Armenian News Network / Groong

EVOLUTION OF A GRUESOME PHOTO OF DECAPITATION:

From Instilling Terror to

Typifying Turkish Savagery

Armenian

News Network / Groong

June 3, 2021

Special to

Groong by Abraham D. Krikorian and Eugene L. Taylor

Long Island,

NY

In 2010 we published a lengthy essay entitled “Achieving Ever-Greater Precision in Attestation and Attribution of Genocide Photographs” (see A.D. Krikorian and E.L. Taylor, 2010). In it we stressed a number of important points – first and foremost the difficulty of determining accurately what a “genocide photograph” represents (attestation), and its attribution (that is identifying a photo with a place, time and even person.)

We also drew attention to the possible consequences associated with careless misidentification that could be loudly voiced, actually ‘flogged to death’ so to speak by those like ‘the Turks’ who inevitably nominally see themselves falsely accused of barbaric behavior and crimes through presentation of incorrect facts. According to them, it is all propaganda. On very rare occasions ‘the Turks’ concede a miniscule bit, usually on some unimportant point, but they end up saying that those presenting such blatant tripe are never well-meant and the expositors clearly don’t know what they are talking about – at ALL levels. In a word, rotten ‘scholarship’ at ALL levels. (We shall interject here that apparently the Turkish establishment persists in believing that incessantly drawing attention to these same few mistakes in imagery will distract the Turkish populace from the reality that its predecessor Ottoman government committed genocide. Various, usually very obtuse and nonsensical arguments are made to claim and sustain that there was no genocide. These arguments have long been institutionalized and range from putting forward ridiculous arguments that there could not have been a genocide since the word was not yet invented, progressing all the way to ‘there was no genocide but if there was, the Armenians brought it on themselves!’

‘The Turks’ have been very protective of their self-constructed image, and anything that is interpretable as challenging their version of it, is mercilessly shredded. Many would say “Rightly so! It is an author’s responsibility to get things as correct as possible or at least correct enough to not use obvious fake photos that are sure to be found out and exposed. (Again, ‘the Turks’ believe that it will not emerge and be obvious that they themselves do not practice what they preach. Even as they supposedly deplore and ridicule the errors of others, they studiously cover up or ignore their own blunders. There is also the not so minor tactic of genocide denialists using trumped-up fake scenarios wherein murdered Armenians are displayed in photos as Muslims victimized by Armenians!). A classic in that category is described by el-Ghuseyn in his work Martyred Armenia (1917, 1918).

It seems forever in our memories that the reality and

veracity of this authoritative report by an Ottoman official and Bedouin

Notable of Damascus has been cast aside. Even the existence of the person Faiz el-Ghuseyn who wrote it was

doubted by the pro-Turkish side. The fact is that the author and the report are

all-too-real and this report is graphically very

telling. Nothing is contrived or fake. https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Martyred_Armenia

Even so, we are still supposed to

believe that Turks and the supporters of their point of view are paragons of

disinterested, objective researchers, impeccably honest and honorable in their

‘scholarship.’ In fact, a rather good case can be made that among the genocide

deniers are non-Turks who have made a bit of a reputation in promulgating the

notion that all ‘these incriminating documents’ are fake! We shall spare the

reader by not giving their names or delving into the reasons why they do so.

Books have been written on the topic. One obvious fact that emerges from even

superficial studies is that this work is not done by objective academics. Quite

the opposite. There are indeed a few remarkably principled and forthright

Turkish writers, but the overwhelming tendency is to publish in venues that

will not attract undue attention from government officials.

Below we give another example of

yet another category of deception and tactic that was followed by the Turks.

These tactics were followed rather early on. This is a quote from a virtually

unknown letter written by a relief worker from the Smith College Group (a 1901

graduate of the College) Esther Follansbee Greene,1879-1968, to her mother

dated Sept. 8, 1919.

“If I look out of the window to the North I see smoke rising over a deep green shallow valley of trees which is old Malatia. A week ago Mr. & Mrs. Miller, publicity people, went over there to see a pile of skeletons of five thousand Armenians killed on the roads around here. They were quickly gathered up and partially burned when the Americans were coming. They took some pictures and evidently frightened the Turks, who wished to wipe out any signs of the massacres. That night some girls came out on the porch where I was sleeping and excitedly pointed out a glowing fire and told me what it was. It may have been the bones of their own parents burning. I don’t know what they do to make them burn, evidently build brush fires over the heaps., but they have been smoldering a week. Also two other places not far off are being destroyed so that we cannot use them for testimony.” (Taken from our Research Notebooks: Readers interested in the Smith College group should refer to Laycock and Piana (2020).

While what we have just expressed is absolutely correct and eminently defensible, there is a nuance or dimension or refinement to that straightforward viewpoint that we will try to expand upon.

We have taken the trouble to post some papers on Groong that show how the use of photographs can rationally, legitimately and quite easily evolve and change in time from what was perhaps originally a quite different intent and purpose into yet another. This might take different stages and forms, but to us, a most conspicuous aspect that has surfaced and emerged from our studies is that this change or evolution can take place relatively quickly. The specifics on these relevant postings that will allow access follow.

The Power of a Photograph and Its Recycling Over Time, April 23, 2021 by Abraham D.

Krikorian and Eugene L. Taylor at https://www.groong.org/orig/ak-20210423.html.

Also see:

Adapting an Existing Work of Art for Use as a Fund-raising

Poster Simply by Adding Text, April 24, 2021 by Eugene L. Taylor and Abraham D. Krikorian at https://www.groong.org/orig/ak-20210424.html,

and

Poster Soliciting Funds to Support Armenians using Armenian

survivors of the genocide as Illustrative Models, April 25, 2021 by Eugene L.

Taylor and Abraham D. Krikorian at https://www.groong.org/orig/ak-20210425.html

What is stated in these postings should be very clear to any reader. We have tried to be direct and unambiguous about the messages contained therein. The long and short of it is that photography and imagery of all sorts and by its very nature for use is a very interpretative medium.

Nevertheless, in the course of re-addressing our attention to details covered in our initial necessarily lengthy 2010 essay on attestation and attribution and their inherent difficulties, we note that we devoted a fair amount of space to a specific problem that can emerge if one is too confident about what a photograph or bit of imagery might represent. The Groong postings cited above emphasize that strategies for use and actual use of photographs have routinely been, and even today are still constantly adjusting. Only the most extreme of purists might say that this is never legitimate. It is difficult to argue against the perspective that use of a given so-called ‘genocide photograph’ is more often than not politically motivated.

We devoted many pages in that 2010 essay on attestation and attribution to a painting completed in 1871 by a well-known Russian artist named Vasily Vereschagin. We related how a photo print of his painting was presented in 1980 as representing an actual photograph taken during the Armenian genocide period starting in 1915. The 1980 presentation in print was not the first time it was presented as ‘real.’ But the amount of embarrassment and furor this 1980 ‘nominally more modern’ blunder caused, and the detriment to the reputation of the German scholar who made the error is thought even today by some to be irreparable.

We are especially quick to point out here that the distinguished scholar who committed the error quite innocently promptly tried to make amends. Her apology and photo and text corrections and changes to new releases of the book did no good (see page 418 and following in our 2010 Krikorian and Taylor essay.) There was never any reason, of course, to think that it really would do any good. This is because pro-Turkish ‘armies’ of observers seem to routinely vet the literature to see that no harm is done to the Turkish image at large. The subject and contents of the volume with the offending photo was at great odds with the narrative promulgated by successive Turkish governments about Armenians and their so-called or fake genocide.

For our part, trying hard to be objective, we did our best to present a fair and balanced assessment of how such an error might well have been made by anyone who was not a specialist in images relating to the Armenian Genocide. We also should point out that even today we do not really know anyone who would or could qualify as an expert on this topic, especially if the bar is set appropriately high- as we believe it must be. (In our opinion. the field or discipline for such study, particularly in connection with the Armenian persecutions and genocide imagery is still waiting to really take hold and develop.) Against that fact is the situation that for many print specialists and historians, the viewpoint has never really been taken seriously that images matter. They are most often used to break up text and perhaps lighten reading. Anyone who doubts that statement is delusional in our opinion. At best, the user or author ends up being the primary, and often the only point of control, or of any editorial censorship. The same may be said about most imagery used today, and even video footage in newscasts or portrayals. One need only analyze or examine the use and re-use of the very same video footage for quite different presentations. In other words, this imagery is regularly reduced to generic status.

A sampling of why we say all this may be found in a work on photography, photographic meaning and interpretation in relation to intent that covers essentially all the important points of this kind of work and the expertise needed in analysis to achieve the fullest, and most accurate interpretation.

This now classic, highly original book entitled Photography Against the Grain: Essays and Photoworks, Halifax, 1984 and 2nd edition, London 2015) was published a number of years ago by Alan Sekula. It includes a full analysis of photography and has many new insights and perspectives. Even novel phrases like “traffic in photographs” and ‘passion photo projects’ which he used, have gone far to re-shape the terms under which relatively recent and contemporary photography is discussed and understood The long and short of it is that there is no end, and probably never will be, to justifiable and forthright discussion of such matters.????

The misuse of the original painting titled “The Apotheosis of War” by Vasily Vereschagin, mentioned earlier, caused a disastrous reaction in Turkey and among Turks and their supporters everywhere once it was gleefully brought to their attention. The painting is indeed a vivid and haunting scene, but at the same time it is an overwhelmingly depressing painting. It shows hundreds of skulls piled on top of each other, creating a pyramid. Vereschagin caustically dedicated the work “To all great conquerors past, present and to come.” This caustic indictment may be seen on the lower edge of the painting’s beautiful frame. (Anyone wishing to get an in-depth treatment on the Vereschagin painting which may be seen at the Tretyakov Gallery in Moscow may refer to https://figurementors.com/Theory%20Hubs/vasily-vereshchagin-nihilist-inside-the-apotheosis-of-war/)

In a vaguely similar, but assuredly not the same manner, we personally had an opportunity to get involved directly in a situation about a forged or faked ‘nominally Armenian Genocide’ photograph, which like the Vereschagin painting, had been used carelessly, again clearly unwittingly in more than a few places. One was in an important book written by Donald Bloxham from the University of Edinburgh and published by Oxford University Press in 2007. Bloxham indicted Ottoman Turkey severely and in no uncertain terms for the genocide of Christians in the Ottoman Empire. Unfortunately, a fake photo was erroneously presented as a valid photograph from the period of the Armenian Genocide. The fake had been assembled years earlier from several prints and reprinted as a single photograph.

We were hesitatingly dragged into the melee by friends

imploring us to ‘speak up’ in the hopes we could help resolve the various

issues surrounding this fake photo. They knew we had worked on it but had not

yet seen fit to elaborate upon it in print. This fake photo was being

speculated-upon left and right in a completely different context on

various social media venues. Many thought that the attention being devoted to

it was disproportionate to the level of the blunder. Others thought it was

indeed a grievous and egregious mistake. We and many others have said that

there is plenty of evidence that the Armenian Genocide was a genocide and that

no photograph is going to prove or disprove it.

Our research work aimed at delving into the facts yielded a

fair amount of detail on exactly how the image was indeed faked. We published

our findings on Groong. See:-The saga surrounding a forged photograph from

the era of the Armenian Genocide demonizing and vilifying a "cruel Turkish

official": a ‘part’ of "the rest of the story." February 22, 2010. By Abraham D. Krikorian and Eugene L.

Taylor. https://www.groong.org/orig/ak-20100222.html

Exactly why and specifically when the contrived photograph was used should be carefully studied of course. One can easily see why it was so predictably offensive to ‘The Turks’. The exact milieu in which the production of the fake was contrived and produced remains in our minds still very much up in the air. We can guess but it would only be an educated speculation. Rest assured that the Turkish aim has always been to deny and re-position the Armenian genocide in the world narrative - that is the narrative promulgated by Turkey. Photographs are merely one aspect of the strategies involved. Making the victim the problem is paramount.

Deception is not an archaic concept. It has been around for a very long time and we are not the first to predict that it will continue to be! When this ‘fake’ photo was probably being presented, the Armenians were still engaged in processing and reacting realistically but still not anywhere fully, to what has come to be called the Armenian Genocide. Similarly, recall the reality that working with public opinion was a well-established practice and had not escaped the attention of Turks or the minorities of their Empire during that time.

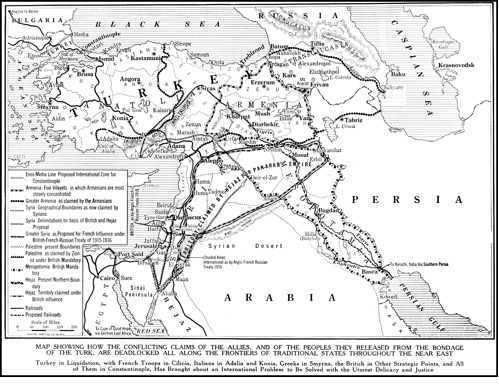

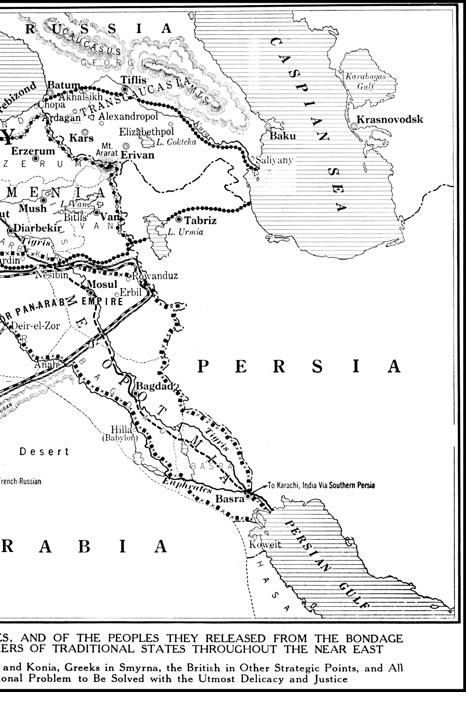

Figure 1a provides a map that gives a good idea of the problems and challenges facing Armenians and many others as a result of the anticipated termination of World War I and the collapse of the Ottoman Empire. To aid in reading the small type, we also present the map in two sections.

he first part of the caption reads:-“Map

Showing How the Conflicting Claims of the Allies, and of the Peoples They

Released from the Bondage of the Turk, are Deadlocked along the Frontiers of

the Traditional States Throughout the Near East.”

The latter part of the caption reads “Turkey

in Liquidation with French Troops in Cilicia, Italians in Adalia and Konia,

Greeks in Smyrna, the British in Other Strategic Points, and All of Them in

Constantinople, Has brought about an International Problem to be Solved with

the Utmost Delicacy and Justice”

Fig. 1a.

Fig.1a. shows the map in its entirety. Fig.1b. and Fig.1c. show the map broken up into 2 segments from left to right respectively to facilitate closer observation and study. Copied from pg. 1199 of Fleming, Jackson (1919) “Mandates for Turkish Territories.” Asia. The American Magazine of the Orient. Vol. 19, no. 12 pgs. 1195-1202.

Fig. 1b.

Fig. 1c.

We state here that so far as the Armenians were and are overwhelmingly still concerned, the key point has been that justice does not mean restoration of the intact past, but honest recognition. There never can be restoration of what has been destroyed. There was certainly a measure of overreach on the part of all parties involved as reflected by geographic and political partitions in this map, but that is apparently a normal, human reaction. The tragic fact was that the destruction of the Armenians of the Ottoman Empire had occurred, and as the Armenian villagers used to lament with resignation “Eghadz’uh egher’eh” – “what has happened, has happened.” Nothing can change that.

Armenians learned very early that one cannot change the past, any more than one can forget it.

We re-emphasized in that 2010

Groong posting that the reality of the Armenian and other late Ottoman

Genocides do not need visual affirmation to satisfy honest scholars. Historians

and all others with working minds and functioning grey matter who can analyze

facts, will know that the genocides were real, and

the term justified. We repeat that emphatically here.

One especially pertinent fact may be given. Raphael Lemkin, the eminent jurist and coiner of the word genocide, said in a February 13, 1949 TV broadcast that his ‘new’ word clearly applied to the Armenian case (see “Raphael Lemkin on the Genesis of the Concept Behind the Word "Genocide" by Eugene L. Taylor and Abraham D. Krikorian, Nov. 28, 2014. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CXliPhsI530

Certainly no one forced Lemkin to use the word genocide in the case of the Armenians,

but what the Turks did to the Armenians were fundamental to his thinking about

genocide. For an authoritative more

modern, up-to-date legal assessment on the appropriateness and applicability of

the word genocide see “Geoffrey Robertson, QC and Human

Rights Barrister Amal Clooney speaking on the Armenian Genocide at the European

Court of Human Rights in Strasbourg January 28, 2015” at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_eGYdC0uTr8.

Much effort has been gone through

to document rigorously and locate the Armenian genocide on the so-called

“Genocide Spectrum” by various scholars (Huttenbach,

1988). It is an important element for a number of

obvious reasons. Huttenbach tellingly states “…while the Turks did not explicitly say as

much, that is precisely why the Armenians were annihilated - because they were

Armenians.” (pg. 290).

The entire matter of fake or

forged photographs to embellish descriptions of the ‘Armenian’ genocide,

however, is a very different matter and essentially another story of course.

We shall start off here by saying that fake and contrived photos are nothing new.

Having expressed that

statement here in bold type, we know very well that it is important to admit

that in this day and age especially, imagery has

become paramount, and often even central

to the narrative regarding the genocides committed by the Ottoman Empire. This

is arguably so of course for all

genocides, not just those committed by Ottoman Turkey.

All that has been said so far is an introduction and background to what now follows, a sort of mise en scène or stage-setting so to say.

We now concentrate on a rather macabre type of imagery that

we intended from the very beginning of our paper to be the center point of this

posting. This deals with decapitation or beheading, and focusses on

one photograph in particular that is often used in portrayals of the Turkish

genocides against the Christian subjects of the Empire.

Our approach will be to show in this coming final section or main body of the paper that there has been an evolution of the use of a particular photograph of decapitated ‘heads on a platter.’ This gruesome genre of photograph initially had the sole purpose of suppressing any mutinous instincts whatever of dissident non-Muslim populations in Ottoman-held domains.

We believe that the next quite clear step in the evolution of how the photographs should be perceived is that they were trophy photos displayed and even distributed for sale at a very small fee to the masses to instill terror.

The photograph ultimately morphed into being a sort of trademark or emblem of a system of sustained violence. Such photos characterized the routine, graphic violence and horrific behavior of the oppressor. The viewer inevitably ends up asking “How barbaric can one get in maintaining Turkish dominance?”

DECAPITATIONS

One can easily document the view that there seems to be a long-standing, morbid fascination with grisly, macabre images and gruesome photographs, especially those that feature beheadings or decapitations - not just of Armenian heads but virtually any head. We frequently laugh mockingly when we see or hear warnings on the TV that what follows may not be suitable for viewing, or that it graphically represents violence and death. Then, talking back to the TV, we ask, “Why show it?” They know full well why – it caters, actually ‘sells,’ to a gore-hungry audience. For us, it amounts to the lady protests too much.

There is a massive amount of very old historical evidence, along with supporting imagery, showing that it was a long-established practice among warlords, as their armies moved from the far east of Asia westwards to pile up the skulls of conquered enemies. (Recall the Vasily Vereschagin painting “Apotheosis of War”.) Such traditional behavior created a climate of terror, reflected barbarism and foreshadowed doom. Skulls of one’s enemies were a symbol of victory. It reflected a will and ability to sow death and devastation.

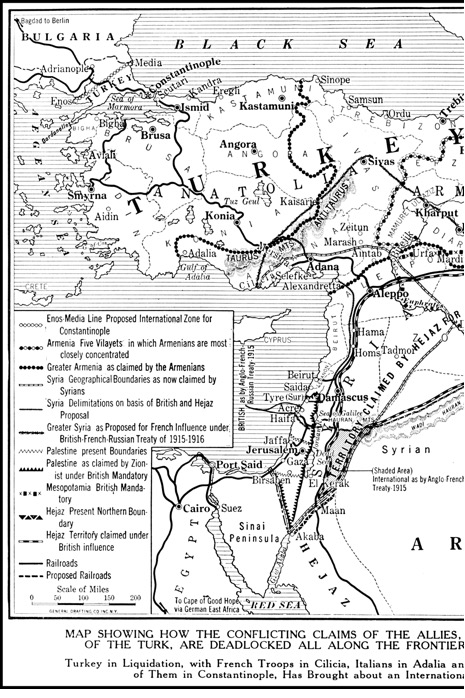

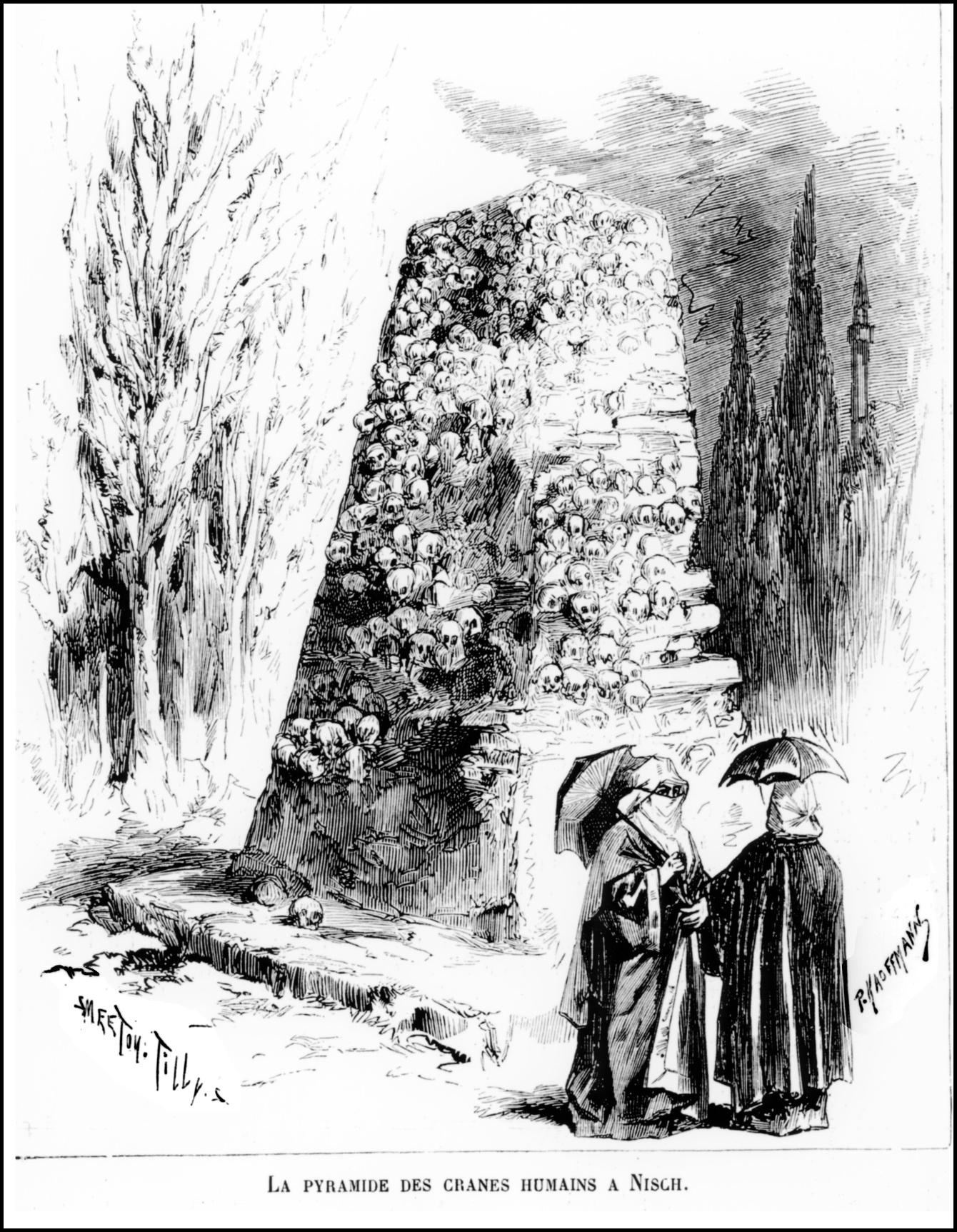

Perhaps the best of known real orderly arranged pile of skulls today, other than the portrayal of the pile in Vereschagin’s art work, stems from a rebellion in Ottoman Serbia in the Balkans against the Ottoman Turkish Empire in the early 1800s. (Piles of skulls behind glass in Cambodia for the victims of Pol Pot and encased assemblages of skulls of Armenians lost in the Ottoman Genocide and others also come to mind of course.)

The Serbs are described as being badly beaten by a vastly larger army of some 36,000 Turks. But the Serbs did put up a heroic battle at a place called Čegar Hill near a city called Niś in today’s south-eastern Serbia. It is said to be the third largest city in Serbia today.

Ultimately realizing that they were doomed to failure against much superior numbers, the Serb commander apparently shot into a gunpowder keg and ended up blowing up the entire Serb army as well as many of the enemy. Outraged by the decision on the part of the rebels to go down fighting rather than surrendering, the Turkish commander ordered that a lesson be taught to the Serb nation. Following a long-standing barbaric tradition, the Serb bodies were mutilated, and the skin on their heads removed by skillful flaying, stuffed with straw and the heads sent to the authorities in Constantinople, the Ottoman capital. We are told that some 952 of these skulls were initially used to make a skull tower. It was around 15 feet high, and 13 feet wide. The skulls were arranged in 52 rows, with 17 skulls in each row at each side of the tower. Over the years relatives and friends apparently removed skulls for Christian burial and today only 58 skulls remain (Butler, 1993).

Understandably this entire event left a deep wound on the national Serb psyche. However, by 1830 the Serbs had won their independence from the Turks and the tower has long since become a place of commemoration where Serbian bravery and suffering and persistence is revered. (The concept of the Serbs being defenders of their human rights was not then developed but modernists might well justifiably give the entire episode that emphasis or spin today.) We can only speculate that pro-Turks see the Skull Tower as testimony whereby Turkish supremacy was upheld. Again, it does not seem possible in the realm of reality that the Turkish overlords would not realize that having a system of rule that blatantly discriminated against its non-Moslem population and lowered it substantially in the ladder of acceptance and tolerance would necessarily lead to resistance. It was merely a matter of when.

Fig. 2.

Figure 2 above shows an early etching published in L’Illustration 34 année, vol. 78, pg. 53 (22 July 1876). It is of considerable interest since it shows the skull tower at a time when it was fully intact. The French reads in translation Pyramid of Human Skulls at Nisch.

One can easily understand why there is scarcely a place today where one can encounter ‘towers of skulls’ rendered into national monuments for all to see and visit. They harken back to a different time and mentality and reflect a remote reality. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bxJin7gvRpI

The obvious hope is, of course, that this sort of thing does not happen again ‘here’ or anywhere in the civilized world. It is a relic of a savage past. As the old country Armenians used to say, Asdvadz lusseh! [May God hear!].

Whether or not it is a verifiable fact that beheading or decapitation is no longer widespread, some will know that words relating to decapitation and beheading have found way into our vocabulary so unobtrusively that one hardly takes serious notice anymore.

Everyone will have heard the expression “heads will roll” or “he or she will lose his or her head” - meaning dismissal or worse will surely be the consequence of doing something unapproved of by one’s superiors. (Curiously enough, the expression did not originate, as some have suggested with Adolf Hitler, but he apparently liked to use the phrase.)

A PHOTOGRAPH SOMETIMES DESCRIBED

AS THAT OF DECAPITATED ARMENIAN CLERICS

The “Armenian Genocide beheading photograph” that we will focus on is shown in Fig. 3. below.

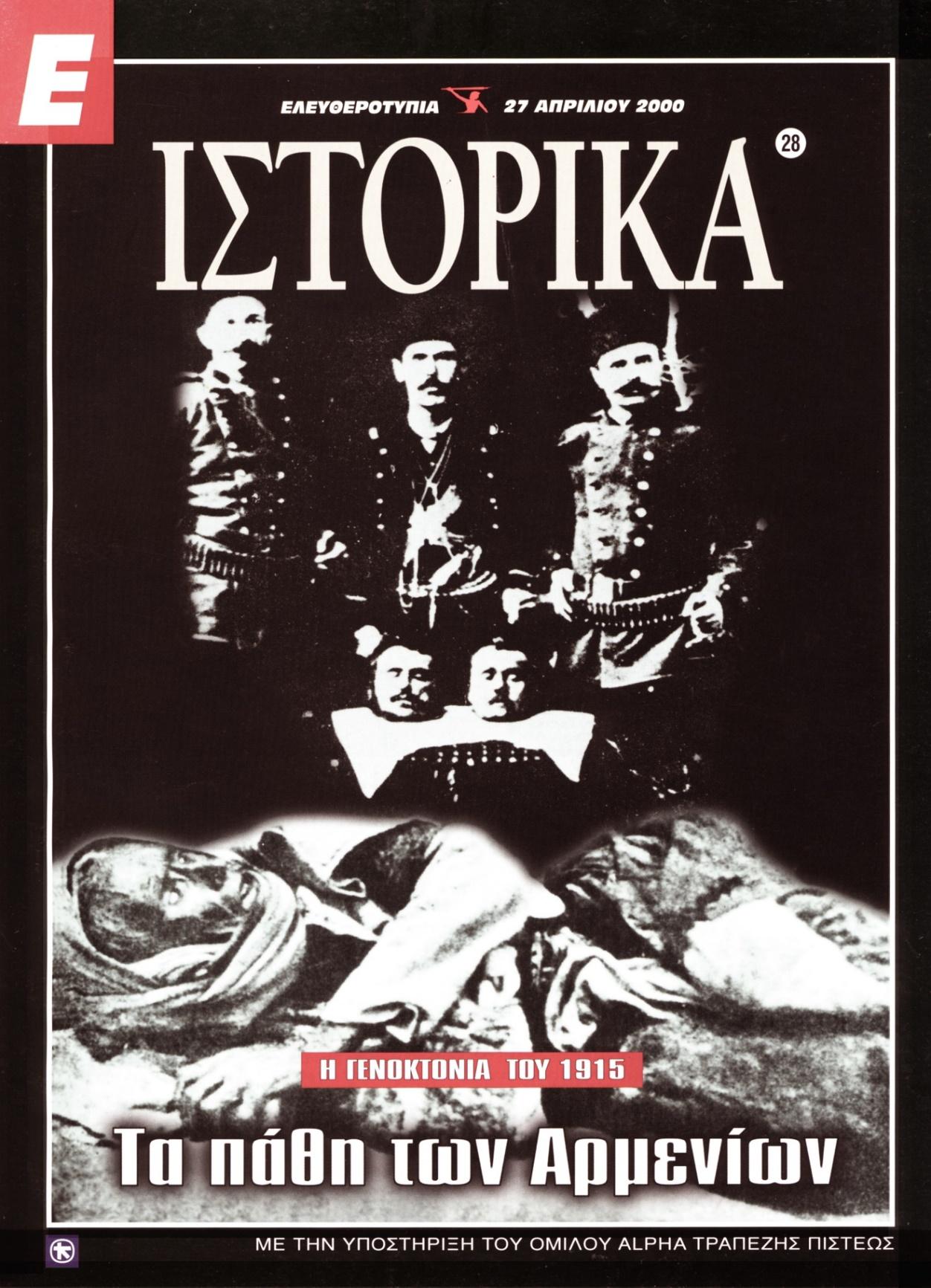

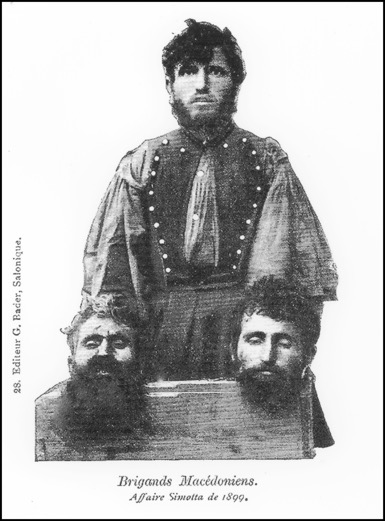

Here the photograph is on the cover of an April 27, 2000 issue of a popular, profusely illustrated Greek history magazine “ΙΣΤΟΡΙΚΑ” published in Athens. This issue features articles on the Armenian Genocide translated from English into Greek. The cover photo shows three Turkish soldiers behind two severed heads positioned on what appears to be an elevated display stand or table. The very same heads and photo appear inside the issue in an article by James Reid. James Reid (1948-2006) was a well-respected historian of the crumbling Ottoman Empire. His dates affirm that he died rather young.

Fig. 3.

Scan of the front cover of Historika, a Greek-language popular history magazine which was issued April 27, 2000. This issue featured a series of articles on the 1915 Genocide of the Armenians in Ottoman Turkey. One thing especially evident is that there is no expression or sign of regret or contrition on the faces of the men in uniform. To the contrary, they are menacing. One might say that they appear “born to the task!” They are certainly, in a phrase, “fighters for the faith” or ghazis.) This fits in well of course with the Turkish narrative that the Armenians, a Fifth Column who favored the enemies of the Empire, were engaged in uprisings against the Turks and were necessarily suppressed harshly.

We tracked down the original source of the imagery reproduced on the upper 4/5ths of this Historika cover, and shown in enlarged format in the text article within. Whether author James Reid or others selected the photograph for his article translated into Greek, we will never know since he passed away in 2006. Asking him would have obviously been the easiest way to establish the origin of the photograph that was used. (He did, incidentally, know modern Greek well.)

On first examination, the image would appear to qualify as an outstanding example of what is often called a “war, or conflict trophy photograph.” Nowadays, taking such photos is sometimes described by professionals with more technical vocabulary as the “capturing of a scene of commemorative violence.” We hasten to say we are not ‘social ‘scientists’ and therefore we are not sure as to what that phraseology means to people in the discipline as professionals – that is those who earn a living at it. But let us for the moment say that it is a fancy way of saying that the perpetrators are proud of what they have done. It would be much like a big game hunter posing with a huge, tusked elephant that he/she has just shot in East Africa.

In this case, perhaps the participants behind the heads on view consider their behavior merely part of “normal police duty or soldiering.” (For a broad coverage of trophy photography see Jakob, 2017).

But that viewpoint of being a trophy photo is only one perspective on the photograph.

We’ll concentrate now on another viewpoint that we shall call Original Intent of the Photographs.

Readers will note that we have put a letter s on the word photograph thus making it absolutely clear that the photo on the cover of the 2000 April issue of Ta Historika is only one example of a number of similar photographs.

Some will be familiar in a general way with the store or number of photographs that exist which one might categorize as “Armenian Genocide Photographs.”

The idea of carrying out an inventory and categorization of Armenian Genocide Photographs has long been extant. Fair to say for history’s sake, we discussed the problems many years ago with Missak Kelechian, now in California - then in Beirut), and the now-late Karekin Dickran (of Denmark but also originally from Beirut). We corresponded for some time about not only the need, but the implementation of a plan for producing something really useful.

We (ADK and ELT) have believed for some time that the field was not yet ready to put things into a proper data bank/base or registry. Far too little precise information was available that could be drawn upon to produce such an admittedly much-needed resource. The idea essentially died, or at least was put on the ‘back burner.’

In retrospect, we believe that we took the right pathway about people such as ourselves who were doing scattered studies on “Armenian Genocide Photographs.” Work was needed before rigorous attempts were made to categorize and pigeon-hole them. In a word, one needs sturdy building blocks before trying to construct something durable!

Moreover, issues of copyright, permissions, psychological or administrative territoriality, problems of unwillingness to share etc. were at the time circumvented by using another, perhaps unconventional approach.

Dr. Tessa Hofmann, having probably learned the hard way by dint of the Vereschagin painting/photo debacle, realized that one must examine and evaluate photographs intended for current-day use as thoroughly as possible, and apparently decided to make a serious start at properly categorizing, identifying and storing images for use by scholars. A pioneer paper was published in the early nineties (Hofmann and Koutcharian, 1992).

What we learned from studying that paper was enough to convince us that there was a great deal of work needed to fill in the blanks. To be very blunt, very little had actually been done about identifying Armenian Genocide photographs rigorously – or at least very little that we knew about. Everywhere we turned we encountered ‘used’ and ‘re-used’ photos that were at best simply carelessly described from the outset. It clearly had not been a priority.

Asbed Bedrossian was good enough to set up a Rubric for us on Groong, the Armenian News Network, which we use as a vehicle for “publishing” our carefully gained knowledge from time to time. The rubric was named “Witnesses' to Massacres and Genocide and their Aftermath: Probing the Photographic Record.”

https://www.groong.org/orig/Probing-the-Photographic-Record.html

It is not our intent here to provide anything more than a brief coverage of those real ‘decapitation’ photos very reminiscent of the photograph on the cover of Ta Historika. There are a number of them but so far as we are aware they virtually all derive from the Macedonian revolt period in the very early 1900s.

But as a broad beginning statement, we should point out that there were a number of photos that some have identified as of the Armenian Genocide genre printed on Postcard stock that found their way considerably later into circulation. Even today the Turkish paper ephemera market occasionally offers them for sale. It has been virtually impossible for us to date these precisely but one can guess that they were printed and distributed soon after the war ended and efforts were afoot to work on Peace and Reconciliation. It became a priority.

These photos on Postcard stock, were utilized we believe to emphasize the barbaric and inhuman behavior on the part of Turks against Armenians during the Genocide and various persecutions. We emphasize, they are all relatively poorly printed on Postcard Stock. The photos include bodies of those murdered, a range of public hangings, excavated sites with skulls and bones and the like.

Some of these photographs were even encountered by American relief workers - starting in 1919. For example, relief worker Mary Hubbard of the famed missionary family ‘The Hubbards of Sivas’, was sent to Sivas as part of the Leviathan relief group (see Groong Witnesses to Massacre “Ninety-six years ago today. The S.S. Leviathan leaves Hoboken, New Jersey on Sunday, February 16th1919 with nearly 250 early responder volunteers of the American Committee for Relief in the Near East anxious and determined to help in ‘reconstruction.’ Talented and willing American help for survivors of the Turkish Genocide against the Armenians is on its way. A detailed list of workers and their efforts to salvage remnants, and “put the fragments together.” By Abraham D. Krikorian and Eugene L. Taylor. February 16, 2015. https://www.groong.com/orig/ak-20150216.html.

Mary’s private papers included a number of such photographs. See Palmer, Dutton Hubbard, Araxi (1997) editor, Triumph from Tragedy. Privately Printed, 152 pages. Also, see our video entitled The amazing story of an Armenian Orphan, Araxi Hubbard, by Abraham D. Krikorian and Eugene L. Taylor, February 6, 2014 at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=D7sL1Wl7qJ0

Araxi donated these photographs to Project Save when she feared that having to undergo a serious hip operation might interfere with her life. When we visited her in 2003, she gave us permission to make copies for our use. Happily, Araxi lived many years after that unwarranted panic.

As mentioned, details are not known about exactly how or when these ‘Armenian Genocide’ photos usually printed on Postcard stock were made available generally but we can say that there are even today examples of these sold usually by Istanbul dealers, and are considerably overpriced and very poorly described. What we mean by “poorly” really means that labels or captions are inevitably guessed at. Frequently, a long-standing error has been merely copied and pawned off as authoritatively described.

We ourselves shall virtually ‘dismiss’ exactly how or under which aegis these are described because when we have attempted to get more detail on them, very unsatisfactory responses have inevitably been given. As mentioned already, nothing should be “obvious” when trying to carry out investigations.

The late Dr. Sybil Milton, an expert on the Nazi Holocaust against the Jews, and Gypsies etc., and photography as witness to genocide, even spent time and analyzed the photographic materials of Armin Wegner on the Armenian Genocide in an exceeding detailed and scholarly context. We think her 1989 paper is a masterpiece (Milton, 1989). She deals with many critical aspects of Armin Wegner’s photos. Because there were so few photos relatively speaking, Wegner’s photos have assumed a place of greater importance than they might have been, using today’s more rigorous standards.

DISCUSSION OF POSTCARD PRINTS

LIKE THOSE OF THE DECAPITATED ARMENIANS

As already related, we have seen old Postcard stock photos of the decapitated heads scenario for sale on various occasions – most often on eBay where one sold for $150 not that long ago. The quality was not good. Not only had they aged, they were not good to begin with. A photograph or two owned by friends are in a bit better condition than the ones we show below but unfortunately none bears a legible postmark that might help in dating them. Printing photos on Postcard stock was a common practice, especially in the period of the First World War and immediately thereafter and we ourselves have never encountered any photographic print of this genre other than on Postcard stock.

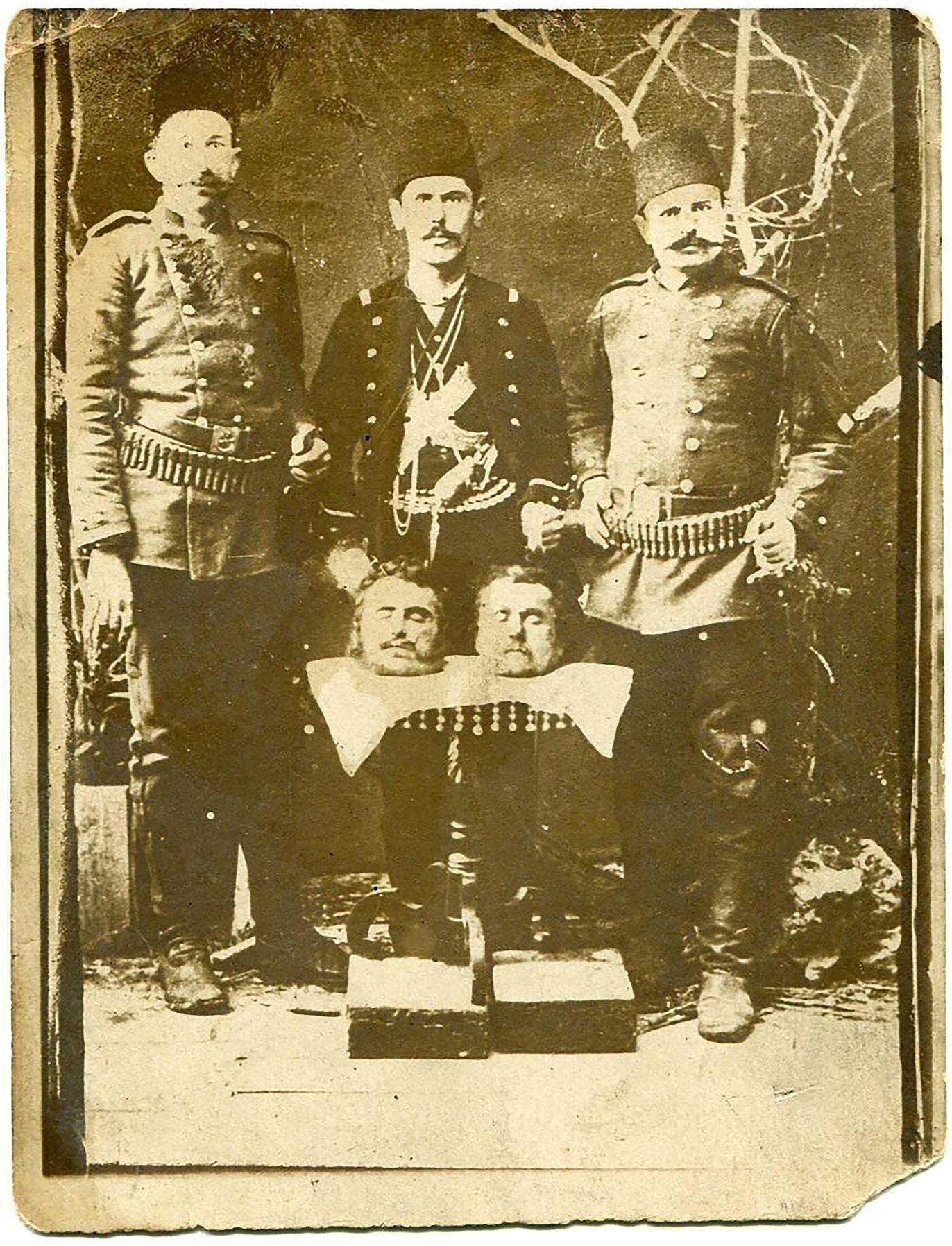

Figs. 4a and 4b below are scans of photographs printed on Postcard stock showing the two heads that are the same as those that appear on the 1980 cover of the Greek magazine Historika. One can see the aging that has taken place.

Fig. 4a.

Fig. 4b.

Needless to say, no one, either victim or perpetrator is specifically identified in what we have seen.

In a publication issued in the USA in 1920 entitled Martyred Armenia and The Story of My Life

by Krikor Gayjikian there is a photograph included on

pg. 99 with five heads captioned ‘The

Turks according to their Mohammedan faith, and their cultivated blood thirst,

are proud of the Armenian heads.”

https://books.google.com/books/about/Martyred_Armenia_and_the_Story_of_My_Lif.html?id=MMElAQAAMAAJ

While the photo in Gayjikian shows 5 severed heads, the photo of interest to us especially, has two heads. Otherwise they are quite similar.

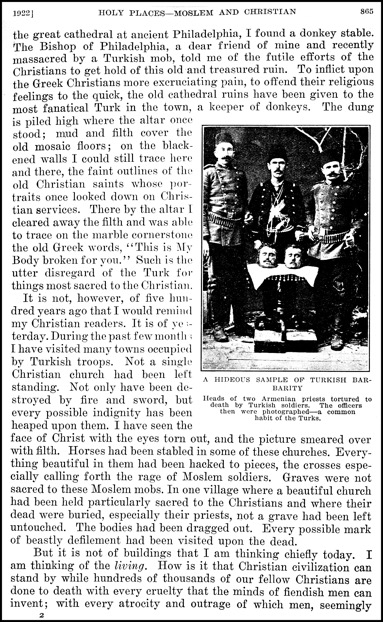

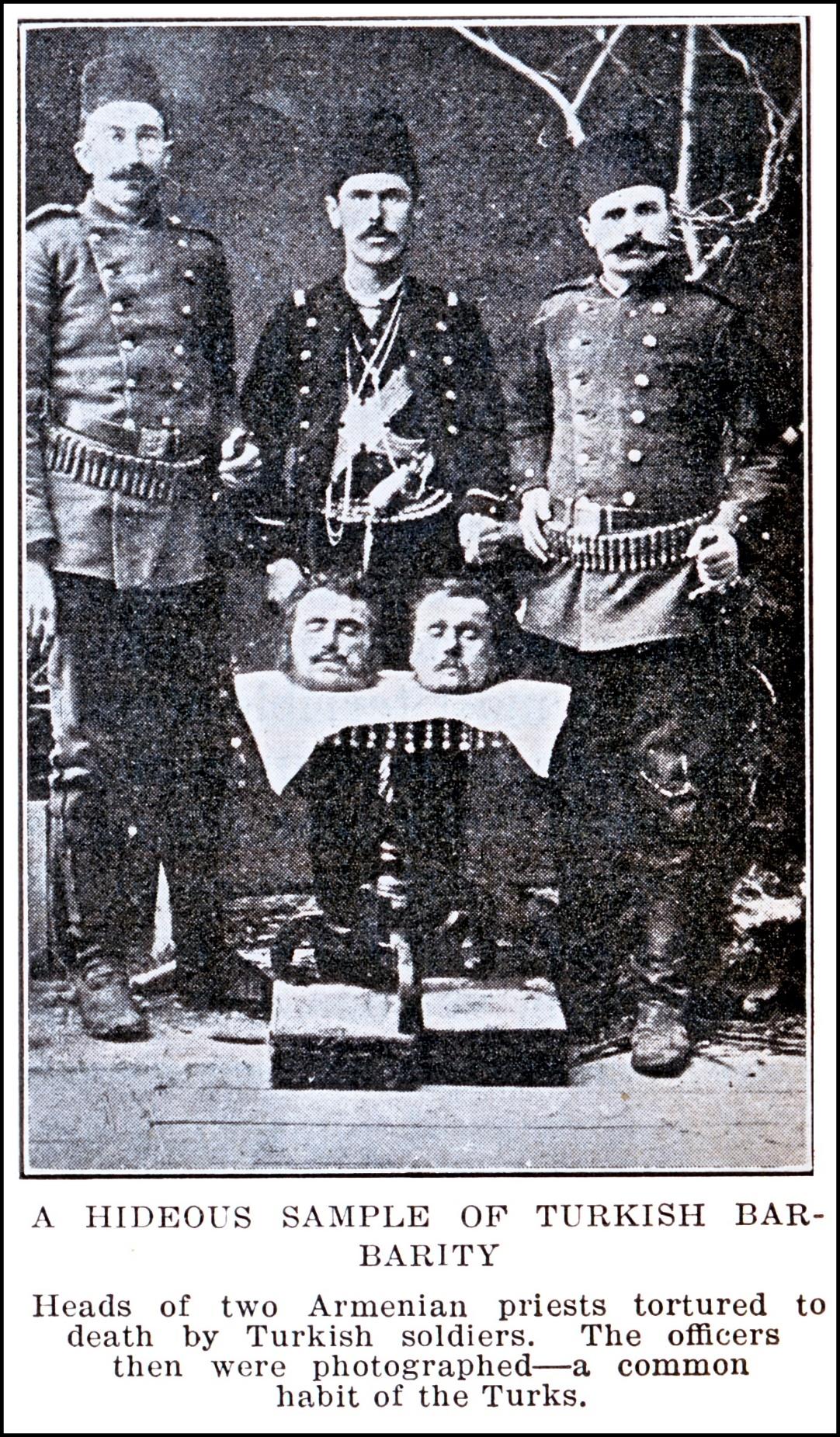

The first place ever where we recall having encountered a published photo of the actual photograph, captioned at that, of the exact heads shown on the Historika cover and the Postcard prints was in The Missionary Review of the World, November 1922. It is in an article by Reverend S. Ralph Harlow, Professor of Sociology at the International College in Smyrna. (Harlow, 1922). On page 865 we see a photograph entitled “Hideous example of Turkish Barbarity.”

Fig. 5a.

Page from The Missionary Review World volume 65, no. 11 November 1922.

An enlargement of the photograph is included as Fig. 5b.

Fig. 5b.

“Heads of two Armenian priests tortured to death by Turkish soldiers.

The officers then were photographed ̶ a common habit of the Turks.”

As already mentioned, the victims remain unidentified although in our opinion the heads bear some remote resemblance to those clerics whom they were professed to be some time back. (We will not bother giving many details here since they were wrong and would serve only to confuse matters but we would probably be remiss not to point out that a 31 page booklet by one Krikor M. Zahigian published in 1923 in America, includes an exact photograph of the two heads on pg. 12. It has the caption. “Heads of Martyred Armenian Bishops and their Executioners.” No mention is made of the origin of the photos or the caption. One difficulty is that the Zahigian publication is rather rare and seldom encountered (see Zahigian,1923).

We put all this apparent failure to get things right into the category of errors made long ago and at a time when such things were not deemed as critical as we might want today in terms of modern scholarship - especially the kind of scholarship that focuses on rigorously attesting and attributing photographs relating to the late Ottoman Genocides. Besides, more modern day users would often fall back on the viewpoint that it all fits into a well-known and attested pattern.

Our recent postings on Groong cited above show that we have a great deal of evidence that photographs, like statistics, can be adjusted. Some have even said that they can be twisted to suit various agendas. The main point we believe is to be candid about it – that is to say, be as direct as the situation merits about what is known and what is not.

WHAT IS THE PHOTO OF THE HEADS REALLY ABOUT?

The photo of the heads in question actually shows heads of Macedonian dissidents slain by Turks in 1903.

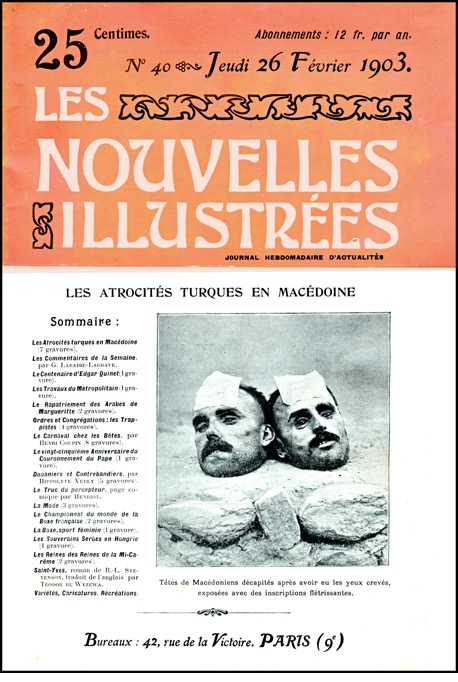

The exact Decapitation photo appears in a rather rare issue of a French journal. We own a copy of the issue with a cover as shown in Fig. 6. We also own a bound copy of the journal that contains the issue but without the cover to the specific issue. Some readers will know that it was not uncommon for libraries and others to bind journal issues together for a durable volume but devoid of their covers.

Fig. 6.

Cover of Turkish Atrocities in Macedoine.(26 February 1903). From our collection.

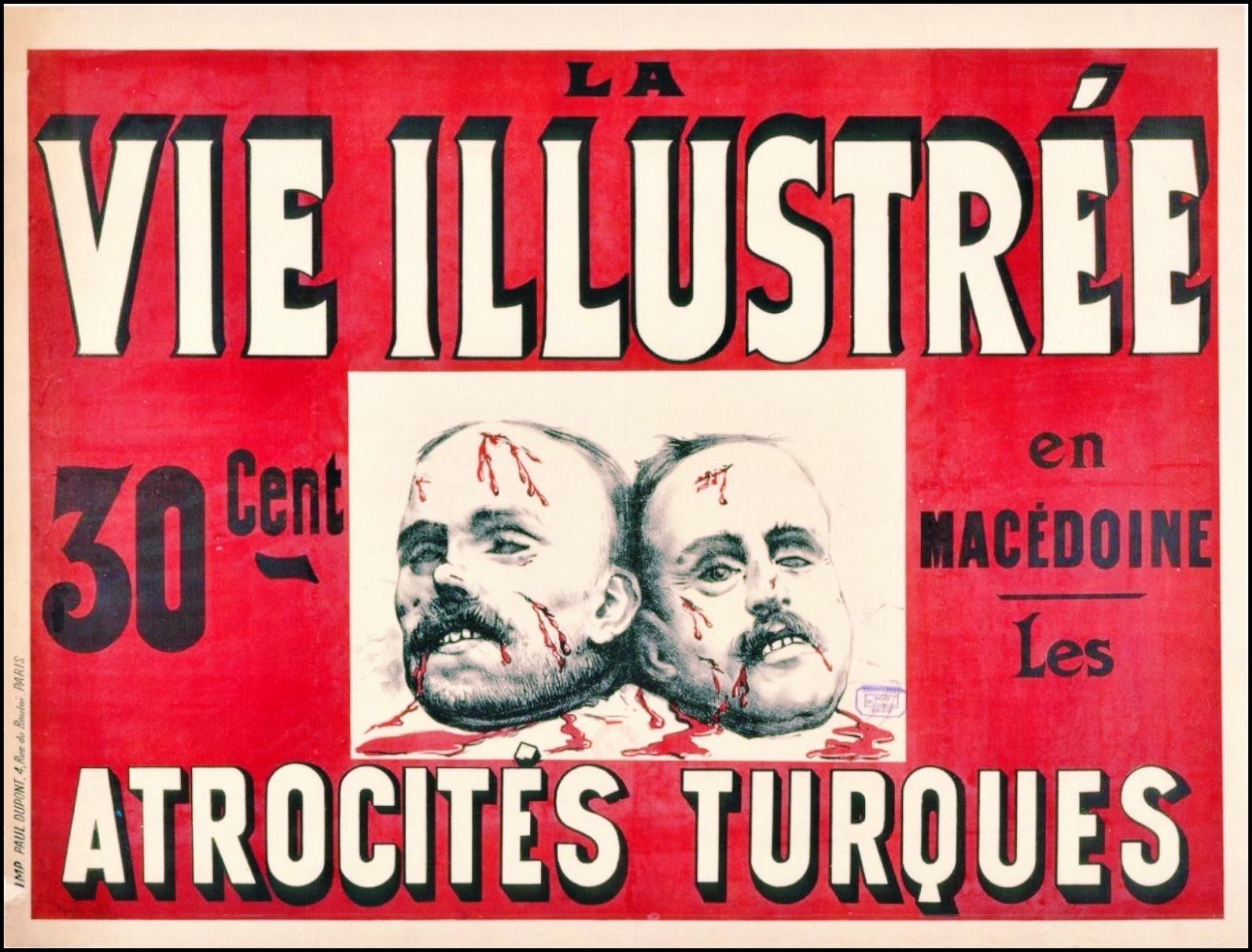

Figure 7. below shows that the well-known

Poster Printer Paul Dupont, 4 rue Bouloi, Paris was

apparently engaged to produce a colorful “Affiche” or placard advertising the

issue shown above in Fig. 6. The price for the single issue had increased from

25 to 30 centimes.

Fig. 7.

Placard on Turk Atrocities. A comparison of the image with

that on front page of the 26 February 1903 issue (Fig. 6.) shows that it is

exact. except for the red and blood instead of paper patches.

At this point one might cynically quip that “A head is a head!” Equally repugnantly, “Once you’ve seen a head from a person who has been decapitated, you’ve seen them all!’ Had the severed heads been described ‘generically’ when they were included in the considerably later publications, one would have avoided one major aspect of the problem. The problem or difficulty is generated by claiming a supposedly precise victim when it was, as we now know, incorrectly identified. It had better be correct. Otherwise your critics will seize the opportunity to try to discredit it all. This is itself madness since the practice of beheading was widespread among Turks. One simply might ask those who complain “Did Turks routinely decapitate or not?” There is too much evidence to show that they did. It would be futile to deny it.

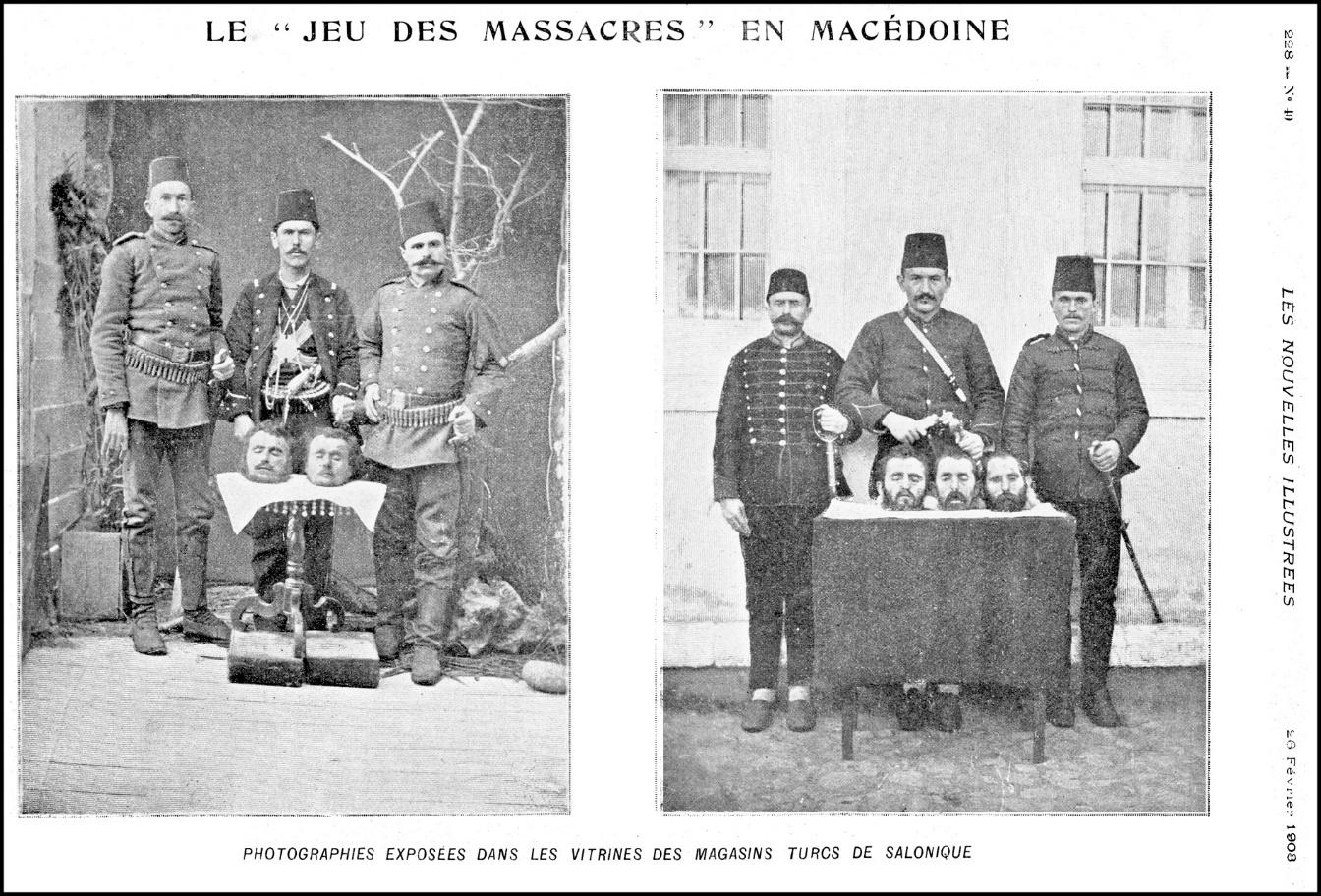

The caption of the exact photograph in the French journal where it was first published says in translation, “Massacre Games” in Macedonia (Le “jeu” des massacres en Macédoine). Additional commentary in the text relates that this photograph and similar ones were displayed in windows of Turkish shops in cities like Salonica and Monastir (see Fig. 8. below.)

Fig. 8.

From an issue, now quite

rare, of Les Nouvelles Illustrées.

Journal hebdomaire

d’actualités (Paris) (No.

40, 1903).

We will forego offering any details here on the savage suppression of insurgent Macedonians by Turkish troops in Macedonia in 1903. Recall that Sultan Abdul Hamid II was then on the Ottoman throne but it may be of interest to read below what a magazine entitled Christian Work and Evangelist (New York) vol. 74 no. 1884 March 28, 1903 pg. 444 had to say about the matter of beheadings.

“There is a fearful picture which L’Illustration of Paris [specifically the cover of L’Illustration 61é année, 21 Février 1903 and accompanying article by Albert Malet on pg. 134] prints of atrocities committed by Turkish soldiers in Macedonia. In the picture we have presented, behind an upright cabinet six soldiers standing at attention, muskets in hand, while on the cabinet in front in a row are the three heads of Macedonians cut off from their bodies ̶ the faces being very easily recognizable to those knowing them. The French papers now arriving [in New York] are filled with written accounts and ghastly photographs of Turkish atrocities in Macedonia, among which is a child whose knee had been cut open by a sabre in the hands of an Albanian, for no other cause than the very pleasure of the thing. Good observers ̶ among others a consul of one of the great powers ̶ state positively that they know of 200 assassinations committed in the Uskub region, a territory about the size of one of the departments of France, and it is believed that this is only about one-fifth of the actual occurrences. The photographs are significant and inclusive, because they show that the work is not the result of madness on the part of the soldiers, but that it is pre-meditated and calculated, as they have allowed themselves in groups around the heads of their victims. It is to be further noted that it was immediately after the carnage that these photographs were taken, but in the place of business of a professional photographer, to which place the heads were carried in the sacks, and taken to the Turkish authorities, who had received the formal order to “show themselves” pitiless. Needless to say the command has been obeyed!”

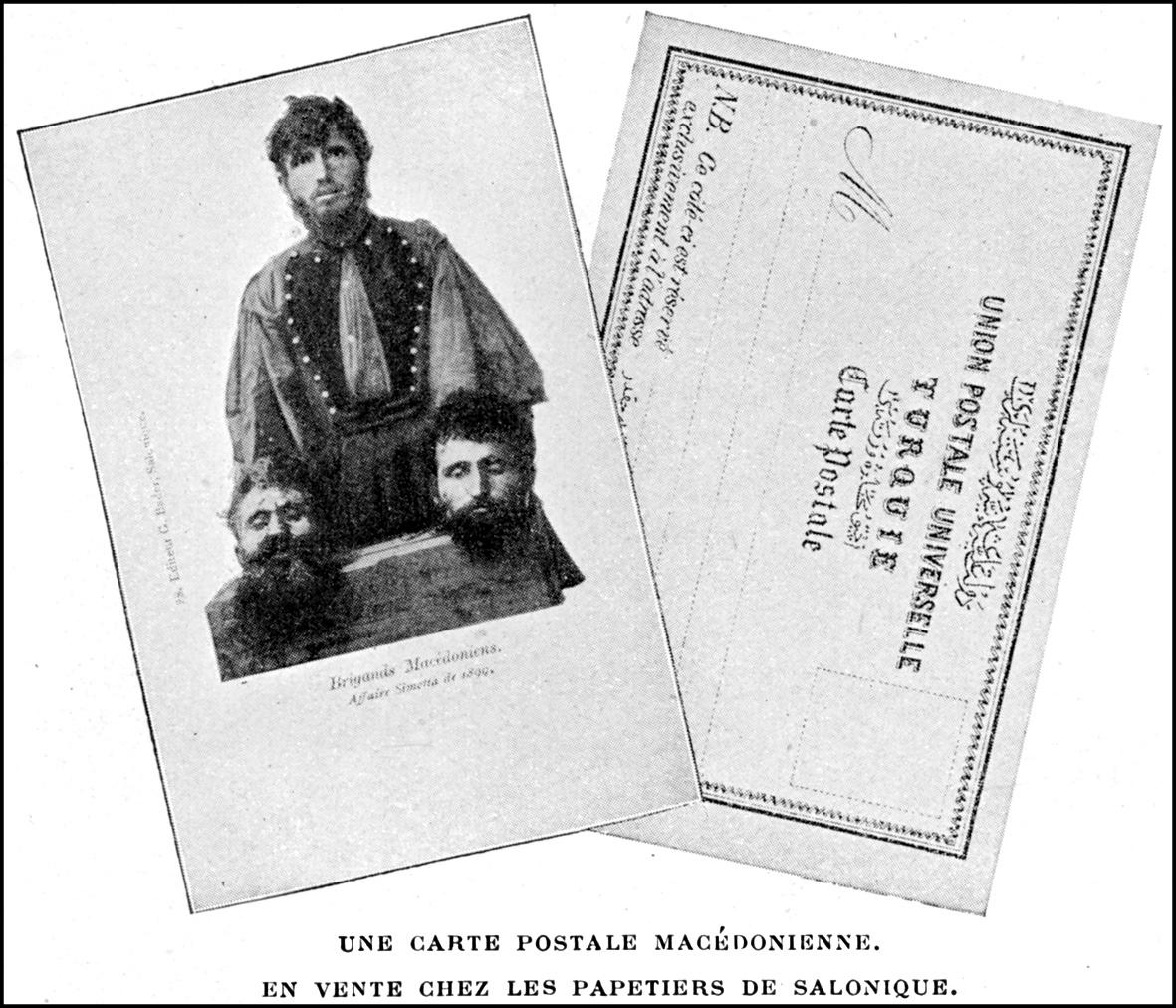

In the 9 January 1904 issue of Le Tour du Monde there is an article by writer Albert Malet entitled “En Macédoine – Au vilayet de Monastir” which includes a photograph of a fellow with two decapitated heads displayed before him and an accompanying explanation that it comprised a postcard which was on sale by Salonika stationers.

What is especially interesting about this particular photograph, probably the oldest of the genre date-wise and which differs from the one that has especially interested us because of the supposed identity of the victims being Armenian clergymen, is that it shows how marketing of such photographs was done. The print on Postcard stock had a prominent “back” that displayed the place where the name and address of the addressee could be written in etc. It was therefore a ‘real’ postcard - not like the many later replicas that were not really well done, or did not show clear-cut places where the name and address of the addressee was to be written in. There are so far as we know, not many of those which were so ‘elegantly’ produced, available for sale (see Fig.9).

Fig. 9.

A Macedonian postcard for sale in Salonika stationers. Scanned from page 20 of our copy of “En Macédoine. – Au vilayet de Monastir” by Albert Malet in Le Tour du Monde X, N.S. 2e LIV, no.2, pgs. 13-24 (1904, Janvier 9).

An enlargement of the image on the front of the card is included below (Fig. 10.).

Fig. 10.

Close-up.

In a relatively recent book published to accompany an exhibition entitled “Camera Ottomana: photography and modernity in the Ottoman Empire, 1840-1914,” at Koç University Research Center for Anatolian Civilizations, Istanbul, April 24 – August 9, 2015, we find a number of images that are of some interest because they deal with the beheading photos. Note that we say “some” interest.

Overall, it is not a very informative volume and leaves much to be desired especially considering its price. It certainly is no place where one will learn anything in detail about the photographers who were the most active in the Empire – namely the Armenians and Greeks. The vast majority had not abandoned Christianity.

Note that the date chosen for the opening of the exhibit did not escape our attention. April 24 is the special date that marks the onset of the genocide against the Ottoman Armenians in 1915 and is commemorated worldwide by Armenians.

In that exhibition catalogue, which we purchased only very recently largely out of curiosity, we encountered a fairly extensive treatment of the photographs published in the French Press that featured beheadings displayed for public viewing (see pgs. 120 ff.) None of the photos shown derived from anything other than the print media. (Since we believe we own all of the French press publications featuring the beheadings on display in Macedoine in that period, or at least much of it, we had hoped that one might possibly be included that reflected original presentation(s) for sale like the one shown in Fig.9. We were disappointed.

We will not go into much detail here except to say that the Macedonian rebels and Bulgarians (and even the Armenians) indeed each ethnic group in its and by way of its own special means and effort, did what they felt they had to do. They hoped to attract foreign attention - especially political and even financial support from those sympathetic to their cry for help and relief from Turkish oppression.

The extent of the Turkish atrocities against the Christians that the dissidents worked so hard to draw attention to and publicize never let up. They simply got worse and the suppression increased and became ever more ugly. (Parenthetically, it worked a bit for the Macedonians but not at all for the Armenians who did not constitute a majority even in historic eastern Anatolia/Armenia.) Human rights, as we even marginally appreciate them today, were criminalized in Ottoman lands.

Administration by massacre aptly describes how the Turks ruled. Shockingly enough, today one hears the bewildering and offensive description of keeping the Palestinians in line and suppressing them by regularly ‘mowing the grass.’ A sad and obscene but admittedly effective description.

American missionaries were even kidnapped and held for ransom to muster support on behalf of the dissidents (cf. e.g. Woods, 1981;Wolons, 2003).

By now we hope we have given a good overview of those kinds of atrocity photographs involving beheaded men. They have today become quite generic in their use. Comprehending what they mean and typify has very little to do with their history.

The human head has so much symbolic value that seeing one severed from the torso sends chills up most spines. Nothing more need be said on that account.

In closing we will say that there are many advantages to using a real photo or photos of decapitations. They do bring things home and render the true reality of what occurred more vividly. This is especially so when the photographs are close-ups and there is little doubt about what one is viewing. The difficulty is that there is no large store of images relating the various atrocities from which to select.

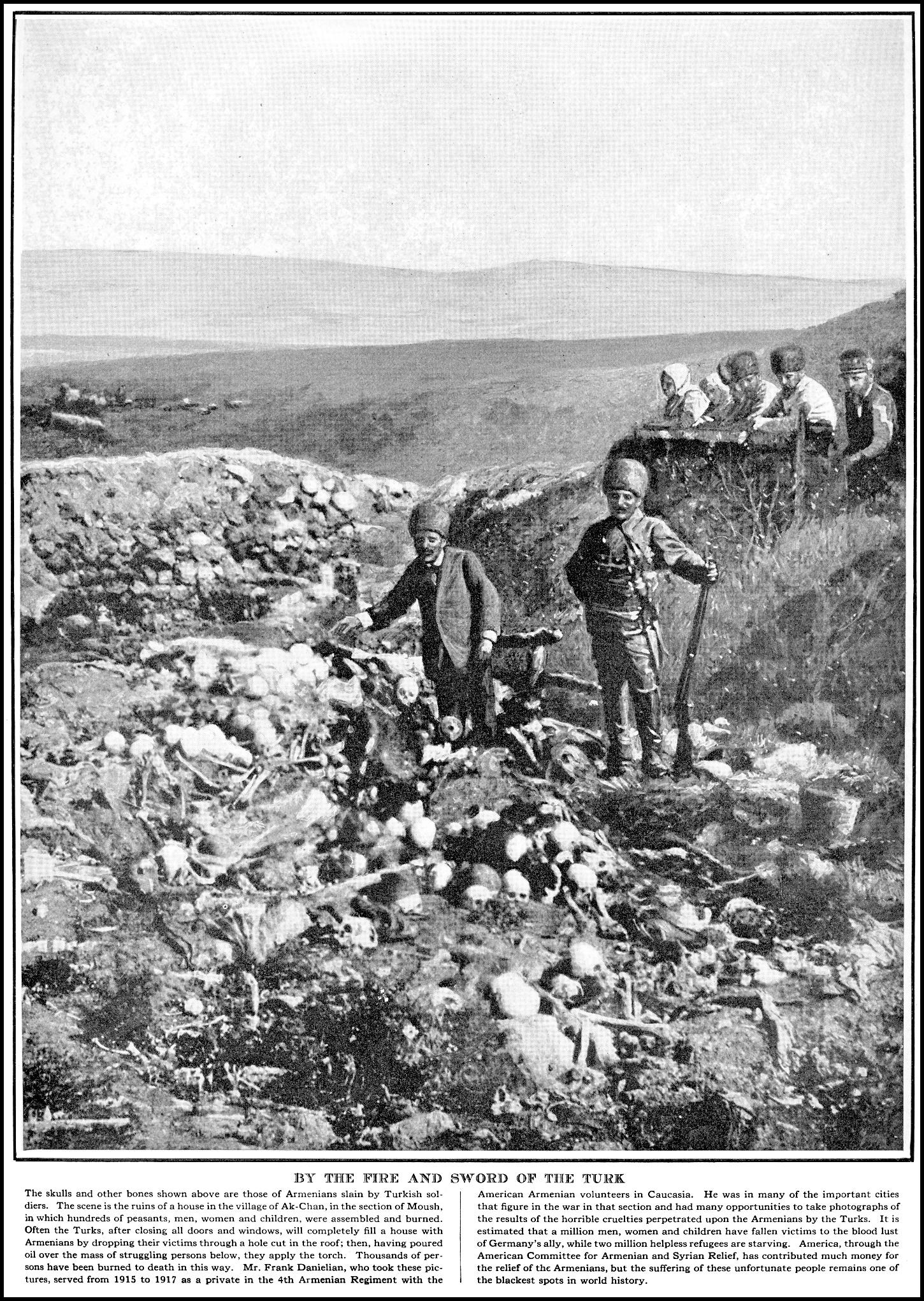

Figure 10 below shows there are a few photographs of distant views of skulls that were recovered from sites of massacres that had been carried out. Even though they are not close up, they certainly get the point across.

Perhaps the advantage, if one may pervert the word, of using the available photographs showing the perpetrators posing behind the skulls, is that they convey the savagery and impunity of carrying out such inhuman acts. The sheer number of skulls in the other photos, while very real and distressing, are skulls that are advanced in their decomposition, whereas the heads displayed show the newness of the act and the lack of contrition on the part of the perpetrators. Take your pick.

Fig. 11.

This is a page taken from the June 28, 1917 issue of Leslies’s Illustrated Weekly Newspaper, page 807.

Below is the original caption. Fig. 11. enlarged into 2 sections to facilitate reading.

![]()

![]()

Fig. 12.

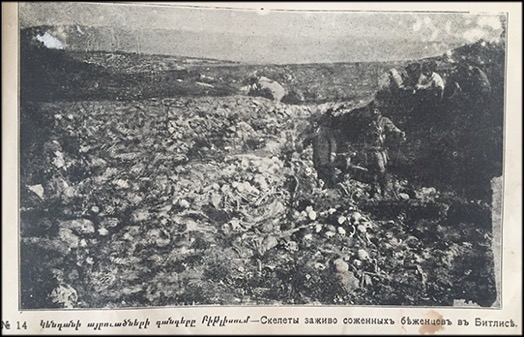

A rather poor quality photograph which was included in a volume published by the Central Armenian Committee, Moscow in 1916/1917. The captions of all the photos are in Armenian and Russian. A quick examination will show that there is a broader field included in the photograph shown in Leslie’s (Fig 11). The captions are complementary and support each other. We learn in one that the scene is a village in Moush, the Armenian volume points out additionally that it is the Kaza of Moush in Bitlis Vilayet.

Fig. 13.

Yet another photograph from our files showing skulls and some bones.

Photograph of Armenian skulls. A rather morbid scenario. (From authors’ collection.)

REFERENCES

(Citations in text can be found alphabetically below)

Bloxham, Donald(2005) The Great Game of Genocide: Imperialism, Nationalism, and the Destruction of the Ottoman Armenians. (New York: Oxford University Press).

Bloxham, Donald (2009) The Great Game of Genocide: Imperialism, Nationalism, and the Destruction of the Ottoman Armenians. (New York: Oxford University Press.)

Butler, Thomas (1993) Yugoslavia Mon Amour. The Wilson Quarterly vol. 17, no.1 118-125.

Çelik, Zeynep, Edhem Eldem, Hande Eagle (2015) Camera Ottoman: photography and modernity in the Ottoman Empire, 1840-1914. (Istanbul: Koç University Press.)

Fleming, Jackson (1919) Mandates for Turkish Territories. Asia. The American Magazine of the Orient Vol. 19, no. 12 pgs. 1195-1202.

Gayjikian, Krikor (1920) Martyred

Armenia and the Story of My Life. (Cincinnati: God’s Revivalist), 308

pages.

El-Ghusein, Fa’iz (1917) Martyred Armenia Madhābiẖ fi Arminiyā. English. (London: C.A. Pearson, Ltd.) 56 pages.

El-Ghusein, Fa’iz (1918) Martyred Armenia. New York: George H. Doran Company, 52 pages. (Original Arabic translated into English). Completed by the author at Bombay 3rd September 1916.

Harlow, Rev. S. Ralph (1922) Holy Places – Moslem and Christian.. Moslem demands and the responsibility for disturbances in the Near East Missionary Review of the World vol 65, no. 11 (November), 863-866.

Hofmann, Tessa and Gerayer Koutcharian (1992) Images that Horrify and Indict”: Pictorial Documents on the Persecution and Extermination of the Armenians from 1877 to 1922.” The Armenian Review vol. 45, No. 1-2, 53- 184.

Jacob, Joey Brook (2017) Beyond Abu Ghraib: War trophy photography and commemorative violence. Media, War & Conflict vol. 10, no. 1, 87-104.

Krikorian, Abraham D. and Eugene L. Taylor (2011) “Achieving ever-greater precision in attestation and attribution of genocide photographs”, pgs. 389 – 434, in The Genocide of the Ottoman Greeks: studies on the state-sponsored campaign of extermination of the Christians of Asia Minor, 1912-1922 and its aftermath:history, law, memory. Edited by Tessa Hofmann, Mathias Bjørnlund, Vasileios Meichanatsidis (New York: Aristide D. Caratzas).

Laycock, Jo and Francesca Piana

(2020) Aid to Armenia: humanitarianism and intervention from the 1890s to the

present. (Manchester: Manchester University Press.).

Milton, Sybil (1989) Armin T. Wegner: Polemicist for Armenian and Jewish Human Rights. The Armenian Review vol. 42, no. 4, 17-40.

Sekula, Alan (2016) Photography Against the Grain.: essays and

photo works, 1973-1983. 2nd edition (1st edition was

1984). London: MACK.

Wolons, Roberta (2003) Travelling for God and Adventure: Women missionaries in the late 19th century. Asian Journal of Social Science vol. 31, no. 1, pgs. 55-71, esp. at pg. 61 ff.

Woods, Randall B. (1981) The Miss Stone Affair. American Heritage Vol. 32 no. 6, 26-29.

Zahigian, Krikor M. (1923) One

Page of Armenia’s Tragedy: a story of the years wherein we have seen evil; the

testimony of an eye witness. With a Foreword by

Henry Turner Bailey. Pacific Palisades, California: self-published. 31 pages.

FOLLOWED BY ENDNOTES

[1] For example, an entry starting with the heading “Photographs of Armenians lying in the road,

dressed in Turbans, for dispatch to Constantinople.” “The Turkish Government

thought that European nations might get to hear of the destruction of the

Armenians and publish the news abroad so as to incite

prejudice against the Turks. So after the gendarmes

had killed a number of Armenian men, they put on them turbans and brought

Kurdish women to weep and lament over them, saying that the Armenians had

killed their men. They also brought a photographer to photograph the bodies and

the weeping women, so that at a future time they might be able to convince

Europe that it was the Armenians who had attacked the Kurds, that the Kurdish

tribes had risen against them in revenge, and that the Turkish Government had

no part in the matter. But the secret of these proceedings was not hidden from

men of intelligence, and after this had been done, the truth became known and

was abroad in Diarbekir.” From pg. 45 of al-Ghusein’s “Martyred

Armenia”, 1917; pg. 38 of al-Ghusein’s “Martyred

Armenia,” 1918.

© Copyright 2021 Armenian News

Network/Groong and the authors. All Rights Reserved.

| Home | Administrative | Introduction | Armenian News | Podcasts | Feedback |