Would she turn Muslim and have

Muslim children? And lose knowledge of

her Armenian birth and language in her new life? I imagined and wondered all these things. I

still yearn that this happened [and that she was not killed.]

Rakka, My Mother’s Death

[It seems

appropriate to insert and include several maps of the region that show places

along the Euphrates River and the situation of Rakka, Aleppo

and Der Zor]

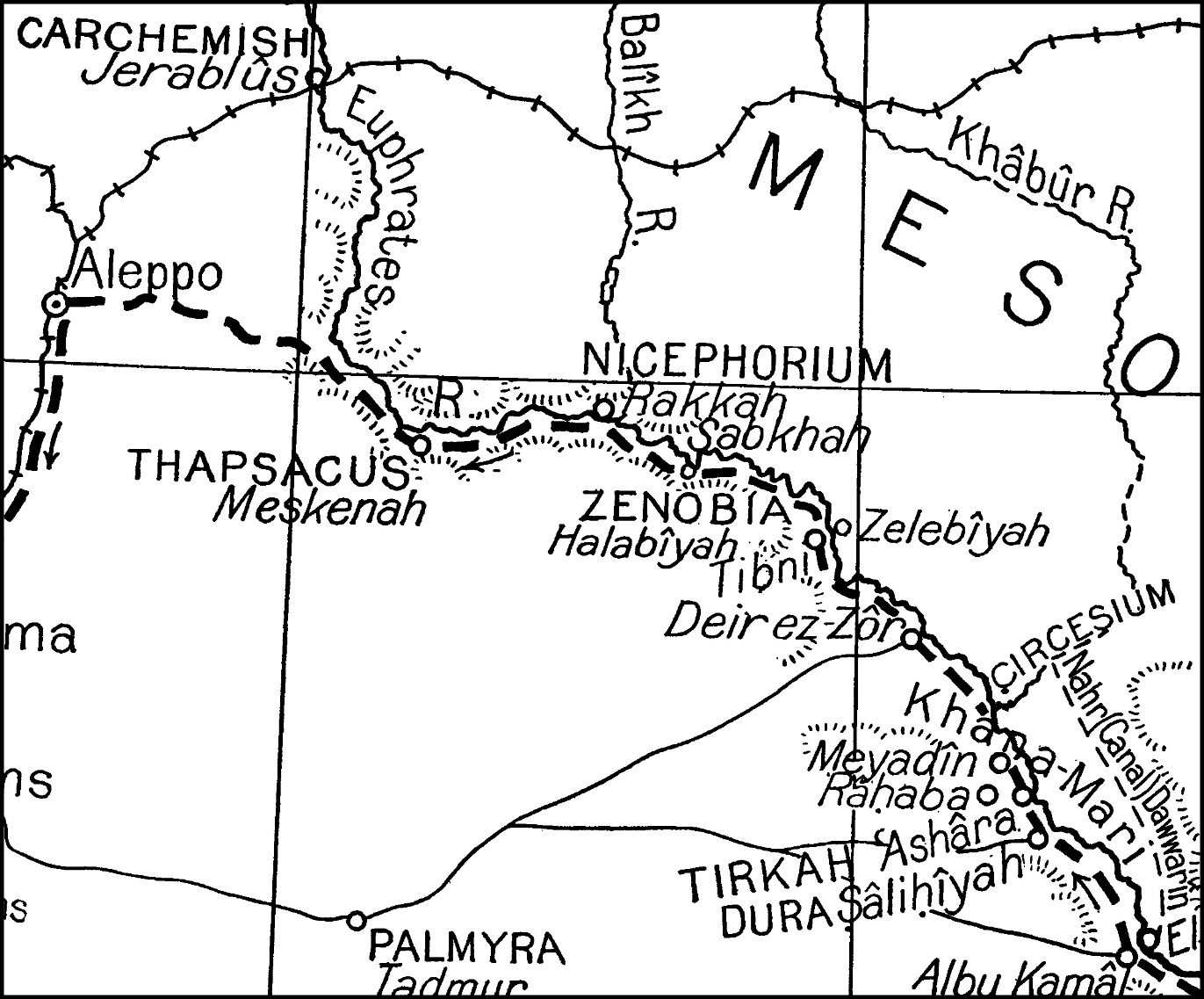

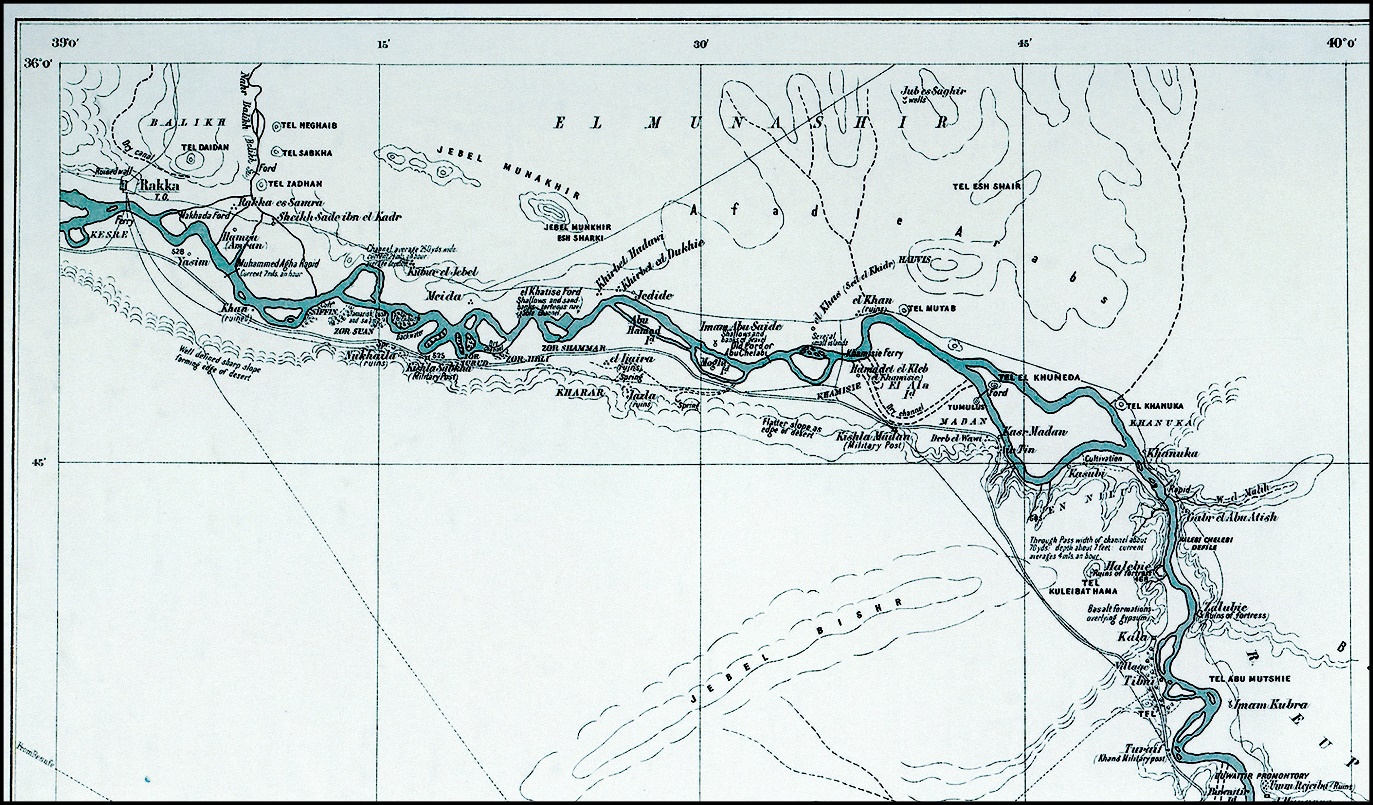

Fig.

1.

Enlargement

from a map of

Western

Asia from the Persian Gulf to the Mediterranean

showing

the route of the University of Chicago Expedition of 1920.

From

“James Henry Breasted, 1924” pg. 47.

James Henry Breasted

(1865-1935) did an immense amount of work on the region for the University of

Chicago. See especially “Pioneers to the Best American Archaeologists in the

Middle East 1919-1920”, ed. by Geoff Emberling.

The Oriental Museum Publication Number 30. The Oriental Institute of the

University of Chicago.

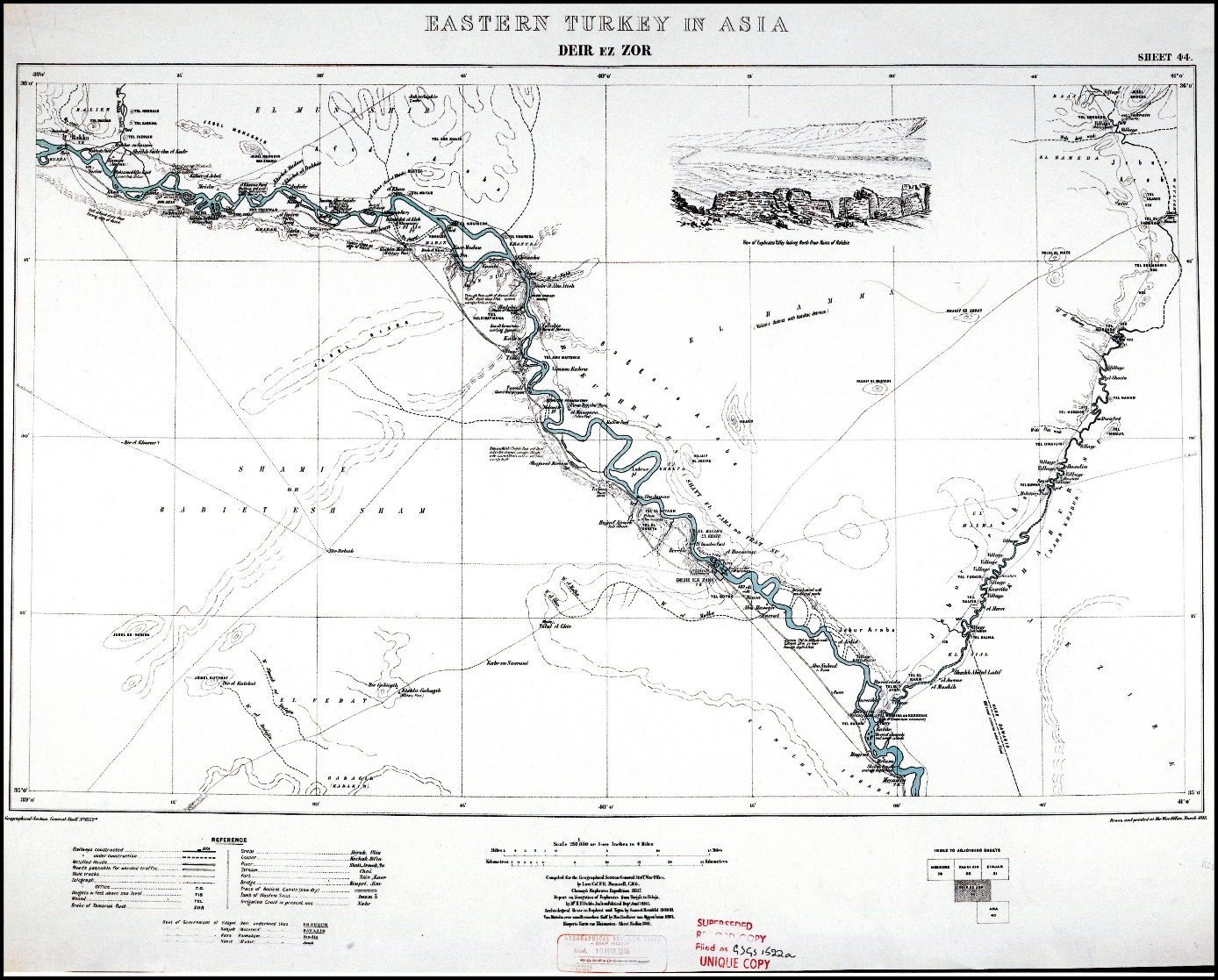

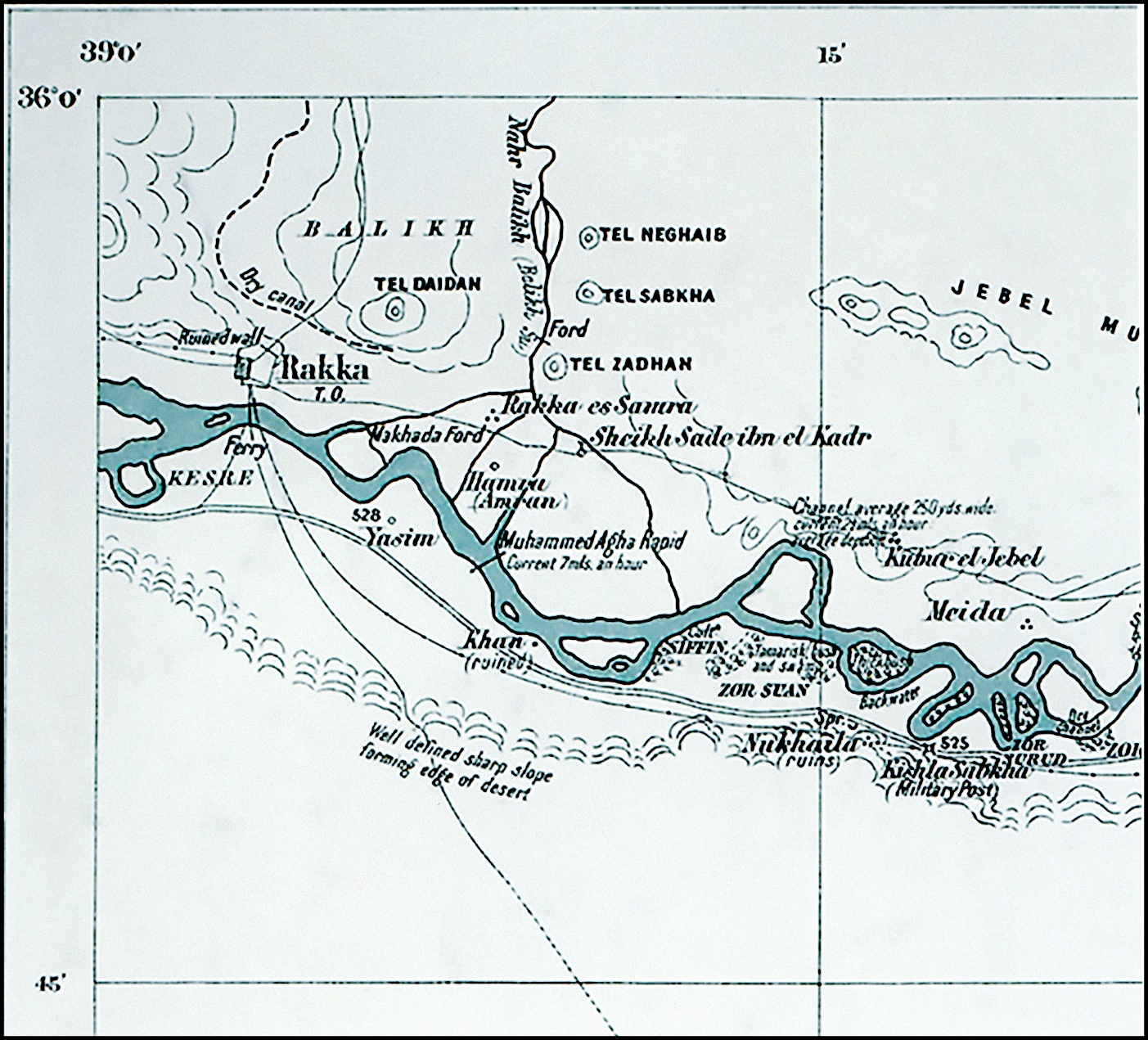

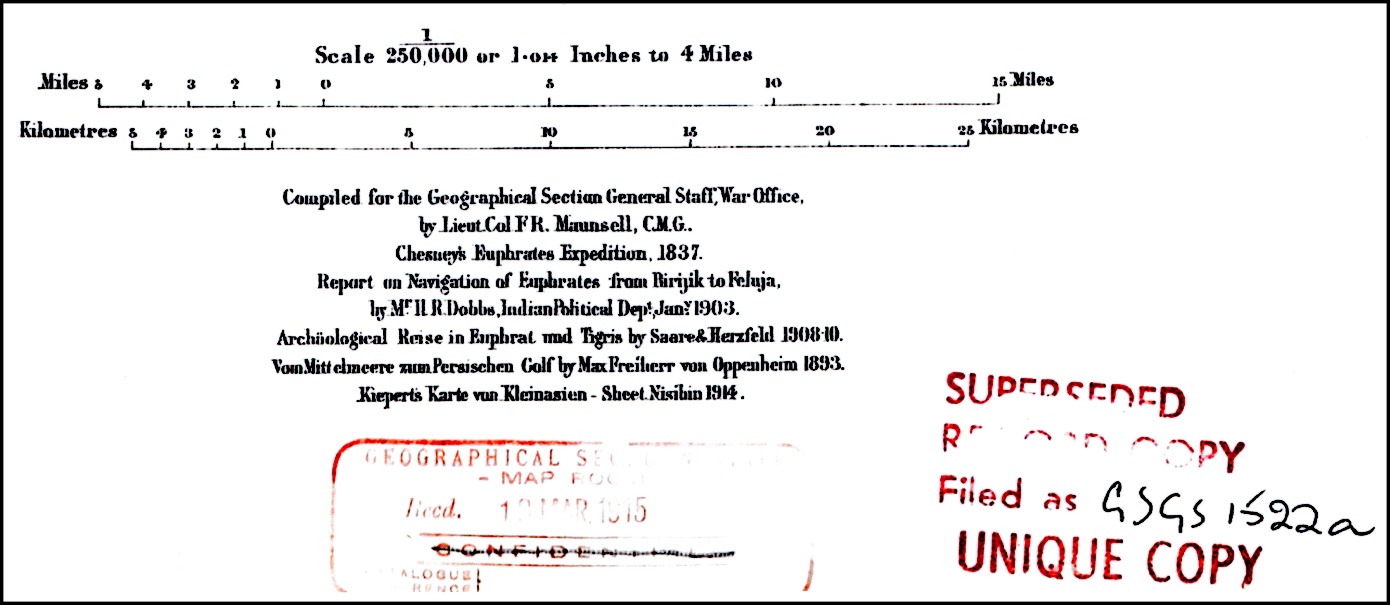

Fig. 2.

Full page reproduction of a

map of Eastern Turkey in Asia, Map sheet number 44 of Deir ez

Zor.

From”Maps of the

Ottoman Empire. Eastern Turkey in Asia. Sheet 44. Deir ez

Zor. Publisher: London: British War Office. Scale

1:250,000,

compiled by Intelligence Division War Office by Major F.R. Maunsell; derived from multiple expeditions 1839-1906.

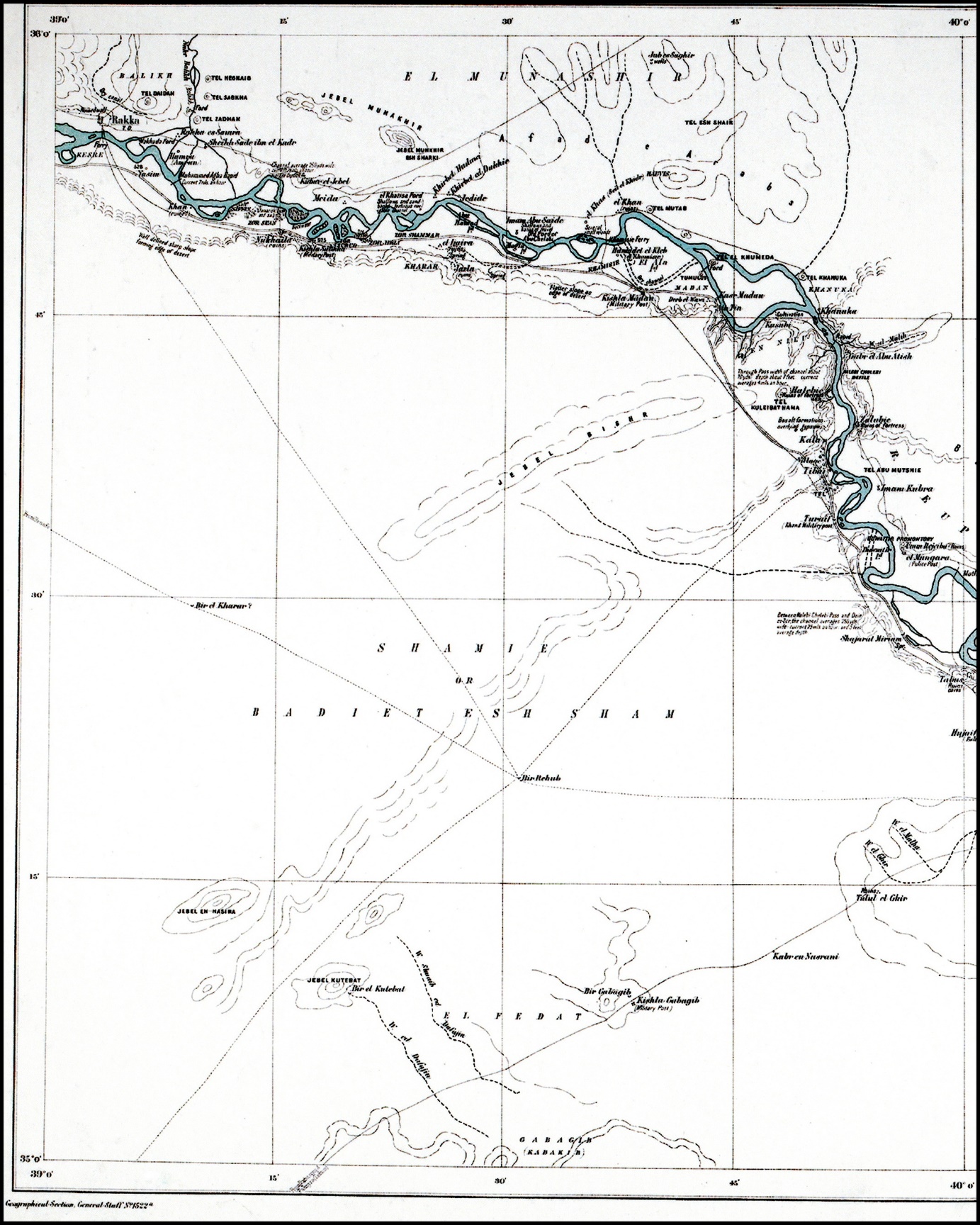

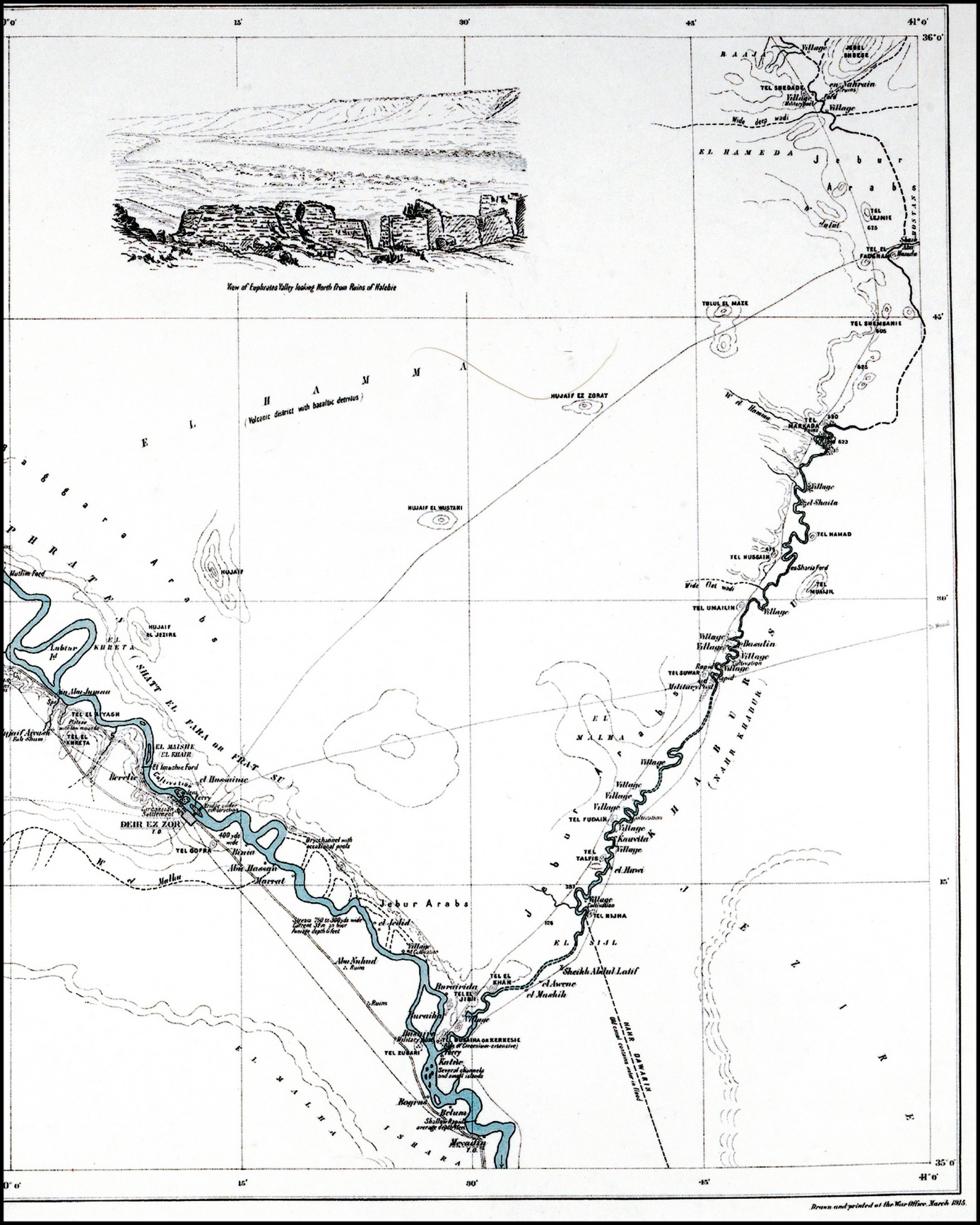

Because the map is large and the page size relatively small (Fig.

2), making it difficult to examine, we have included an enlargement of the left hand side of the map (Fig. 3) and the right hand side

(Fig. 4)

Fig.

3.

Fig.

4.

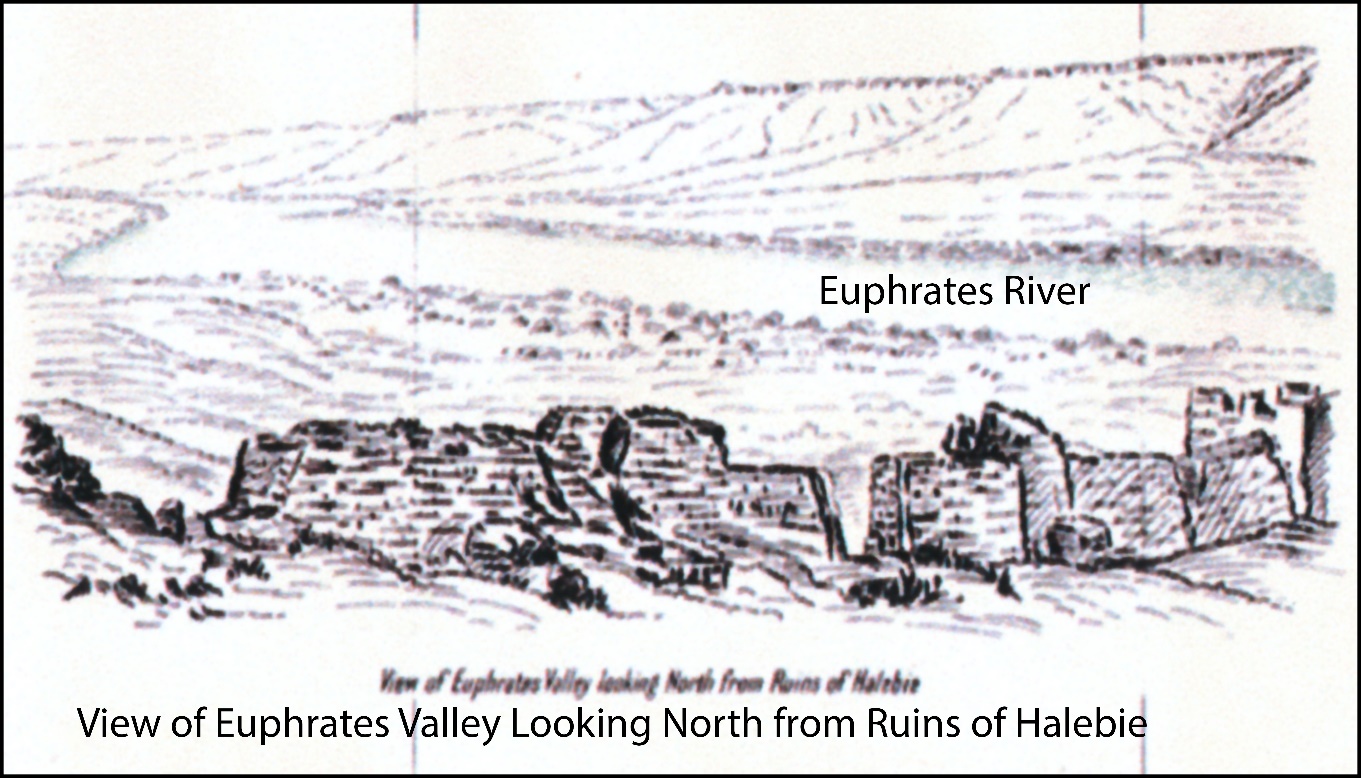

Fig. 5.

Still further enlargement of map (Fig. 2)

starting with Rakka on the upper left to

area below Halebie.

(For the view of the Euphrates Valley North from Halebie see Fig. 7 below.)

Fig.

6.

Enlargement of map to show Rakka especially – see at approximately 9 o’clock.

Fig.

7.

View of the Euphrates looking North from the ruins of Halebie.

This is an enlargement from Fig. 4.

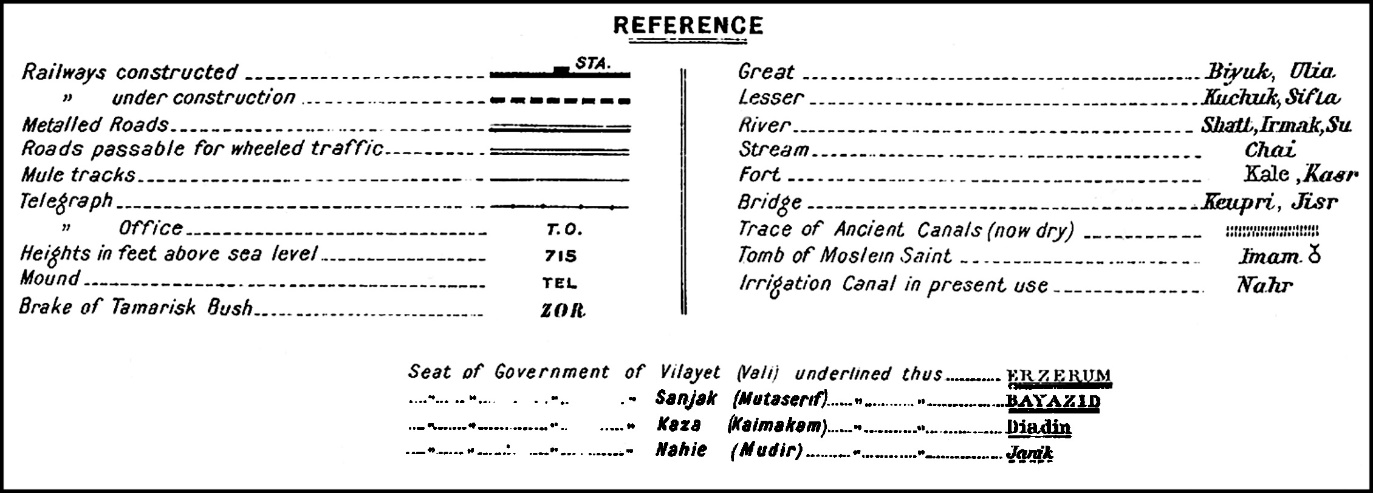

Fig.

8.

Fig. 8 is a Key for Figs. 2, 3, 4, 5 and 6.

Fig.

9.

Enlargement of the Library stamp providing information on the

sources for the Deir ez Zor

maps that we have copied and provided

for examination.

Four

days later, we reached Rakka city and the

deportees settled near the shore of the Euphrates River, Yeprad kedi yezerki. We stayed three or four days. We could go to the city to shop if one had

money to spend. And, even though I say

“city”, kaghak,

it now really was more of a small town rather than a village, but it consisted

of once grand houses. Years earlier it

apparently was a rather important ‘royal’ city but it seems later that either

Armenians or Assyrians, Assori, had settled there. We stayed three days on the sand, avazi vrah of the

riverbank. [Note: Baron Nahabed said three or four

days above].

“On

the third day my Mother died, mahatsav. I don’t have the will to describe it in great

detail since even after all these years, each time I remember, I am seized with

intense grief, sastig guh huzvihm. Amongst

the Sebastia group settled on the banks were

Gypsies. [Note: the

Armenian word kunchou

is used rather than the Turkish word chingeneh or posha]. They were

uncouth, ignorant and quarrelsome, gurvazan. In fear of them we didn’t say anything about

my Mother because, had they known, imanayin, they certainly would have taken the body from our hands and

thrown her into the Euphrates. Early the

next morning my two sisters and I dug, as well as we could, a hole in the sand

and buried her. The same evening the

local dogs from the scent uncovered the body, ate her, leaving only the

bones. We gathered these remains and

threw them into the Yeprad,

Euphrates. In that way my poor Mother’s

sorrows and pains finally came to an end—a remorseless fate, ankhuij jagadakir!

Hunger in

the Desert

“The following day half the deportees on the road were

moved, we among them. After ten days our

group now included Zeytountsik, people

from Zeytoun, people from Sebastia,

and others from a variety,

darpehr, darpehr, of

villages. There were thirty-five women

and three young adolescents, badaniner,

[a rather archaic term], from our own village, I was one of them. They divided the group into subgroups near the

Yeprad

River where they had constructed enclosed and covered pits, poser, in the sand into which one could

barely enter, haziv gurnayr mudnel. [Note:

It is not easy to picture this pos

precisely. It seems that it be best

likened to a moat-like ditch which has been somehow covered,

and has an entryway. It must have

been closer to a smallish trench, as in trench warfare?] So narrow, that only by leaving the door open

could 30 to 35 people be crowded into that close space--sleeping, crowded, sirar khirgadz, literally hugging, packed next to

one another, feet to feet. In the

daytime, we passed the day begging. They

distributed about five pounds of flour to each of us [Note: he uses the English

word “pound” here]. The following month

it was the same. Five pounds of flour

was gone within two weeks; we then had to go to the Arabs in the desert and

beg. For two months we were given the

flour, after that, there was none to be obtained other than by begging. In the morning at sunrise

we went into the desert where the Arabs lived under their tents, vuranneru dag, begging

for food until sunset. For our efforts I

have to say that one might be able to get a bit of millet, goreg, or spoonful of flour. Not to depreciate the amount given, there

would be over 150 people each day standing outside a tent begging. That situation was not just for a short

period, one day, or one week, or one month but lasted months—three months!

A Donkey in its Death Throes

One day, early in the morning, I was on my way towards the

deserts [again, Nahabed uses the word for desert, anabad, in its plural form anabadneruh]. I came to a place where I could see five or

six tents. As I neared, about twenty

feet away I saw a donkey, lying down near death [Note: Nahabed

uses the expression satgeloo

vrah eh; satgel is

generally applied to animals not humans].

I approached and sat near him like a hungry wolf waiting for him to

die. As long as he was alive the owner

was not

going to allow anyone to devour him, vorshadehn. I saw the

hour, endless hours, and the poor animal wouldn’t give up his soul and

die. There I was, seated at its head,

until his last breath. He finally

settled back with a gasp and a jerk.

Only then did I realize I had nothing other than my teeth, adamneruss, with

which to butcher him, usadeloo. I had to return to our foxes’ lair… [Note, mehr aghvesee orchuh; aghvess=fox; vorch=lair] …and

announce

that good news. I

was certain from that moment it was not going to remain unnoticed. I ran back towards our lair. Breathlessly I whispered the good news into

the ear of my sister, and she in turn whispered to our other sister; soon

everybody realized something unexpected, anagngal, had happened.

This was especially so since my sister was looking for something like a

knife. Everyone got up and ran after us.

I, in front, my two sisters behind. We

reached the place and like beasts, qazaneru numan, shortly, within ten to fifteen minutes that body, marminuh, of

the dead donkey had been butchered and cut into pieces.

My Aunt’s Death

“We

went back. A few days later my Aunt closed her beautiful eyes for the last time. We buried her body in the sands of Arabia

close to our ‘lair’ where we lived. What

kind of a tragic fate! [Note: again he uses jagadaqir,

literally signifying ‘writing on the forehead.]

She never had children; she dedicated herself to the children of her

sister. She was kind, unusually

beautiful and lovable. She was born in Kharaboghaz, grew up in Alaksa,

and married at a very early age in the flower of her youth [Note: read rather

rapidly as if reciting a hagiody]. Here in Arabia, Arabio metch, in the deserts she was to close

her beautiful eyes… her heart of gold.

Bid rest and peace, khaghaghoutiun, to

your tortured body, my sweet, noble, azniv, beautiful Aunt.

Peace upon your tortured sufferings.

What a troubled world, darabial ashkharh! Her

Mother-- my Grandmother-- we lost when we left her

under a tree in Divrig. Her husband was torturously killed, and her

dear sister, my Mother, became food for beasts. And she, here in the depths of Arabia, sealed

her beautiful eyes in suffering. Rest

and peace upon you, my dear Aunt, your suffering and

trials are at an end.

End of Tape

I, side 1, Turn tape over to continue

Note:

Although end of side one of Tape one was cut off, he apparently backed-up on

the other side, realizing that he might have lost some narration. Nothing is

lost.

A

Thieving Guide

“Now,

for more than four months we had been moving here and there without a home,

without the head of a household, anderagan, and kept here in the Arabian desert, begging.

“A

week after my Aunt’s death, the women decided, voroshel, that we return to Rakka. We had reached that unfamiliar place, the

Headquarters of the Gendarmes [Note: the Gendarmerie

were the Para-military police of the Empire], and under the escort of

gendarmes. In what way did this decision

get made? But everyone knows female

stubbornness, hamarutiunuh,

and evidently it was the cause of it.

[Note: it hard to comprehend how the women could have ‘decided’ on their

own to go to anywhere since they were under ‘escort’. One wishes that Baron Nahabed

had more precisely explained the situation.]

A day later, they found an Arab who spoke a little Turkish; he was

barely intelligible. He was to be our

leader, arachnort, to Rakka.

“Early

the next the morning we got on the road under the leadership of that rascal, surigal. The weather was cloudy and dreary. After one or two hours on the road, he

stopped short, saying, ‘para, para,’ money, money, mousareer,

mousareer (in Arabic), demanding money, all

the while rubbing the fingers of his right hand. The women put together a small amount and

gave it to the rascal. That day, as we

traveled drearily, with feelings as dreary as the weather, that rascal halted

ten to fifteen times until late at night demanding money. Early in the morning

before we moved on again, an elder, a bearded Arab introduced himself as the

authority, mukhtar, of that region, shurchan. The women prostrated themselves, kissing his

feet and hands and, crying, told him the story of their disaster. Appearing kind and sympathetic, he turned to

that rascal guide, and read him the riot act in a stern voice, khisd tsayn ovmuh, although we didn’t understand a word. The rascal, reddening, took flight, khuysiguh turav. The Arab, turning to the women, calmly told

them not to worry, that no evil would befall them again. ‘I will send my children to guide you all the

way to the city. May God be with

you.’ Saying this, he left. Shortly, two young boys came to serve as our

guides. A light rain had begun, and

after getting on the road, we reached Rakka by

the next afternoon, the place where four and a half months earlier we had

dwelled in the desert.

Rakka

We

saw that the tiny city had changed substantially. In that short time, much construction had

occurred. Before, there were only one or

two stores, khanut; now twelve. One oven for baking bread, now three. Four nuravajar shops [nur means pomegranate; vajar means merchant or

seller. Whether the word was generically

used for any kind of fruit not known.]

One pakalavaji,

seller of paklava.

One shop for tel khadeyif, two

tailors, and two shoe shops. The whole

central street of the place had changed, filled with newly arrived Armenian

exiles from many places. We paused in

front of an Armenian tailor shop opposite a government building. The two brother guides, having finished their

business fully [Note: use of the archaic word liuli], turned and left.

“Half the day had passed chilly, now it turned cold and began to rain. We were trembling. “Allah ashkinah”, [meaning “Dear God”-in Turkish; normally an Armenian might say, Asdvadz vehrehn var etchir, “God, please come down from above!] The women and we three boys were crying. Minutes later, out of the government building, descended a zaptieh [a Turkish policeman, pronounced by Nahabed as zaptiah]. He looked at us, turned, and went back in. He was followed by a young man, who announced haughtily, gorozapar, ‘My name is Nishan. Follow me.’

“We walked in the heavy rain, leaving that heartless place, reaching an open space surrounded only by four walls that now served as a public toilet, artouarzart by the city folk. ‘Stay here,’ he said and disappeared, anhaydatsav. This was no place to stay. The stench was terrible. We couldn’t remain there breathing that horrible smell. Crying and moaning, voghpalov, we returned to the front of the government building. A zaptieh [Turkish policeman, again pronounced zaptiah] emerged, saw our lamentable lot, said ‘Vagh, Allahan, vagh’…[all in Turkish, but Baron Nahabed repeats the Turkish in Armenian] ‘Dear, dear, Good God, dear, dear! What sort of a lot is this? Follow me!’

“Stepping into the city street, we turned right and paused in front of a door. Two soldiers, zinvorhr, came to join him. They opened the door and we saw twelve camels. He directed the soldiers to remove them and took us all inside. ‘Now wait here and I’ll be back.’ He returned shortly with the soldiers who carried two baskets, goghovnerov, of warm bread, fresh from the oven. They distributed two to each of us and said we could stay until further decision, voroshoumn, from the authorities. That place was for us like Paradise, Trakhd, spacious, layn, and warm. I had not eaten bread for over four months. At first, the bread remained in my throat, gogort, and I seemed to choke on it. We stayed here for almost three months.

Forty Thousand Exiles on the Road to Der Zor

“Each morning, while there, we would go to the deserts to find fuel, varelaniut, for the ovens. In the afternoon, we returned to the city with the load, pernerov. They brought us all one or two loaves of bread in return. One morning we went to the desert as usual, and as we were returning towards the city with our loads, we saw both sides of the road lined with soldiers, four by four, pasharvadz chors, chors. They took our fuel, gave us each one or two loaves of bread, and led us to the banks of the Euphrates River where thousands of exiled people were waiting. Within an hour or two, all the exiles found there, were moved to the right side of the Euphrates.

“Several

hours later, in that multitude, ayd pasmutyunin mech, we found my two aunts, horakuirs—father’s

sisters and Gulizar, the daughter of one of my

aunts! We waited several days as other

exiles arrived joining our group. Four

days later forty thousand exiles were on the road toward Der Zor.

We

reached Der Zor after traveling two weeks. Here, to give a more detailed picture of our

travel on the road to Der Zor, I am stubborn and will

say no more. I will only say that we

didn’t enter the city; we passed by on the outskirts, al yezerken antsank. At Der Zor there,

the Euphrates River divides in two. [Note: I think this is incorrect. It needs to be checked on a period map since

the course and dimensions of the river have changed.] The exiles settled in the desert some two

miles distant from the river. We stayed

there three days. Amidst the 40,000

exiles, only some seven or eight thousand had tents for protection from the sun. The rest were scattered throughout the

desert.

After

Easter we were set on the road again. [How did they know the dates and Holy

Days?] The crowd began to sing. [Mostly Turkish words of the song recited

here but not translated into Armenian—the only words I can figure out are Zadig, Easter and chadrr,

tent—I have consulted Dr. Verjine Svazlian’s

“The Armenian Genocide in the Memoirs and Turkish-language Songs of the

Eye-witness Survivors” Yerevan, 1999, but have found nothing suggestive.]

Towards Baghdad with a New Leader

“Now

I only remember this much. We were going

to Baghdad. The heat of the Der Zor Arabian desert was unbearable, andaneli, especially for the

physically weak. After a week on the

road we reached Mudurluk

[mudurlukmi, Baron Nahabed

explains, bashdonagan kiughmi,

literally a functionary town - perhaps more properly a regional government

center]… and there for three days in the desert we rested, tatar. They distributed some flour to us. On the fourth day, they put us on the road

again. But things were different. The head gendarme was a 30-35

year old good-looking, tall, partsr hasagov, man.

Before

the sun had barely risen, he would get the exiles on the road, and by ten or

ten-thirty when the sun was unbearable, he would find a spring, aghpiur, or a

place with a stream, arvag

for a place to rest. I want to stress, vor sheshdem,

this because it is very important: We had traveled twenty days under this man’s

leadership. He had beaten sixteen Arabs

to death [?] who tried to rape, purnaparel, women or girls or kidnap, arevankel, children or to beat, dzedzelou, or otherwise attempted to rob, goghoptelu, or

put a person through an ordeal or take to task, ports arelu.

“Two

other incidents are imprinted in my mind, still clear. The first, on one day late in the afternoon

when stopping near the riverbank, we saw Arab women, Arabouhiner,

and men, Arabner, wandering among the

exiles. The Arab women, freely speaking,

ariman khoselov,

were there for the purpose, midumo,v of selling bread, hahtz and tan, diluted

yoghurt, but the males, dughamarti, came with another purpose.

“Suddenly

we heard a woman scream. The women and a

few lads like myself ran in that direction and saw an Arab, twenty-five to

thirty years old, pulling by her arm -- an eight or ten year

old blonde-haired girl from the hands of her mother. The head gendarme came in time with three

helpers. They grabbed the Arab, and presented him to the leader who took him to the

edge of the stream, pulled off his white shirt, shabik, completely undressing

him, bolor mergatsutsin. They tied his feet and hands and whipped

him. With every blow, harvadz, he

furiously demanded in Turkish ‘Ermeni?…[not intelligible to me, other

than the query pertaining to the Armenians, Ermeni?] Beaten in this way, the breath was taken out

of him, shi’nchanatz hanets.

Witness to yet Another Tragic Sight

“On

another day a disturbance occurred, araq muh badahedtsav. It remains deep in my heart. We were settled on the banks of the

river. It was afternoon when uproar, aghmugmi, broke

out; the attention of the people turned to where it was happening. We saw a woman, about forty or fifty years

old, her mouth bloody, lying trapped in the swift current with a donkey, his

tail in her hand. [Nahabed

uses the Turkish word for donkey, ishoun, from the esh or donkey], aboreli arartimi metch, niuyn avanagihn

hed.

Gulizar Has a Plan

“Twenty days further on the road as we followed the

curving river bank, we settled and rested. On the third day I saw my sister Gulizar whispering with a woman about the same age, hasagagits, from

our village. With the curiosity of a

young kid, yerakhayutian

hedakurkirants,

I began to listen. They were planning to

go to the desert to beg among the Arabs.

They stood up, wandering off like the [Arab] women who would come and

stroll among the deportees, and thus they distanced themselves. How many times did my sister turn around and

try to make me go back? But, I stubbornly persisted, following at a distance, and

after we had gone quite away from the caravan she coolly relented. One hour later, passing a hilly area, we lost

the deportees from our view. From a

distance we saw ten or twelve tents in the desert and headed towards them. From the first tent we reached, a young man

emerged. He examined us coolly and

signaled us to go inside. With her hand

our female companion warned us to back off.

But we went ahead and that was the last we saw of her.

“His

elderly mother was seated under the tent scrutinizing us closely. It was near sunset. When we tried to leave the tent, she prevented us with a hand movement, and said some things,

none of which we understood. We spent

the night, with heavy heart, in the tent.

Next morning another Arab woman, about forty years old, came. From her appearance, the way she was dressed

and the respect she was given, it was apparent she was the wife, dirouhi, of

the chief of those tents. The young

fellow and his mother showed her much deference and attention. They did not appear to contradict whatever

she was saying. We were unable to

understand one word. From her actions and attitude it

became apparent that she wanted to take my sister with her. I began to really cry. She gave me a careful look, and the same to

my sister, but it was clear. She turned

to speak to the old woman and her son; they listened with heads bowed. Turning to my sister and me, she signed for

us to follow her.

“Now,

I cannot remember her name, and I hurt very much over that. From seven in the morning

I would take the lambs, garmougneruh

to pasture, arod. The first week she came with me. After staying for about half an hour, she

went back to the tent. At nine thirty or

ten I would hear her calling, ‘Hehd, Ali, hehd! Here, Ali, Here!’ They had given me the name Ali. She would come and take me back to the

tent. ‘Nam, Ali, nam’ she would say. She would take her hands and place them on

her face to indicate that she meant me to sleep. [Note: Baron Nahabed

says nap, instead of nam. It is clearly a slip of the tongue.] She would say ‘Ali, rest and take a sleep.’

She took care of me like a, harazad, mother or grandmother. I will never forget that when I began to

count from one to ten in Arabic she was as happy and proud as a grandmother

whose grandchild, tornig, had taken the first steps in walking

or first syllables, vanguh. She enjoyed every correct word I learned in

Arabic and left the tent to tell the other Arab women. I want to offer my gratitude and respect to

her and her family. Even though I have,

unfortunately, forgotten their names, I will never forget the way they treated

me and will always be forever grateful.

An Important Change

“We remained about five weeks at that place. Later her two sons, zavagneruh, came and made

preparations to move all the sheep and goats, and all else needed, to be

integrated into their own group. As luck

would have it, the village where we had gone to beg was located on the left

bank of the river and the exiles were now settled on the opposite side. After having taken care of all the

preparations, the older son took me on his back, and swimming, we crossed to

the left side. The following day, the

remainder of the people came, bringing my sister, Gulizar,

with them.

That

family was the head family of Shoun [?] village

[sounds like shoun kiuighi]. They had three male offspring, two married,

the youngest still a bachelor, amouri. Our family’s

Village Headman, Kiughaderuh,

ten or twelve years older than his wife, was kind, respectful, and worthy of

her. He gave me the business of grazing

the lambs in their summer pastures, yaila, summer dwelling place, [note from the designation yaila it is clear

that these were nomadic or semi-nomadic Arabs].

We Leave

“The sun was setting and we had been away from the

village for a month at several yaila-s, summer

pastures. When I returned with the

lambs, my sister whispered to me that a gendarme, accompanied by a military

physician, had come to say if we wanted to leave with them

they could take us to Shaddadieh. They added that if there were other Armenians

in the area who wished to come with us, they would kindly take them as

well. My sister believed them. In that area there were five or six Armenian

adolescents. I explained the situation

to them. Five of them agreed to come in

a half hour to join us. But when the

time came to get on the road, not one of them showed up. In the evening at six o’clock we started on

the road. Neither the head of the

household or anyone in the family opened their mouths to say a word.

“The guides on their horses and

we walking, reached Shaddadiyeh

in six and a half hours. We were

barefoot, bobig,

in the desert picking up thorns and prickles, poushereh, from the bushes on our feet. There were some thirty or thirty-five houses

but that night we saw nothing –everything was dark and obscure, mut yev khavar. After

passing a dry canyon, tsor,

we soon saw high on a hill, the light of candles glowing from a government

building. We reached it.

“Now,

you see, they already knew about the time of our arrival. A fifty to fifty- five

year-old man came out with a servant and beckoned his two guests to

enter, directed us to the attention of another servant and left to join his

guests. The servant, holding a candle,

signaled us to follow him. We were led

to a tiny cell, khoutsmuh,

[pronounced ‘koohtsmuh’] bare and only covered

with a mat, khusir. ‘Sleep here tonight,’ he said roughly and

went out leaving us in the dark.

“Thirsty,

hungry and exhausted, we lay down on the floor of the cell and in a few moments we were in the world of dreams. When we awoke in the morning

we saw sunshine through the narrow window.

Minutes passed. What were we to

do? Then, a nine or

ten year old boy came introducing himself in Armenian as Hagop. The master, Efendi, had instructed him to take us to

his [i.e. Hagop’s] sister’s

where she was to feed us. We followed

him entering a clean kitchen, makour khoharanotsmuh, where his sister, smiling, introduced

herself as Untziag…[not

absolutely sure if it is –Utsiah or Utsiag, or Untsiah, etc. but

U[n]tzag—signifying tiger or leopard, is a girl’s

name, albeit uncommon] … She gave no last name.

“‘We are Urfatsis’ ” [from the city of

Urfa] she said with a smile on her face, zhup’d eress.

She added that seven or eight months earlier Baron Mudur [I cannot be sure of the name yet since in Turkish

the word mudur