Armenian News Network /

Groong

THE POWER OF A

PHOTOGRAPH AND ITS RECYCLING OVER TIME

Armenian News Network / Groong

April 23, 2021

Special to Groong by Abraham D. Krikorian and Eugene L.

Taylor

Long Island, NY

In addition to misidentification or

incorrect attestation of images, one is confronted on occasion with relevant

images that have been, or are still being used without

specific qualification as to when they were originally used, or where or by

whom they originated. Whether this has an effect on suitableness for their use

in a specific, more modern-day presentation the user will have to decide.

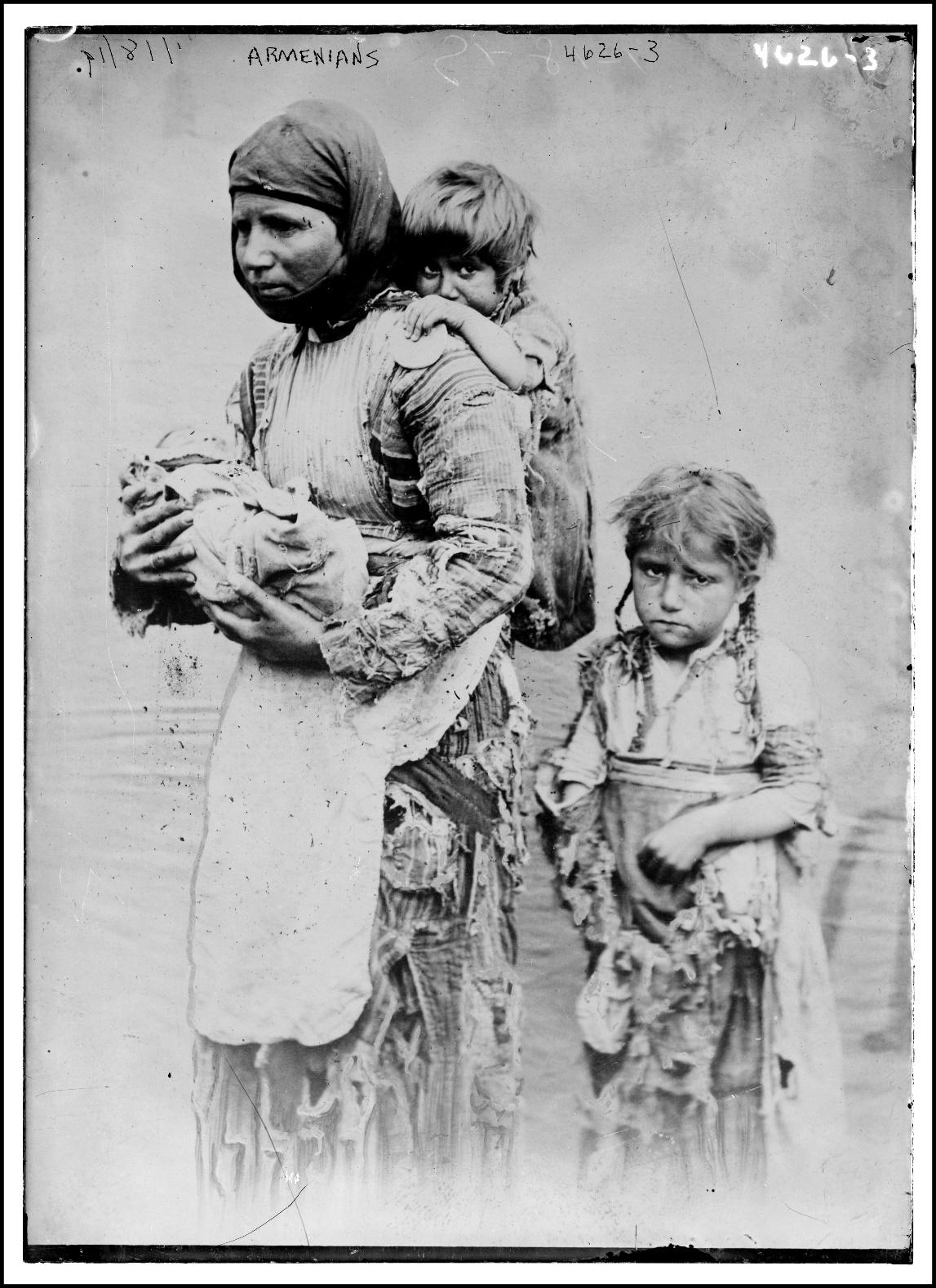

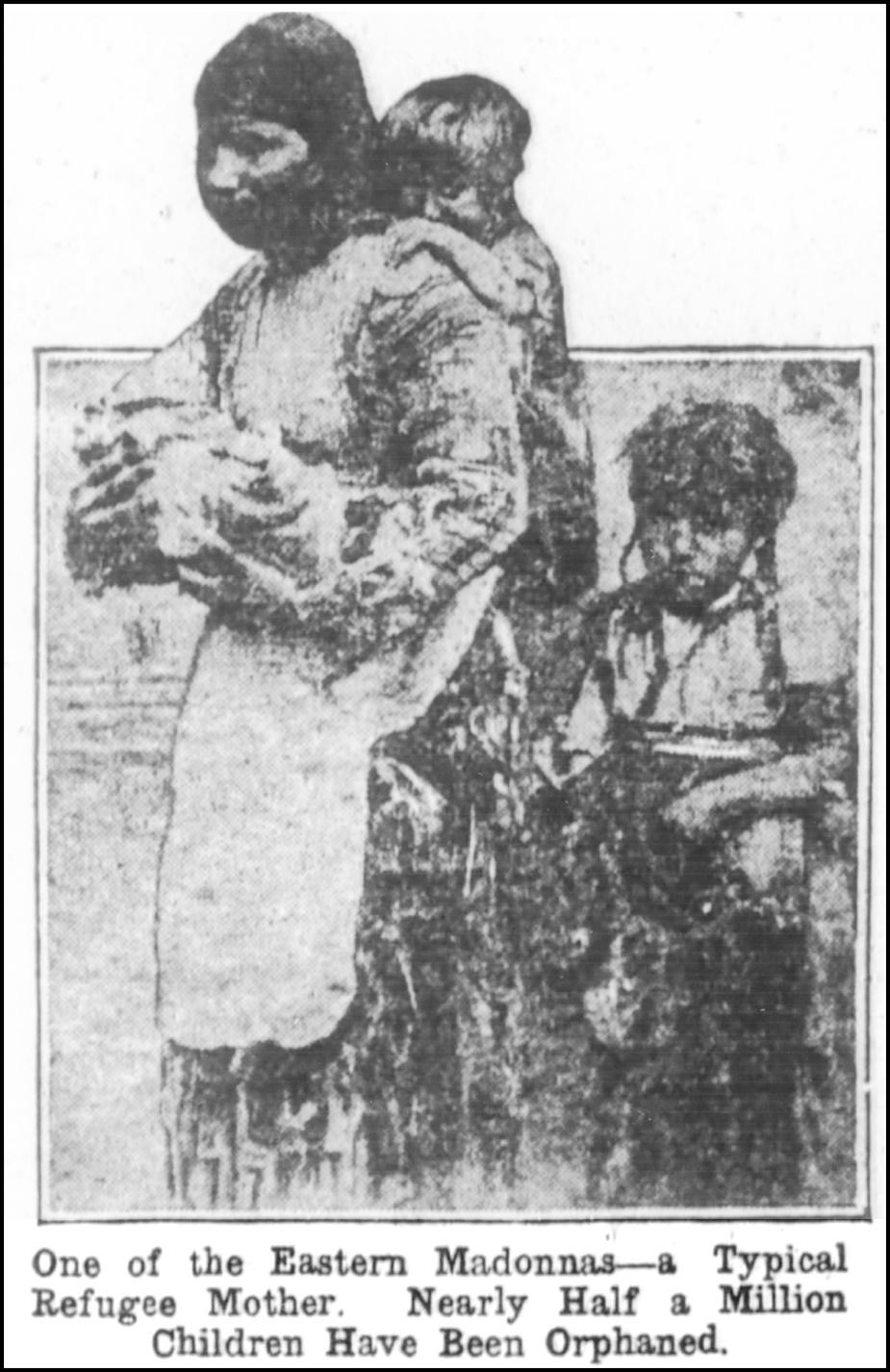

One photograph from the post-Hamidian

massacres period that has special significance in this connection is that of a

very poor Armenian mother with her three children. In the course of our

investigations some years back, we discovered that this photograph was

available online from the Library of Congress Prints and Photographs division.

It was a picture that had special appeal for a number of reasons that we shall

explore, including the fact that downloading was cost-free since it was out of

copyright and the negative was in the public domain. One appreciates at a

glance that this photo shows very graphically the abject poverty of an Armenian

mother and her kids. All are in rags. Their overall condition is deplorable.

Additional to the rags, the mother has

a desperate, forlorn, pitiable and austere look on her face. Despite this, her

general look may be described as stoic. Not much is discernible about her very

young babe in arms even upon close examination. Certainly

one has no idea about the baby other than it must be very young. An older daughter

stands at her side and is clearly very sad. The look on her face will certainly

evoke deep sympathy on the part of any viewer. The child being carried on the

mother’s back, has her right hand on her mother’s shoulder and is peeking out

at the camera. She is a beautiful child and her large, sad eyes straightaway

become a focal point for this painful and distressing photograph (See Fig. 1

below).

When one learns a bit more about the

photograph and the personal family drama it portrays, it assumes a still more

heart-breaking dimension. It is not merely about poverty. It is about some of

the horrible consequences associated with surviving the massacres (and later,

the Genocide), against the Armenians in Ottoman Turkey. It portrays

dramatically the predicament that many women and children found themselves in

when husbands and fathers were killed. This was all the more tragic in a

traditionally patriarchal society. The photo may be taken to represent many, if

not all mothers who were survivors of massacre, genocide and genocidal violence

in any of its several dimensions.

Fig. 1.

"Armenians." Bain News Service publisher. Library

of Congress, Prints & Photographs Online Catalog. Reproduction Number:

LC-DIG-GGBain-27081; Call Number LC-B2-4626-3 [P&P].

In 2010 we published our research about

this sad image online on Armenian News Network Groong. Our delving into this

photograph established that the photograph was taken in Kharpert [Harput city] at the request of American missionaries at the

Eastern Turkey Mission station of the American Board and was to be used in

efforts to attract funding to help with their work with Armenian orphans from

the massacres of 1894 - 1896. We presented as detailed and richly

illustrated an analysis as was possible in view of the information available on

this photograph at that time.

The original photo was first published

in the December 1900 issue of a magazine that went by the name Helping Hand Series sponsored by the

National Armenian Relief Committee which had been set up and operated from

Worcester, Massachusetts. The Helping

Hand Series was overseen and

administered by Emily Crosby Wheeler (1853 - 1936). Her parents were the

pioneer missionaries at Harpoot, Crosby Howard

Wheeler and his wife Anna. (For our complete posted 2010 paper see “Widowed

through Violence, Dirt Poor, Desperate, Burdened with Heart-Wrenching Decisions

Concerning Her Three Children: the appalling woes of an Armenian woman from Geghi [Գեղի] (Erzerum

Vilayet) after the Hamidian Massacres: A publicity photograph of 1899” by

Abraham D. Krikorian and Eugene L. Taylor, Armenian News Network - Groong,

September 7, 2010.

https://groong.org/orig/ak-20100907.html

Our main conclusion was, of course,

that the photograph was not directly related to the horrendous genocide

initiated by Ottoman Turkey against the Armenians in 1915, or any of its

subsequent tragic events and consequences. The image pertained to tragedies

that befell survivors of the Hamidian massacres ̶

widows and children of those many Armenian men who were murdered. (We

will not attempt an analysis of the actual number murdered. It is a contentious

issue that we will not get into here. When we decide to put on our ‘cynic’s

hats’ we generally quip – “LOTS!”)

What’s more, in terms of our learning a

great deal more about the image, we were able to learn the place of origin of

these survivors; even Christian names could be connected with two of the

children. Regrettably there was no record of the family surname.

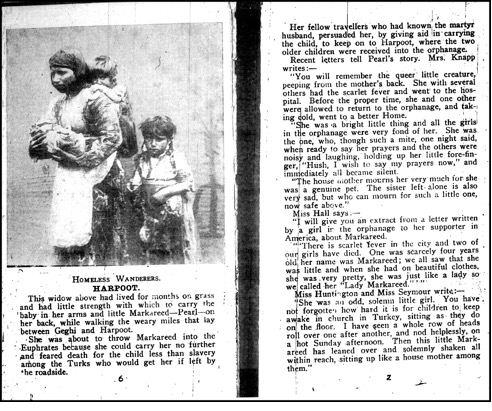

An article entitled “Plea for Armenia”

published in 1909 in various US Newspapers and The Survey magazine (New York, a magazine of social and political

issues, volume 22, May 15, pgs. 249-251) provides a succinct evaluation of the

situation at that time for Armenians in the Turkish Vilayet of Mamouret-ul Aziz [Kharpert province, ‘central’ Armenia]

and, specifically for us and our ‘family portrait because its background

harkens back to the Hamidian and post-Hamidian period in Kharpert.

Quoting from the

article we read: -

“After the 1895 and 1896 massacres,

central Armenia became a veritable field of orphan asylums. Different

missionary organizations, the French Roman Catholic, German Lutheran, the

American missions, established scores of them, at least two in each principal

town, numbering in all in the neighborhood of 150 throughout the interior

provinces….

“Furthermore, there had been for

eighteen months famine in Asiatic Turkey. The 1895 and 1896 massacres, brutal

though they were, did not decrease the supply of breadstuffs, because the

farmers had done their summer work and the massacres came in October. Now

[1909], the disturbances are coming at a critical time. This is the month for

the farmers to plant. Should the seed time go past and another summer’s crop

fail, hunger would claim the country. Long, long before the outbreak of the

current troubles, it has been harassed in two ways that leave it weak. The

Christian is the farmer of Asiatic Turkey. The

famine has not been God’s sending. [our emphasis]

“The

old regime of the sultan is wholly responsible for poor conditions. Bribery

and oppression at the hands of subordinate officials could be traced to his

encouragement. Chiefs of different Kurdish tribes and influential Mohammedans

have forcibly taken away the tillable land from Christians, on one pretext or

another, mainly threatening that they would betray them as revolutionary, men –

which is the biggest fear of the country, - and have turned these tilled lands

into wild cattle pastures. On the other hand, taxation has been growing heavier

and heavier every year. The sultan’s official goes to the poor widow who has

only one son of eighteen, a sole protector and supporter who tills the land

with a yoke of oxen, the only treasures that he owns. The official conducts

away forcibly that yoke of oxen and sells it at auction and leaves him

helpless…”

“Orphanage, famine and poverty – the

toll of the massacre is not complete even with these. We must add sickness. In

1895 in those cities that were along the rivers, the bodies of the dead were

thrown into the water after lying about the streets for a week or more. But in

most of the towns the bodies were left on the ground on the outskirts of the

cities, without burial; dogs ate them and became ferocious, and the decayed

skeletons threatened cholera, had it not been for the approaching winter

season. That winter, half as many as were massacred died of exposure and

typhoid fever.…

“Under the constitution the provinces

were to elect representatives with free votes. Instead, the Turkish officials

threatened the public, especially the Armenians, into casting their votes for

certain Turkish tyrants, most of whom were the leaders of the 1895 massacres.

However, the Armenians succeeded in having eight representatives, two of them

the most able lawyers of their country. During the nine months of the

parliamentary session, repeated complaints came from the provinces that the

usual atrocities were growing worse.”

Readers will know the

rest.

This background provides what we think

is an excellent perspective for our photograph to be understood in a broad and

proper context.

We decided long ago that it was

important to communicate our findings specific to this photo to the Library of

Congress so that proper reference to it could be added to the much too

superficial and quite general description “Armenians.”

We received no acknowledgement from the

Library of Congress but finally, after considerable time, we noticed that the

Library made reference to our Groong posting. The L of C entry accompanying the

photo now reads: -

“Summary:

Photograph shows a poor, widowed Armenian woman and her children, Markarid (on her back) and Nuvart

(standing next to her). In 1899, after the murder of her husband in the

aftermath of the Armenian Massacres of 1894 -1896, the family walked from their

home in the Geghi region to Kharpert (Harput), eastern Anatolia (western historic Armenia,

Turkey) seeking help from missionaries. Photograph was published in Helping Hand Series Magazine (Armenian

Relief Committee) in December 1900 and an image of Nuvart

wearing the same clothes appears in the December 1899 issue of the same

publication.

(Source: http: https://groong.org/orig/ak-20100907.html)

Reproduction

Number: LC-DIG-ggbain-27081

(digital file from original negative. Rights Advisory: No known restrictions

on publication. For more information, see George Grantham Bain Collection -

Rights and Restrictions Information https://www.loc.gov/rr/print/res/274_bain.html.

Call

Number: LC-B2-

4626-3 [P&P

The appeal at that time of the family

‘portrait’- or more accurately ‘fatherless family portrait’ - was clearly very

quickly appreciated by those spear-heading fund-raising efforts for the German

missionary establishment at Mezereh/Harput as well. We described in our original post that the

image was reproduced in 1901 in a German work under the title Deines Bruders Blut, Geschichte aus Armeniens Leidenstagen

[Thy Brother’s Blood, a Story of Armenia’s Days of, Agony, Fr. Bahn,

Schwerin-i. Meckl., our

copy is dated 1900 but quite a few subsequent ‘editions’

or printings were released which do not include the photograph. The ‘editions’

of Deines Bruders Blut with the image that we feature below which were

released at least until 1921 in Schwerin, Germany are rare, even in German

libraries. The “Deutscher Hülfsbund

für christliches Liebeswerk im Orient'' was the

so-called “corporate author” of these and subsequent ‘editions (See http://liberarius.de/verlag-friedrich-bahn/margarete-von-oertzen/).

Fig. 2.

Image of a

desperately poor Geghi family with a minimal

generic-style description provided on the Library of Congress negative.

“Armenian Widow and Her Children.” On the left we see daughter Nonig, her name was formalized by the missionaries, whether

perfectly accurately or not in Armenian, to Nuvart.

This image was printed in Deines Bruders Blut was based on a

photograph that appeared on the cover of The

Helping Hand Series, vol. 2, No.1, December 1899. The image also appeared,

somewhat cropped, on the cover of volume 2, No. 3, June 1900. (We are not sure

exactly where in the Kaza of Geghi

we are dealing with.)

This is probably as good as any place

to mention that we have encountered a few times a Postcard of the Geghi Mother and kids (See Fig. 3 below). The label is

confused and merely states “Arminian Refugees. After the Massacre” [note

spelling error using an “i” instead of “e”] This has

been designated in a published work as deriving from the year 1901 (with no

evidence so far as we can see). We ourselves have not seen anywhere a date of

postal cancellation on a Postcard photograph and thus cannot attest to the

given date when the card was at least being sent, so to say. The card is

numbered No. 239 – presumably in a numbered series of one sort or other. We

have not been able to delve further into this matter. A card was offered on

eBay not that long ago and the selling price was a ridiculous $1000.00 US!

Fig. 3.

“Arminian Refugees.

After the Massacre.” Note the use of the incorrect designation “Arminians” rather than “Armenians.” The spelling Arminian

might bring to mind for some versed in theology adherents to a kind of

Christianity that had nothing whatever to do to with Armenians. But surely, not

very many people would have even heard of “Arminians”

much less who the term represented or their religious philosophy or beliefs.

(As it turns out, the “Arminians” challenged

vigorously the doctrine of Pre-destination adhered to by the Calvinists.)

Details on How Our Image Seems to

have made a leap from relatively poorly known in 1900 to considerably better

known from late 1916 onwards

Lacking any information to the

contrary, we are now obliged to make a leap from 1900 to 1916 as to when one

might encounter use of the Geghi family photograph to

engender sympathy for victims of atrocious genocidal actions against Armenians

in Turkey.

To be more exact, it seems that it was

in the latter part of 1916 that ‘our’ photo of the destitute Geghi family resurfaced. The book in which the photograph

was published was advertised as “newly published” in November 1916. We have no

evidence that the photograph was used earlier than November 1916. The period of

the Genocide is generally taken as 1915 onwards of course. We would not be

surprised to learn that the photograph was used earlier but that question will

have to remain unresolved until something turns up.

In light of where it was published, the

photo certainly would have been accepted as typifying accurately situations

that were widely encountered during the Armenian Genocide. The caption to the

photograph simply reads “Fleeing from Massacre”.

Fig. 4.

“Fleeing from

Massacre.” Scanned from the book In the

Land of Ararat: a sketch of the Life of Mrs. Elizabeth Freeman Barrows Ussher,

missionary to Turkey and a martyr of the great war written by her Father

Rev. John Otis Barrows (1916, Fleming Revell, New York, photograph published

opposite pg. 136.

The key point is that the book was

written by someone who knew quite a lot about conditions among Armenians in

Turkey. The full title of the book is, as given in the caption, In the Land of Ararat, a sketch of the Life

of Mrs. Elizabeth Freeman Barrows Ussher, Missionary to Turkey and a Martyr of

the Great War. It is now rare on the used book market, but it has been

reprinted under the aegis of Trieste Publishing and others. The explanation

given for their reprinting the original volume is “This work has been selected by scholars as being

culturally important and is part of the knowledge base of civilization as we

know it.” It also has been made available online by digitization (See https://archive.org/details/inlandofararatsk00barr).

Although

the volume written by Rev. Barrows (himself a missionary amongst the Armenians

in his early ministerial career) to honor and memorialize his daughter who was

martyred in service in the summer of 1915 was well known by the missionary

establishment, it seems fair to say that the photograph became much better

known during the period of the Late Ottoman Genocides. This later period became

broadly defined as that of “reconstruction” in particular. The picture was used

to represent and describe a typical refugee or genocide survivor Armenian

mother. Some even went so far as to designate her as an example of an “Eastern

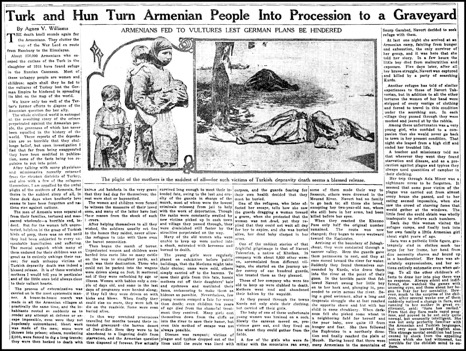

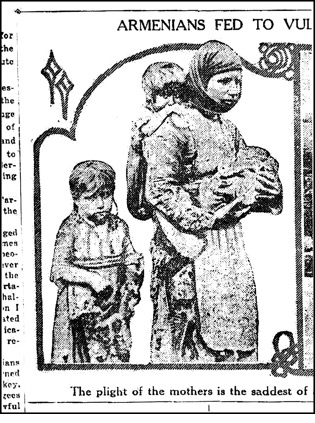

Madonna.” An image in the April 18, 1918 issue of the New York Tribune (NY)

bears the caption “The plight of the mothers is the saddest of all - for such

victims of Turkish depravity death seems a blessed release.”

We

would argue that such a photo would quickly become a dominant image in

imagining and understanding assailed Armenian motherhood in Turkish Armenia.

Fig. 5a.

The 1900 image is on the left side of this picture in this

article in the New York Tribune,

Sunday April 28, 1918 pg. 6 is the 1900 image. Here, the family faces right.

The full, indeed quite detailed, newspaper article, written by Agnes V.

Williams, is entitled “Turk and Hun Turn Armenian People into Procession to a

Graveyard.”

Fig. 5b.

An enlargement of the image with the caption “The plight

of the mothers is the saddest of all ̶

for such victims of Turkish depravity death seems a blessed release.”

Agnes

V. Williams, author of the New York Tribune article shown in Fig. 5a served for

a few years as Editor of New Near East,

the magazine published by the American Committee for Armenian and Syrian Relief

and its successors. She also wrote features for various newspapers.

Regrettably,

we haven’t been able to learn much about Agnes V. Williams. She married Leslie Newlon Hildebrand in February 1920 at her home in

Princeton, New Jersey and gave up her duties at New Near East magazine of The Near East Relief by the end of 1920

after giving three years of service. She certainly was in a very good position

to write an authoritative article on the reality of the Armenian Genocide. She

and her husband Leslie, born in Iowa in 1892, lived after their marriage in New

York City. He was involved in newspaper work ever since the time of his

graduation from the University of Iowa in 1914. His work in New York City was

merely described as that of a publicist. It has been difficult to dig up much

more on that.

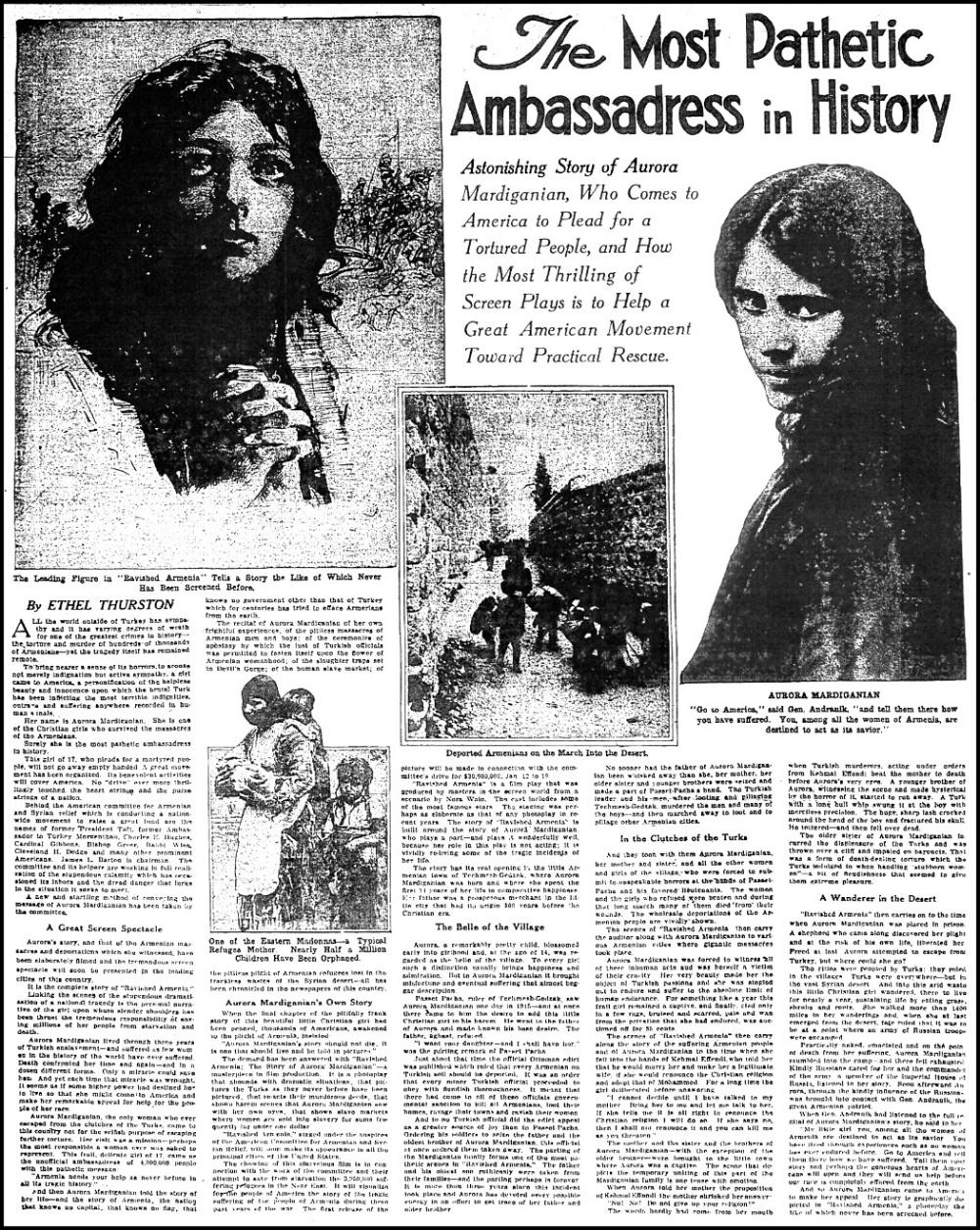

The

Sunday Magazine section of the San

Francisco Chronicle, January 5, 1919 included an image of ‘our’ family (See

Fig. 6a). It is in a full-page treatment and focuses on the events dealt with

or alluded to in the film “Ravished Armenia.” The article title was “The Most

pathetic Ambassadress in History.” The caption to the image reads: - “One of

the Eastern Madonnas ̶ a Typical Refugee Mother. Nearly Half a

million children have been orphaned.”

Fig. 6a.

Scanned from San

Francisco Chronicle, Sunday January 5, 1919, “The Most Pathetic

Ambassadress in History” by Ethel Thurston, pg. 3

Fig. 6 b.

Close-up of the Geghi Mother and

kids shown in Fig. 6a.

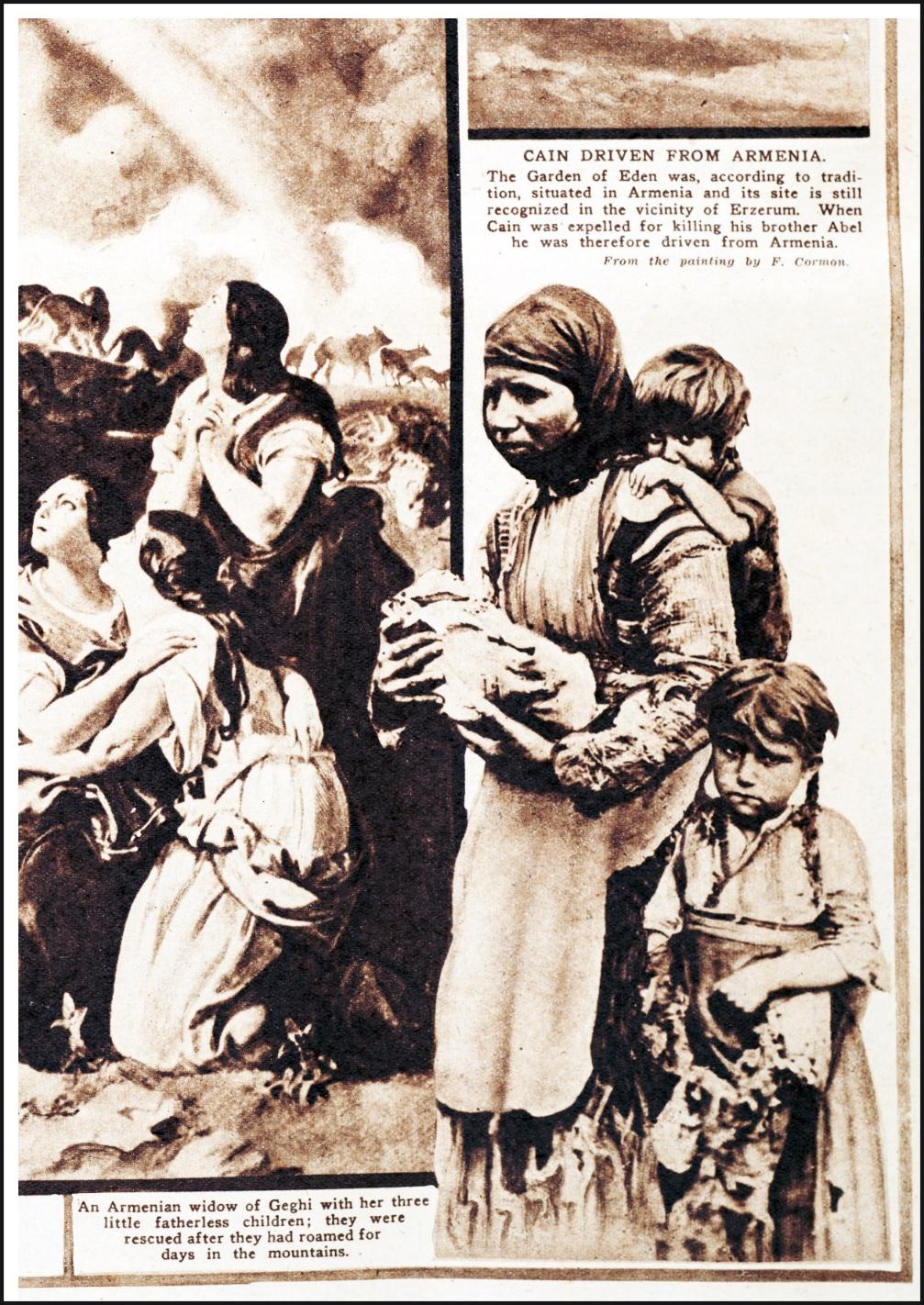

Shortly thereafter, The

New York American for January 19, 1919 included in its Photogravure Section

an image of ‘our’ family captioned “An Armenian woman of Geghi

(we prefer spelling Geghi since it is western

Armenian pronunciation) with her three little fatherless children; they were

rescued after they roamed for days in the mountains.” The two-page spread in

which the photo was embedded is titled “Armenia and the Scriptures, Scenes from

the unhappy land whose people trace their descent from the Family of Noah.” The

photogravure attempts to relate some of the misery at that time, but the only

‘real’ photo included is that of the Mother and children. The other

illustrations are only drawings of a historic nature. The page size of the New

York American was 10 by 17 inches so there would be no problem seeing ‘our’

Mother and kids in some detail.

Fig. 7.

Image of Geghi mother in

original sepia color.

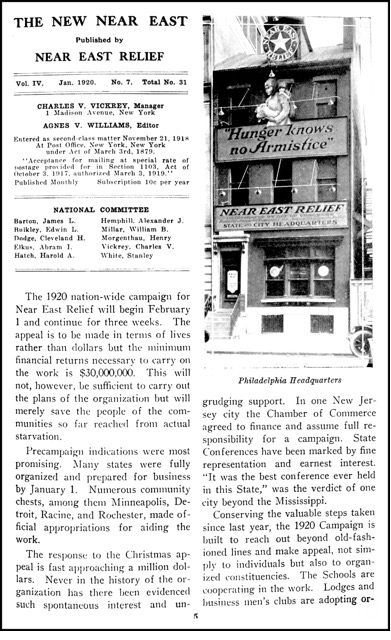

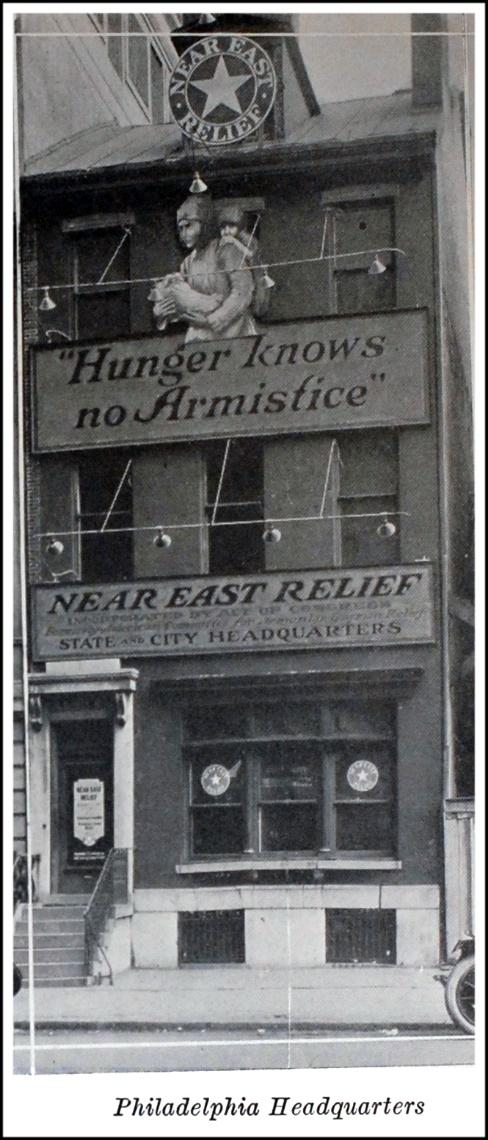

Let us jump ahead a bit further. A year later, in the

January 1920 issue of the New Near East,

one encounters an interesting photograph showing the full front of the building

housing the Campaign Headquarters of the Philadelphia Branch, Near East Relief.

At the upper reaches of the building is a large signboard reminding the readers

that “Hunger Knows No Armistice.” Sticking up from the sign is an image of

‘our’ distraught Mother and her kids. It is a large-scale painting, not a

photographic print. In our opinion, the image clearly was not painted by a

particularly talented artist.

Fig. 8a.

Image of page from the Near

East Relief’s Philadelphia Headquarters.

Fig. 8b.

Cropped image to focus on the imagery (from New Near East vol. IV. Jan. 1920. No.

7, total number 31. Courtesy of the University of Wisconsin Archives who kindly

allowed us to photograph their copy of the issue. There is yet another issue of

The New Near East vol. 6, no.4,

January 1921 pg. 22 that shows the Philadelphia Headquarters with a sign with

‘our’ family that refers to those fronts with elaborate signs for fund-raising

purposes as “a speaking front.”

A

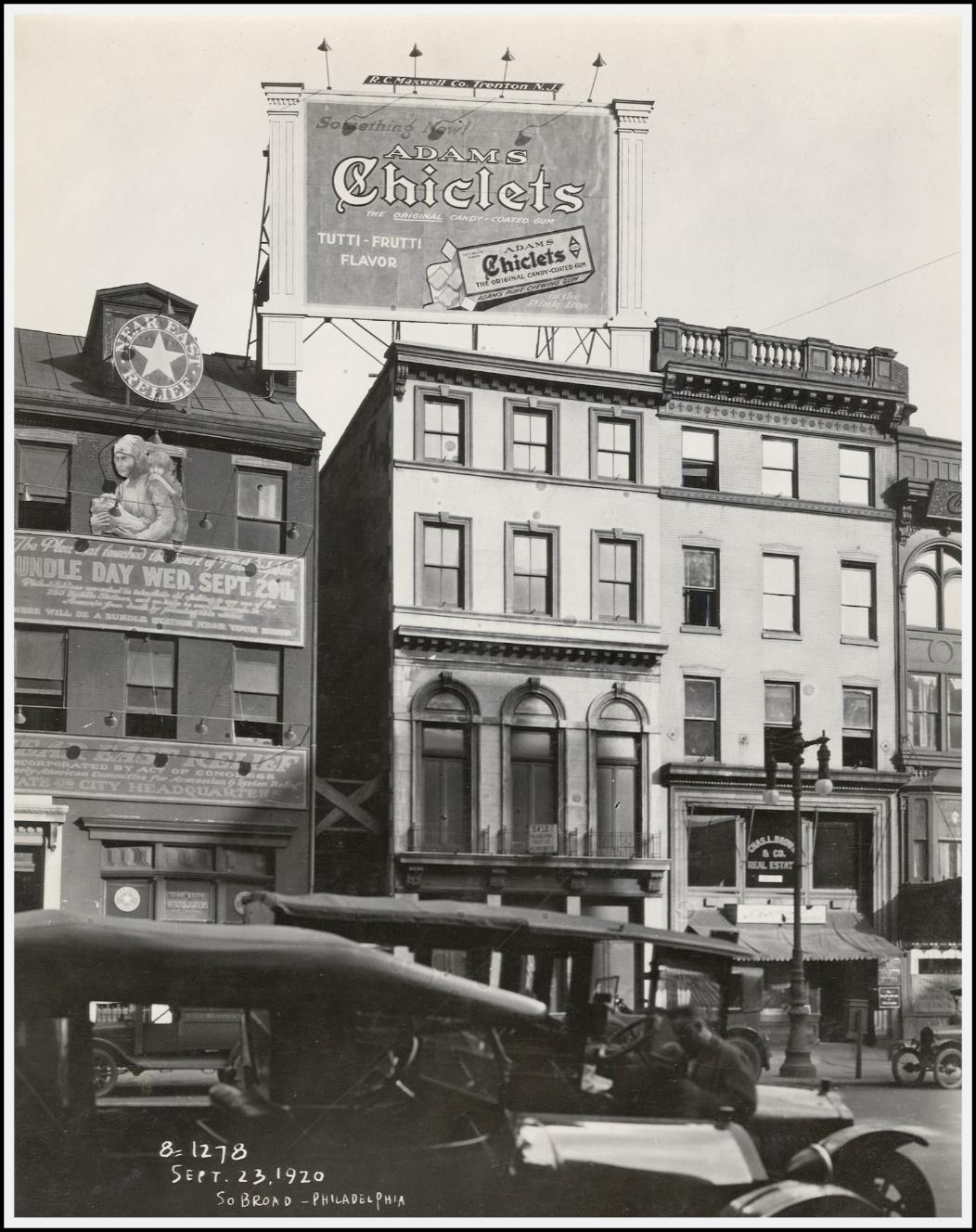

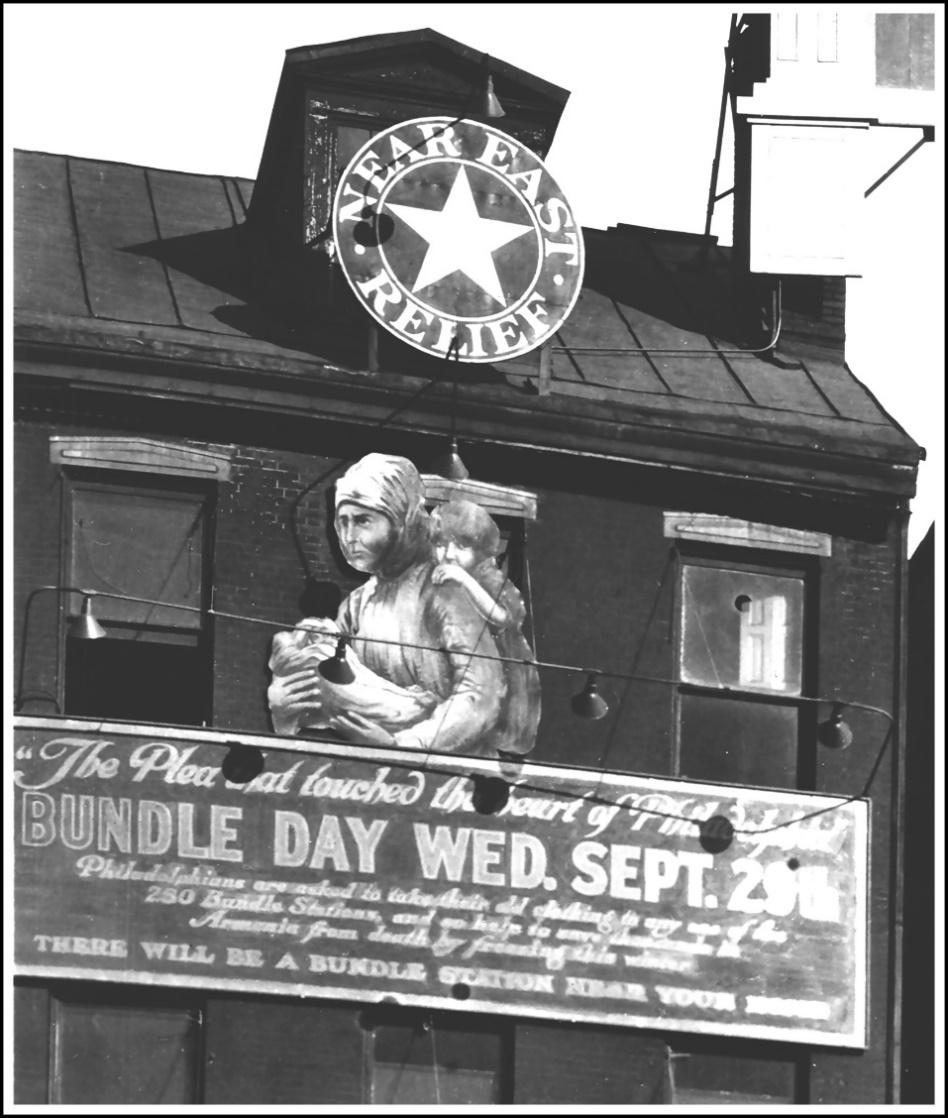

photograph of the building with its sign board may be seen in Fig. 8c below.

Fig. 8c.

Photograph

dated September 23,1920, taken at South Broad Street near Chestnut in

Philadelphia. Courtesy of the R.C. Maxwell Company Collection at Duke

University Archives, Durham, North Carolina.

Fig. 8d.

Close-up of the Philadelphia Headquarters billboard.

Thus, it will be clear to the reader that an appealing yet

sufficiently communicative and horrifying image, justifiably viewed as

well-suited to fund raising for women and children in 1899 - 1900 was retained

for use almost a generation later for survivors of genocide and horrendous

treatment in general, under even more dreadful and vastly more widespread

circumstances. The original purpose in 1900 was to showcase what we would now

refer to as a “before” shot of pathetically destitute children rescued from an

ominous fate that was sure to befall them had they not been ‘saved alive,’ that

is taken in and rehabilitated by the missionaries. The follow-through on this

story seems to have paid no attention to the Mother or the baby. They might

have fallen through the cracks, or arguably more likely, they might well have

become victims of the genocide.

There

is likely no need to belabor the fact that this image has been used over the

years in a very large number of contexts. Inevitably the photograph of the

family is now used primarily in connection with the Genocide of Armenians that

began in 1915.

One

volume in German by the Academic Director of the Lepsius

House in Berlin, Rolf Hosfeld, uses the image of the Geghi family on the cover of a work entitled Tod in der Wüste.

Der Vӧlkermord in der Wüste

[Death in the desert. Genocide in the Desert.] (2015, C.H. Beck, Munich.)

There is a translation into Turkish available [Çӧlde Ölüm: Ermenerilerin

soykırıma uğraması (2008) Eysenyurt, Istanbul put out by ‘Transaction Publishers’

or specifically “Dönüşüm Yayınları” and it appears that the cover

image used is the same one used in the German publication.

Readers

will now know that the image has nothing directly to do with any specific

‘death in the desert,’ or ‘genocide in the desert’ but clearly can serve to

communicate the distress that ‘deported’ Armenian Mothers faced while trying to

‘save’ their young children. The tragic fact is that many Mothers died in the

genocide either through direct murder by convicts released from jails, and by

studied violence, or death from the trials and tribulations of deportation,

hunger, disease and exposure to the elements. A Mother, such as our Geghi Mother with three children would absolutely represent

the exception, and by no means the ‘rule’ to the extent that few mothers could

have saved ‘three’ children.

As

a very relevant aside we bring the Reader’s attention to a posting made back in April 23, 2016 by Krikorian and Taylor entitled “Armenian Immigrants

Rebuilding their Lives in America” https://groong.org/orig/ak-20160423.html.

In that contribution we drew special

attention to the fact that in the photograph taken in Worcester, Massachusetts

of some of the ‘Ashvuntsi’ villagers one could note

the rare circumstance of two ‘Grandmothers’ from the ‘Old Country’ who had

survived the Genocide AND had been able to ‘save alive’ their children. That

was a rarity; indeed, so much so that the grandchildren of these two women were

the only ones we knew personally who had a ‘biological Grandmother.’ One in

particular, became what one might term “a grandmother at large” and was called

‘Granny’ by kids who knew she was not their biological grandmother but were

pleased to have any person they could call “Granny.”

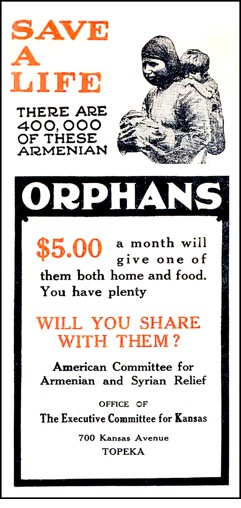

Also,

printed cards with pleas begging “Save a Life” – Armenian orphans were used in

various places, Kansas being one of them, in the ‘reconstruction’ period fund

raising efforts. Fig. 9 below is an image of one.

Fig. 9.

Example of a card used to solicit support.

Because of the inherently generic nature of human

motherhood, we would argue that one can justifiably use the ‘original’ photo in

pretty much any context one wishes.

We have seen that trying to track down the recycling of

the photograph has yielded an interesting history that goes far to defend any

subsequent use to get the message across. The fact is that the most

knowledgeable people, like Rev. James L. Barton who wrote the Introduction to

Rev. Barrow’s book, were involved in promoting the story of victimization. They

never found any problem with the Geghi mother and kids photo.

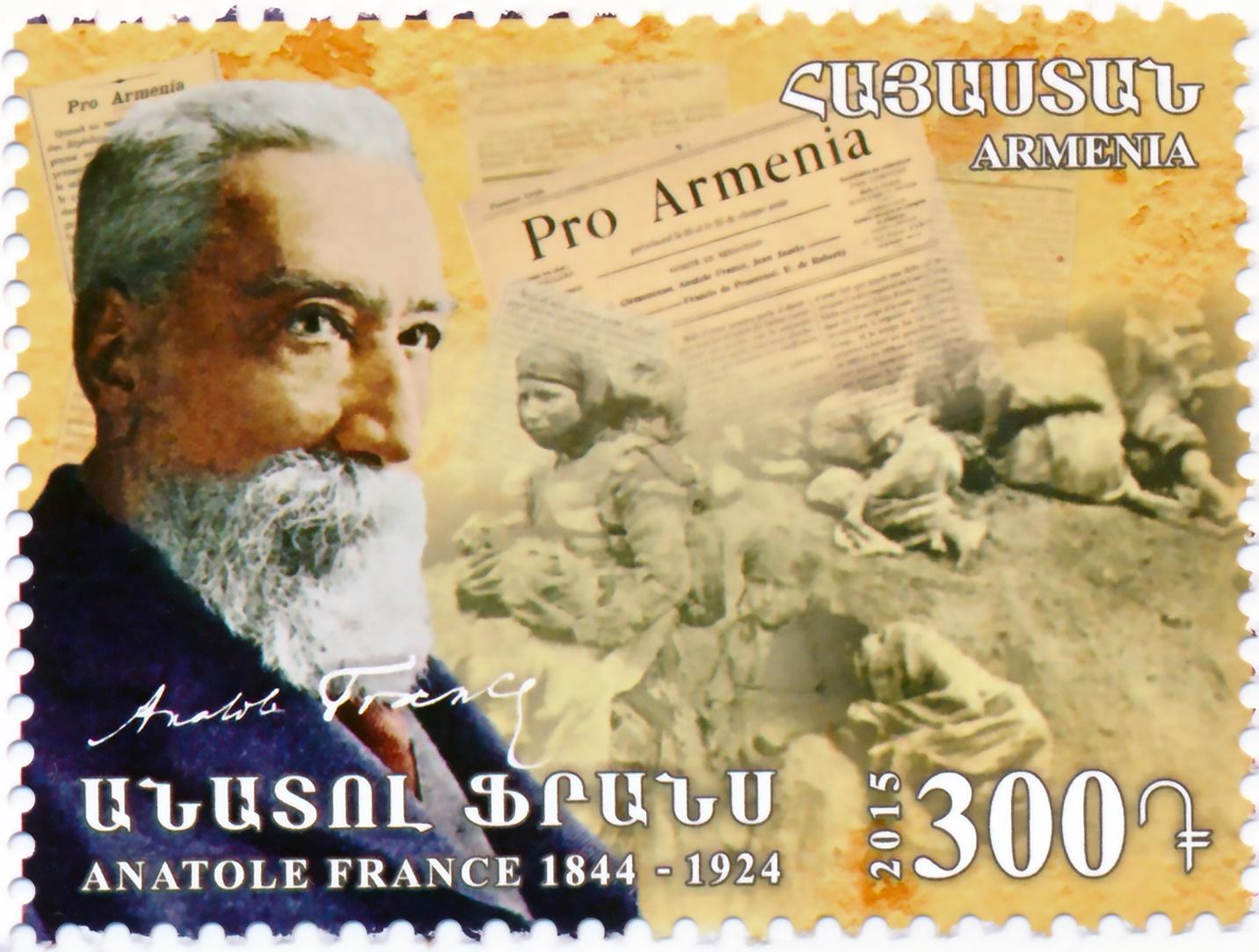

Below

is a 300 dram stamp issued in 20015 by the Republic of

Armenia to honor Armenophile novelist, essayist,

journalist and poet Anatole France (1844-1924) includes an image of our Geghi mother and her children (Fig. 10).

Fig. 10.

Stamp issued 23 April 2015 commemorating the Armenian

Genocide and primarily honoring Anatole France, the famous French man of

letters. The stamp was designed by David Dovlatyan

and Vahagn Mkrtchyan. It is printed by offset and is

40 x 30 mm in size.

In

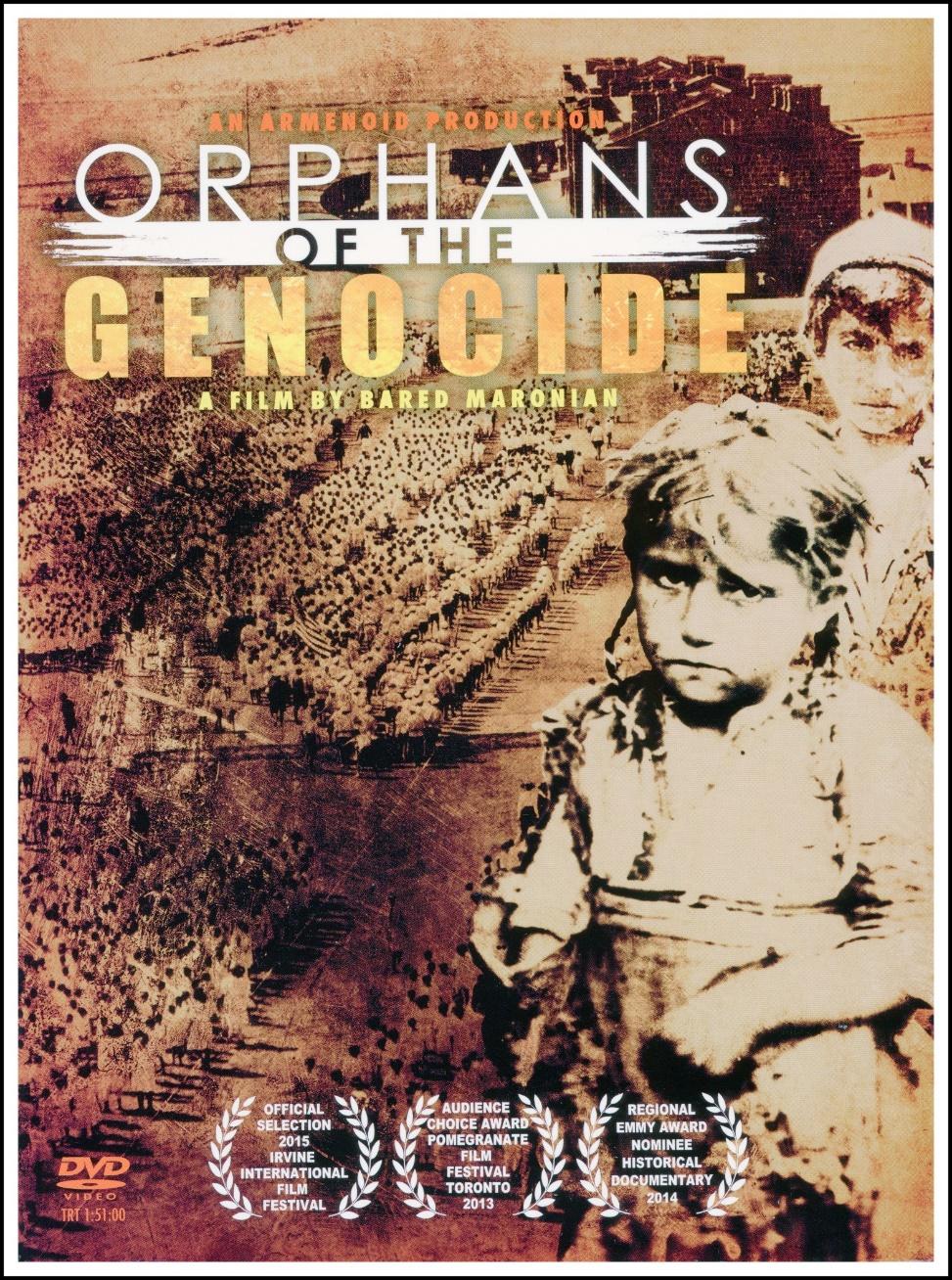

yet another medium, the image of little Markareed of

‘our’ Geghi family was used recently in the outside

packaging of the documentary DVD “Orphans of the Genocide.” Mention was not

made as to the origin of the image. (Fig. 11).

Fig. 11.

Orphans of the Genocide.”

Directed by Bared Maronian,

2013. 91 minutes.

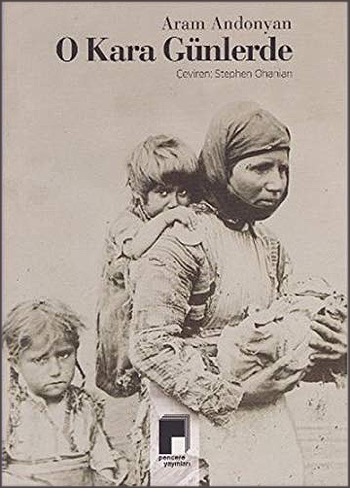

In 2015 ‘our’ family was featured on the soft cover of the

translation from Armenian into Turkish of the 1919 volume by Aram Andonian entitled Ayn

Sev Orerun [Այն սև օրերուն]

– “Those Dark Days” (See Fig. 12). This might well have been the perfect

occasion to use a cover that was more directly synchronized with the events

recounted in Andonian’s book.

There

are certainly many photographs of the genocide (1915 to 1923) available that

get the message across quite effectively. But, “No”, it seems that those who

put out old works with ‘new’ covers prefer to use what they believe is tried

and tested. Besides, why be burdened with copyright or other issues?

Again,

we found no mention of the origin of the image used on the Turkish translation

cover below.

Fig. 12.

Cover of the Turkish translation.

There

is little doubt that the cover used on the Turkish translation derived at some

point or other at the Library of Congress or a copy like it from some other

location.

A

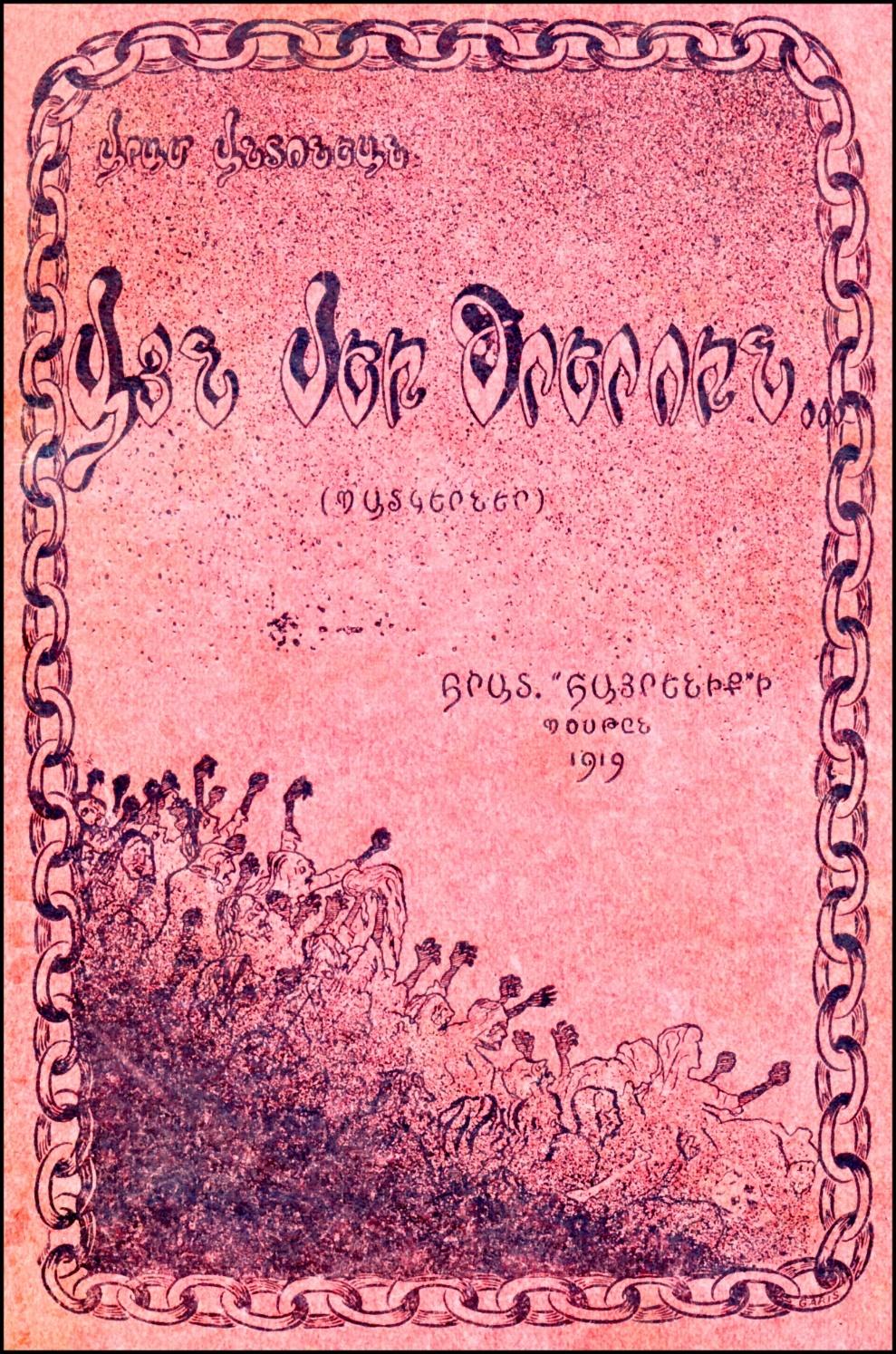

point that we wish to interject here as an aside is this. In our opinion the

original 1919 Armenian language book had an attractive soft cover and it could

have arguably been used to some advantage in any reprinting effort. It would

have reflected accurately, moreover, on tastes of the period. We suppose it is

a matter of preference (Figs. 13a, 13b and 13c).

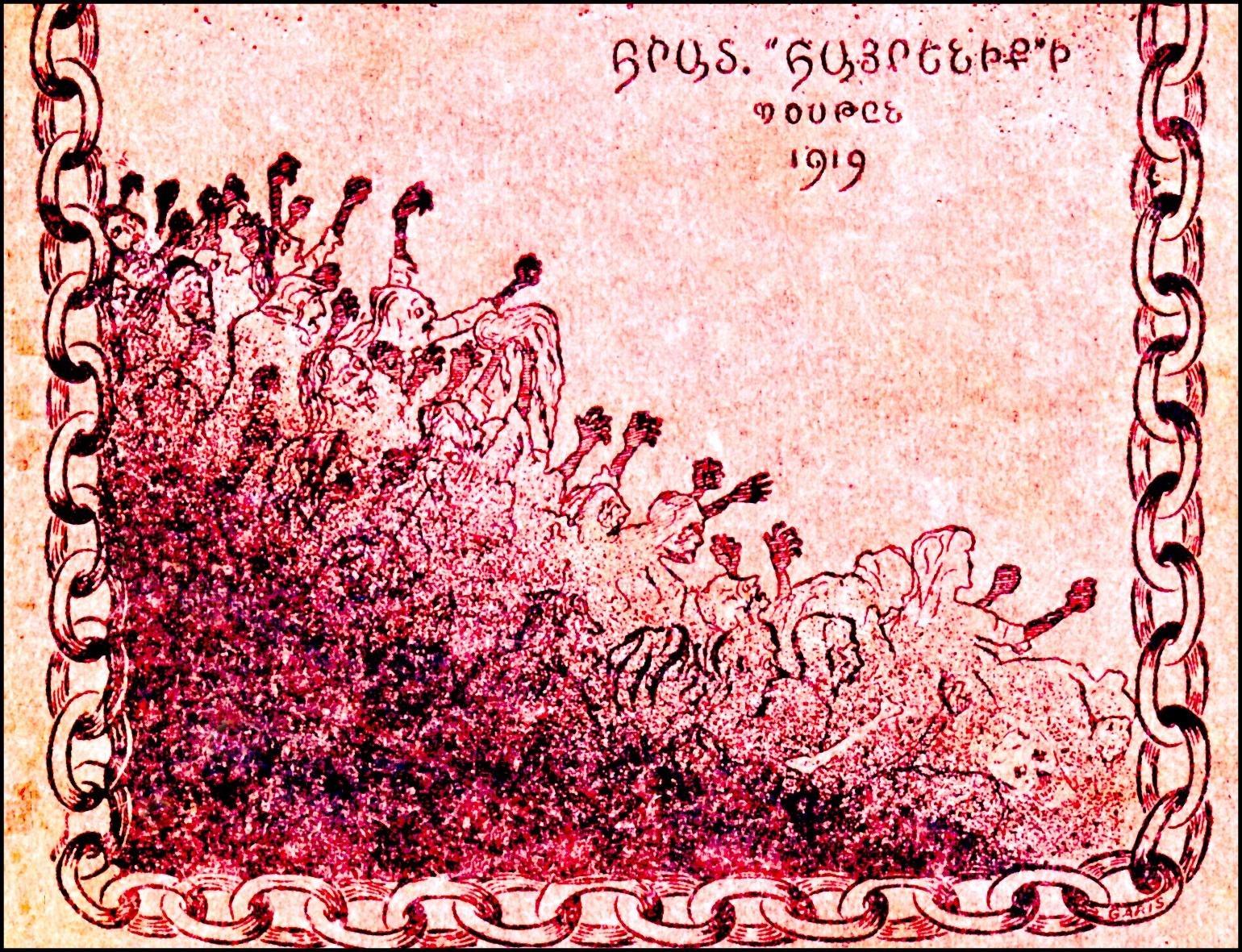

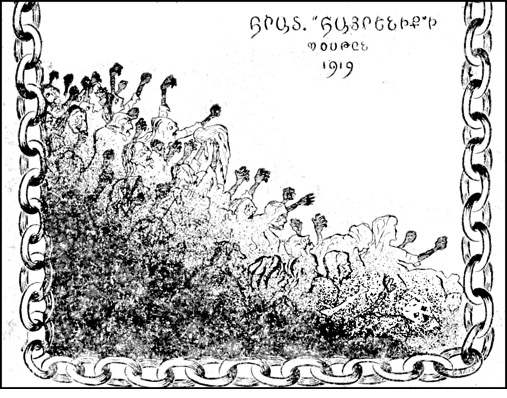

Fig.

13a shows a full-page reproduction of a rare cover on the 1919 first printing.

Fig. 13b focusses on the lowermost part of the page. Note the human skull on

the lower right. Fig. 13c provides the reader with a “desaturated” version of

the colored cover. This helps give a feeling for the cover should one not wish

to go through the expense in printing color.

Fig. 13a.

Cover of the first Armenian edition published in Boston in

1919.

Fig. 13b.

Cover cropped to allow focus on the lower part of the

page.

Fig. 13c.

Desaturated with Photoshop to get rid of color and perhaps

make the image more visible.

Readers

will surely be interested in reading a relevant discourse on Aram Antonean’s book Ayn Sev Orerun by Dr. Khatchig Mouradian article in the Armenian Weekly entitled The Book with a Black cover (See https://armenianweekly.com/2016/01/13/mouradian-the-book-with-a-black-cover/).

Continuing on the use of the Mother and her children

photograph in various settings, it will be noteworthy that some enterprising

entrepreneurs took the initiative a few years ago to produce a picture pendant

locket that featured a colorized image of the Geghi

mother and her children. The colors are vibrant and

colorization added considerably to the attractiveness of the pendant. It seems

that few were produced and it may well turn out that

this item will be appreciated as a rarity. (Figs. 14a and 14b)

Fig. 14a.

Photograph of the pendant.

Fig. 14b.

Close-up of colorized picture pendant.

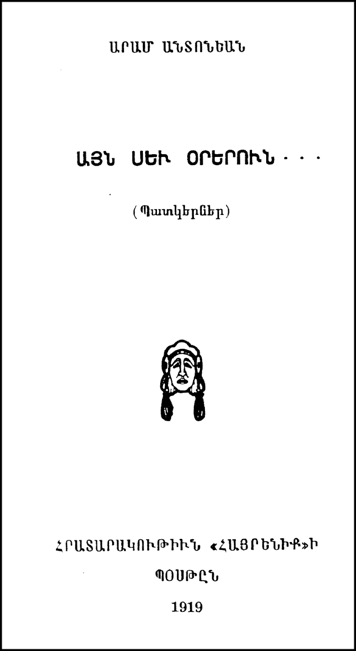

A modern reprinting of the Armenian original book by Aram Andonian – made in India

incidentally, uses a very plain soft cover. The title page put out by the Dashnag “Hairenik” press in 1919

is shown in Fig. 15a. The formal entry

on the cover of the reprint has blunders since it reads “Ayn Sew Rerun: (Patkerner).” We have written to the publishers, Gyan Books

Pvt. Ltd. in India to tell them that a serious mistake has occurred. There is

no word in Armenian as “Rerun” – it should read “Orerun”

(pronounced -oreroon) – meaning days or times. And, the word for black -- sev is

far more accurate than ‘sew.’ Moreover, the ISBN given by Gyan is similarly

botched up. ISBN comprise 10 digits. 13:0 4 4444006 891174 is certainly odd

enough to render it useless.

Fig. 15a.

Title page in Armenian of “Hairenik

Press, Boston, 1919 printing.

Fig.

15b. shows a formal entry of the 1919 volume in the WorldCat.

Fig. 15b.

Copy of the WorldCat entry on

the first edition. The WorldCat attempts to

render all those publications known throughout the world

in various libraries.

There

are sure to be new fresh and imaginative uses of the image, and hopefully new

findings about the photograph will emerge that will allow synthesis of a

detailed time scale as to its publication ‘history’. This should provide still

greater understanding of how it evolved from the post-Hamidian massacre 1899 -

1900 period image to a photograph that is still very much appreciated for being

able to encapsulate at least one crucial aspect of the horrors of the Armenian

Genocide – namely, how difficult it was to show any measure of resilience. The

strength of Armenian motherhood prevailed to the extent it humanly could,

against overwhelming odds. It also emphasizes in no small measure the apparent

resignation of the kids (at least the two in the photograph old enough to feel

the pain) to the care of their mother.

Closing

Commentary

One

might argue that the main take-home lesson from this presentation is that one

should not feel that a specific photograph must be viewed as valuable only if

it can be precisely attested and attributed, that is to say, if it can

accurately be affirmed as to what the photograph represents (attested) and if

the photograph can be identified with a person(s) (attributed). The photograph

may not even necessarily conform exactly to the desired time-period.

In

the case under discussion here wherein a missionary’s father, himself at one

time a missionary, re-introduced an image into the literature of the Armenian

Genocide – whether wittingly or not – and the re-utilization of the image after

apparently being deliberately selected for use in fund-raising by a responsible

body such as the Near East Relief, more than gives some real legitimacy to the

issue.

It

may have been merely the issue of its ease of accessibility. Recall that the

Turkish government did everything in its power to prevent dissemination of

information on what it was doing to the Armenians - especially photographs of

the events!

We

have over the years, repeatedly emphasized those features which might best be

called the “the preferred desiderata” when it comes to selection and use of

photographs. These should be achievable provided some work is put into the

‘project.’ It is certainly to be preferred but as we have seen, not the only

approach.

This

paper essentially constitutes a rather complete paper trail from ‘our’ original

photograph of destitution and need, and its deliberate adoption for fund

raising and educational purposes. To be sarcastic about the matter of need, it

seems to come down to the Yogi Berra cliché “it’s déja

vu all over again.”

We

have provided the reader with a detailed paper trail of the Geghi

Mother and her kids photograph and have hopefully given a broad perspective of

what the Armenian widows and orphans had to go through.

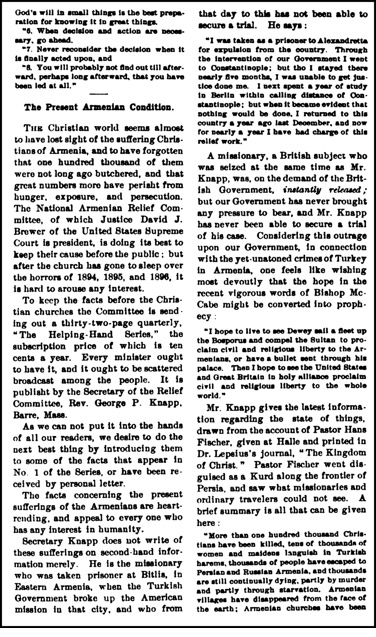

Two

pages from a journal called The Homiletic

Review published in 1899 paint a broad picture. These are shown below as

Fig. 16a and Fig. 16b.

The

pages give not only a broad view of the situation but some very detailed

specifics of “The Present Armenian Condition.” Interestingly, there is some

mention of The Helping Hand Series

that played such a prominent role in getting the story out about ‘our’

Family. Raising funds was no easy task.

What

funds and support that was raised was ALWAYS considerably less than was needed.

Even though this description applies to an area of eastern Turkey, somewhat

remote geographically from Mamouret-ul Aziz, the

actual situation described in detail, is totally applicable in terms of our

needy Kaza of Geghi mother

and her kids.

Fig. 16a.

From The Homiletic Review (April, volume 37,

1899) pg. 384.

Fig. 16b.

From The Homiletic Review (April, volume 37,

1899) pg. 385.

© Copyright 2021 Armenian News Network/Groong and the authors. All Rights Reserved.

| Home | Administrative | Introduction | Armenian News | Podcasts | Feedback |