Armenian News

Network / Groong

“All

Saviour’s Armenian Cathedral, Isfahan, Iran” - a recent addition to our Conscience

Films video site on YouTube. This video will expand some of the imagery presented in the recently

released 2017 calendar by the Diocese of the Armenian Church of America

(Eastern). Some relevant early 20th century photographs of

the dreaded falaka or bastinado (foot torture) are presented as well and

attested precisely.

Armenian News Network / Groong

Special to Groong by Eugene L. Taylor and Abraham D. Krikorian

LONG ISLAND, NEW YORK

January 1, 2017

In

May, 2016 we had a wonderful two-week long trip to

Iran. It was organized by The Nation magazine (first published in

July1865 in New York City). The Nation is the oldest, continuously

published weekly magazine in the U.S.A. Some

37 (mostly mature) Americans - arguably best described as highly educated

and informed progressives - were on the trip.

That in itself added tremendously to our overall

remarkable learning experience. Indeed, the professed mission of The Nation magazine has been to "make an earnest effort to bring

to the discussion of political and social questions a really critical spirit,

and to wage war upon the vices of violence, exaggeration, and misrepresentation

by which so much of the political writing of the day is marred.”

It was totally fortuitous that not long after

our return later in the year from two other trips, one to the Former Yugoslavia

and a visit to Norway, we received the latest Armenian Church calendar issued from

the Cathedral in New York. It was a very

pleasant surprise to see that the theme for 2017 had a focus on Iran. The title of the calendar is: “The Hidden World of Persian Armenia,

BEYOND THE ARAXES”

The

elegant color photographs featured in the calendar were taken by Karapet Sahakyan of Yerevan and

included sites in Iran that we wished we could have visited but these places were

not included on our very compact and full itinerary. For example, lack of free time and distance

precluded our seeing the Saint Thaddeus Monastery complex not far from the site

of the famous battle of Chaldiran, located today in East Azerbaijan province in

north western Iran. Photographs show

that it is a spectacular place in an equally spectacular setting. It has great historical importance in the

evangelization of Armenians by the Apostle Thaddeus very early in the Christian

era.

The

visit to Isfahan, the second most populous metropolitan area after Teheran, was

impressive and particularly significant for anyone interested in the Armenians of

Iran, especially Nor Julfa. The

Cathedral complex and its Museum, which included a section on the Turkish

genocide against the Armenians were highlights. (Many will know that the Armenian church in

Iran is under the jurisdiction of the Catholicosate

of Cilicia and is active on many fronts including publishing and education –

cf. Tchilingarian, 2004 for a succinct presentation

of the various hierarchical Sees.)

We

were so impressed with our visit to what is referred to in Isfahan by

non-Armenians as the “Armenian Vank Cathedral” that

we decided it would be well worth the extra effort to produce our first Iran

video based on it. The video entitled “All Saviour's

Armenian Cathedral Isfahan” can be seen here. The actual URL is: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pfgfKDqgYJQ [Three other videos we have produced on Iran

so far and their respective URLs are “Introduction to Iran – Important

Essentials” https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LVgnr5D8cPU;

“Persepolis: Ceremonial capitol of the Achaemenids and their successors

(located in Fars Province, Iran)” https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RXh3xJb6zI4;

“Ehsan Mohammad Repairs Carpets in his father’s shop (Shiraz, Iran, 2016)” https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=v8h3r_-xqjo

In

the 2017 calendar, Karapet Sahakyan’s

photographs relating to Sourp Amenaprgitch

[Ս.

Ամենափրկչեան]

Vank

complex are to be found at the months of April, August, September and November.

Because

of the sweeping options a video format allows, our film presentation is

considerably more detailed than was achievable in the printed ‘church calendar.’

Our video even includes some key references

to the relevant literature.

Nevertheless,

it is not our intention here to devote attention to the wonderful art work on the walls and in the structure of the Cathedral

proper. References are provided in our Select

Bibliography for those interested in doing more detailed study. [One question

that should come up immediately is the nominally long-standing tradition of

minimal decoration vis à vis art on walls of Armenian

churches. See what the late art historian

scholar Sirapie Der Nersessian (1946) had to say on

that point.]

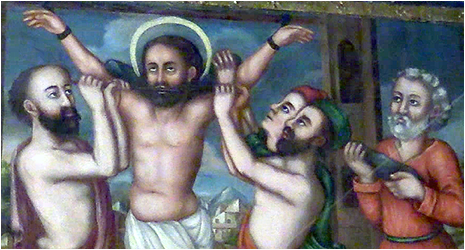

On

the other hand, because some of the wall paintings and frescoes are of particular

interest to the narrative of the espousal of Christianity as a state religion in

Armenia, we will show more than a little detail dealing with the art work portraying the various ‘Tortures of Saint Gregory’,

the patron Saint of the Armenian Church.

These are very relevant to the history of the traditions and portrayal

of Armenian Christianity and its origins as a state religion. [We decided that it would perhaps be best if we depended on Matthew of Tokhat as translated by Malan (1868) in the

literature citations as a source of understanding and explanation for what we

observed. It was all the more attractive

to do this since the book has been digitized and people interested can refer to

it. URLs are provided in our Select

Bibliography.]

We

will also emphasize here and now that it is not our intention to undertake a

scholarly presentation of early Armenian church

history. Myth and tradition, as always,

play a substantial role in such things. Reference

may, again be made to such sources as will be evident from our Select Bibliography.

What

follows are some nine examples of the Twelve Tortures plus one at the end of

the narrative portraying the culmination of the events and the ultimate

acceptance of Christianity by the King Tiridates (Trdat). As it was,

it was not easy to get photographs amidst a throng of visitors. Besides, one will certainly get the feel for

the distinctive, even charming in a morbid way, imagery.

If,

incidentally, anyone feels that he/she would profit by a quick ‘primer’ in the Krikor

Lousavoritch tradition, we recommend that a quick

reading be undertaken of the summary presented in the Appendix at the very end

of this presentation. Otherwise we shall

proceed directly. The plan adopted is to

quote from “The Life and Times of Gregory the Illuminator, the Founder and

Patron Saint of the Armenian Church” [translated from the original Armenian by

S.C. Malan from the original by Vartabed Matthew of Tokat(?)

published at Venice in 1749” (1868).

The

quotes seem to be applicable to what we see in the imagery. While not always a perfect ‘fit’ they are

clearly defensible.

First

torture endured by Saint Gregory

“The

more S. Gregory rose against the abominations of idolatry…the more Tiridates became enraged against him, when shouting aloud,

he said to the saint, “How many times have I commanded thee, O man, not to

repeat these tales, that are not fit to be heard…Thou hast insulted the great

Anahid who supports and protects life in our land, and with her the valiant Aramazd, the creator of heaven and earth; and the other

gods has thou called things without breath or speech. Thou hast also insulted us by calling us

horses and mules; now therefore, as returns for all these insults will I give

thee over to be tormented…Then the king commanded that his hands should be tied

behind his back, and that a bit be put in his mouth, and a heavy lump of

rock-salt upon his shoulders. Then they

made him, thus harnessed and with his face to the earth, run for some time like

a beast of burden, because of his saying to them that they were like horses and

mules, that have no understanding and have no thought

to seek after God. But the saint endured this torture with long-suffering in

hunger and privation, and valiantly by the grace of Christ. (See The Life and Times of S. Gregory,

chapter 7 pgs. 150-151.)

The

enlargement shown below will show the insertion of a bit – which appears

here in the form of a rod.

Second

torture endured by Saint Gregory

“No

sooner had S. Gregory finished his answer, than the king commanded him to be

hung by one foot; then all manner of filth to be burnt under his head, as long

as he thus remained hanging with his head downwards, and withal to beat him

with a heavy green stick. Thus did the

blessed man continue suspended for seven days, during which ten men beat him in

succession by order of the king; while, in addition to the torture of being

thus suspended and beaten at the same time, the stench that rose continually

from under him choked and stopped his breathing…Yet, in the midst of such

horrible tortures, the saint did not even utter a groan, neither did he show

signs of pain; because, raising his mind to God in the deepest and fullest

thoughts of the kingdom of heaven, borne thither by his lofty soul, he was

filled with untold consolation and joy of heart.” (see

The Life and Times of S. Gregory,

chapter 8 pgs. 154-155).

Third torture endured by Saint Gregory

“…the king commanded that two wooden clubs, the size of a

shin-bone, be brought, and then fitted like the bars of a wine-press; then

placing both his legs in between them, they tied them tight with knotted cords,

which they twisted until the blood gushed on the fingers of the men who did it. But the saint continued joyful with wonderful

endurance, magnifying Christ God, so firm and so rooted in the faith of Christ,

as to prefer having his heart of flesh taken out of his body, and giving

himself over to executioners, rather than denying and forsaking Jesus

Christ. While he was so tormented the

king addressed him thus, “How art through Gregory? How bearest thou

all that? Hast thou yet any

consciousness, or feelest thou yet any pain?” Then

answered the saint, “Yes, because I asked the Creator of the world, the Maker

and Framer of all things therein, both visible and invisible, and He gave me

the strength to bear this torture.” (See The

Life and Times of S. Gregory, chapter 9 pgs. 168-169).

Fifth torture endured by Saint Gregory

“Not

only was the king not softened at the sight of so much suffering, but he even

prepared to inflict on S. Gregory yet more cruel tortures, in order, if

possible, to make him do his will respecting the worship of his idols. He therefore commanded to boil together salt,

nitre, and strong vinegar, and all was soon ready; he

then placed the saint on his back, put his head in a carpenter’s vice, and

introducing a reed in each of his nostril, he ordered to pour through it the

horrible matter into each nostril when the saint drew his breath, Thus, while his

head was in the vice they turned the screw with a bar, and poured into his

nostrils, by means of the reeds, the hot mixture of salt, nitre,

and vinegar, in order that, reaching his brain, it might disturb it; and by thus

bringing him to a state of frenzy, to persuade him at last to worship the

idols.” (See The Life and Times of S. Gregory, chapter 10 pgs. 169 ff.)

Seventh

torture endured by Saint Gregory

“…the king commanded a large bag of sheep-skin to be brought,

and be filled with soot from a chimney and with ashes of a furnace. They did not fill it tight, but only so as to

appear full, and only so as to hinder his breathing, for they put it over his

head and tied it round just below his chin, in order that his breathing he

might stuff his nose with the soot and ashes till it reached the brain and

injured him; or if it choked him, well and good, let him be choked. And they left him thus six days. But by the grace of Christ the saint remained

marvelously well and unhurt, nay, he was even strengthened above his other

trials, and with joy glorified Christ God.”

(See The Life and Times of S.

Gregory, chapter 10 pgs. 170-171.)

Eighth

torture endured by Saint Gregory

“The

king, seeing that such tortures of the body could not in any way bend the

saint’s will to the unlawful worship of idols, commanded both his feet to be

tied together, and boiling water to be poured down into his stomach, in order

not only to hurt him, but also to put him to open shame. And the tormentors did as the king commanded

them. — Horrible feeling and passion of the wicked, who were not

satisfied with only torturing him, but with the torture must also cover him

with shame; but he was wonderfully supported in this trial also, wherein he

must have died but for the strength vouchsafed unto him from above.” (See The Life and Times of S. Gregory,

chapter 11 pgs. 174-175).

Ninth

torture endured by Saint Gregory

“…he [the king] became more hardened, until he even excelled wild

beasts and leopards in cruelty. Such was

king Tiridates ere he received the light of grace and

of faith. For although he saw the

wonderful patience of S. Gregory, and repeatedly heard the witness he bore to

the truth, yet never did he reason himself into a better way of thinking. But on the contrary, being yet more

irritated, he commanded him to be hung by his two hands to a piece of wood in

the shape of a cross; then to tie his hands with thick ropes, and his feet

also, like the Saviour Jesus; and then with iron scrapers to tear his sides

until the whole place was sprinkled with his blood.” (See The

Life and Times of S. Gregory, Chapter 12, pg. 177).

Tenth

torture endured by Saint Gregory

“…[the king] commanded a number of iron spikes to be brought in

basketfuls, and to be spread thick over the ground. Then they placed him naked on those spikes,

and dragged and buried him in them, and rolled him about, until his whole body

was pierced through, and there was not a place in it whole. And the earth was sprinkled with his blood

blossomed and budded forth, not with corruptible, passing flowers, but with

incorruptible, unfading plants of faith, and with abundant fruit, as we shall

see shortly. Then said the king to him,

“Where is thy God, Gregory, in whom thou trustest? Will he now come and deliver thee out of my

hands?” But the saint endured his

sufferings with extraordinary patience, and remained alive by the power of God,

praising Christ God with unmingled joy; and all his tortures were easier to

bear than if they had been a pleasure, by the grace of Christ. After this they again cast him into

prison.” (See The Life and Times of S. Gregory, chapter 12 pgs. 176-177.)

Twelfth

torture endured by Saint Gregory

“King

Tiridates having heard the Saint say, that the more

his outward body perished the more also was he renewed inwardly, and that, like

the Phoenix, he came again into fresh existence; and also, that if he, the king

did not turn to Christ, he would assuredly be burnt in the fire of hell that is

not quenched— his wrath was kindled against the saint, and he said, “For

that thou sadist all this, will I cast thee into burning fire, and thou shalt

there be made to know thy deluded state.”

So saying, he commanded to melt some lead in an iron crock and to pour t

upon his body, which was singed and shriveled all over; but he did not

die. They then proceeded to pour some of

it down the mouth of the valiant martyr of Christ; it reached his inward parts,

yet withal did it not kill him, by the strength of Christ. Thus was he strengthened with courage and

fortitude, until it was to him as if water were poured over his body; and it

became evident to all that also in this torture the king’s madness was being

loudly and openly reproved; while bystanders treasured up in their minds all

the saint’s words touching the service and fear of God.” (See The Life and Times of S. Gregory,

chapter 13 pgs. 182-183.)

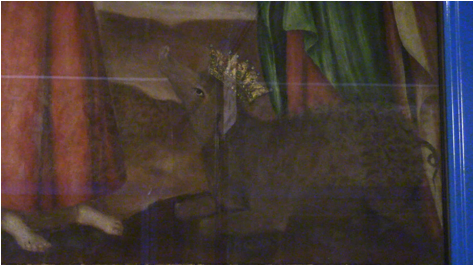

It is in this last panel that we see the

King portrayed as a boar wearing a crown.

King Trdat’s wife Queen Ashkhen

and sister Princess Khosrovidoukht appear here as

well.

Being

completely enthralled, King Trdat III made

Christianity the official religion of Armenia.

See Appendix for details. Also we

recommend that the contribution of Hayk Hakobyan (2012) listed in the

bibliography be consulted.

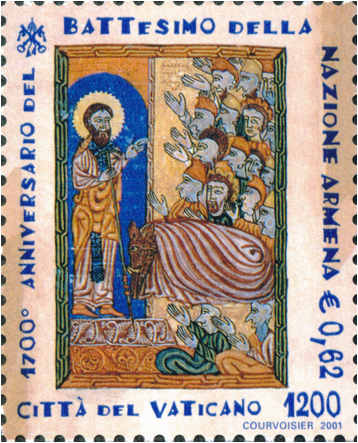

A

manuscript image from 1569 A.D. of the soon-to-occur or forthcoming cure of

King Trdat from his mental illness wherein he perceived

himself a wild boar is portrayed on a 31 X 37 mm stamp issued by Vatican City

in commemoration of the 1700th anniversary of the conversion of

Armenia to Christianity. The 1200 lire

(ca. 62 cent) stamp, printed in Switzerland by Helio

Courvoisier, was issued on 15 February 2001 as one of three dealing with the

anniversary. The description in the

stamp catalog describes the scene as “St. Gregory the Illuminator prepares to

give human qualities to King Tiridates who is

portrayed symbolically as a boar.”

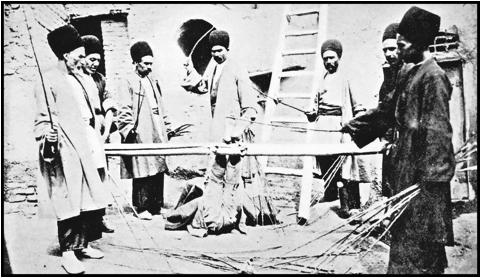

MAKING

A FINAL, ALBEIT MODEST CONNECTION WITH IMAGERY AND TORTURE

We use

the Tortures of Saint Gregory to Say a Bit about

Photographs of the Falaka or Bastinado (foot torture) in the early 20th

century.

Some

of us (one of the present writers, ADK) are familiar with the bastinado, or

falaka (in Turkish) from a very personal perspective. ADK’s Great Grandfather Khatchadour Tashjian

had been subjected to the falaka to such an extent that he could thereafter barely

walk for a very long time. The Turkish

authorities had come to the village of Kerope in Kharpert to get information on

one of Khatchadour’s sons who had been drafted and

escaped from service. He honestly

reported that had no knowledge but he was nonetheless taken to Mezireh and severely

interrogated. ADK’s mother recalled that

his feet were incredibly swollen. Her

Grandmother, Gultana, expressed relief that her

husband had not been subjected to the torture whereby fingernails were pulled

out. Strange to us, fingernail removal

was apparently more liable to infection than feet made raw by falaka.

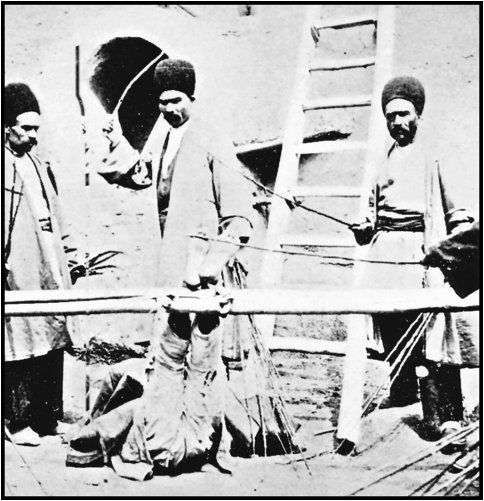

There have been, on occasion, photographs used that

nominally show the falaka being administered.

Hofmann and Koutcharian (1992) provide a copy of the photograph shown

below.

They point out that “This photograph too has frequently and

incorrectly thought to pertain to the Genocide of 1915. In fact, it does not show a torture scene in

the Ottoman Empire, but rather a case of bastinado in Iran, where this sort of

corporal punishment was, as in many Eastern countries, a component of the

“administration of justice.” The

clothing of the men standing up clearly identifies them as Iranians. Possibly Wegner took the photograph when he

went on a short excursion to Iran from Soviet Armenia at the end of 1927.” It gives the provenance as the “Armin Wegner

collection.”

We have identified this photograph as from Wilson’s (1906)

Mariam. A romance of Persia (1906) published by the Young Peoples’

Missionary Movement [American Tract Society] in New York. It is to be found between pages 20 and 21.

Clearly Wegner did not take the photograph. Where he obtained the photograph in his

collection is not clear but he may have used it in his illustrated talks, hence

it was in his photo collection.

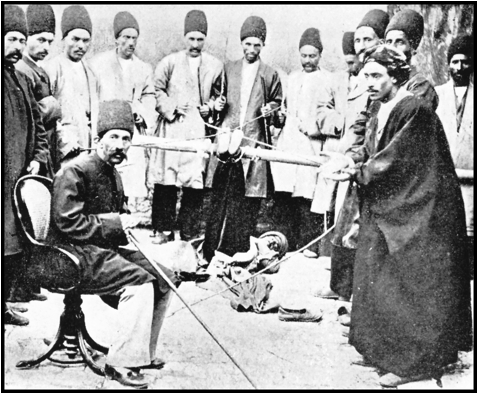

In

a somewhat earlier photograph shown below we see again the falaka being administered

in Persia. We scanned the photograph

from Piolet and Lamy (1901, pg. 188).

We

have not encountered photographs of the falaka being administered in Ottoman

Turkey. But admittedly, neither have we

gone out of our way to track any down.

The use of falaka has, of course, been used in Turkey even in modern

times. For instance there are details of

its use in a Middle East Research and Information Project report (MERIP

Reports) (Anonymous, 1984). Here the

subject was a Kurdish lawyer acting on behalf of PKK (Kurdistan Workers’ Party)

‘clients.’

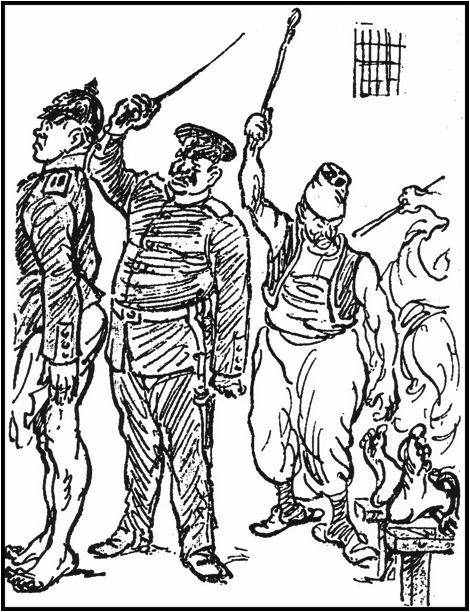

Despite

the paucity of photographs, there are a fair number of cartoons depicting

falaka. The one below derives from the

satirical daily Le Charivari (Paris)

November 22, 1914. It was entitled L’Alliance Germano-Turque [The

German-Turkish Alliance] and has the added caption “Qui se ressemblent

s’assemblent” [‘birds of a feather stick together’]. On the left hand side of the severely cropped

whole we see German discipline with a cane on the buttocks; on the right side, the

falaka is being administered to bare feet shackled down.

SELECT BIBLIOGRAPHY

Agathangelos/ Agat`angeghos

(1980, 1909) “Patmut`iwn Hayots” [History of the

Armenians].

A

facsimile reproduction of the 1909 Tiflis edition in Classical Armenian, with

an introduction by Robert W. Thomson. (Caravan Books, Delmar, NY). Deals with political events and the

Conversion of Armenia to Christianity.

Anonymous (1984) Document. The torture of Hüseyin Yildirim. State terror in Turkey.

Merip Reports No. 121. February, pgs.

13-14.

Ashjian, Mesrob Vartapet, Arpag Mekhitarian et al. (1975) Album, All Saviour’s

Cathedral, New Julfa, Isfahan. [Text and captions of photographs in Armenian, Persian, English and

French]. A

Publication of the Diocesan Council of the Armenians in Iran and India.

(93pgs.)

Carswell, John (1950) A

seventeenth-century typological cycle of paintings in the Armenian Cathedral at

New Julfa. Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld

Institutes vol. 13, no.3/4 pgs. 323-327.

Carswell, John (1968) New

Julfa: the Armenian churches and other Buildings. Oxford at the Clarendon

Press.

Carswell, John (1981) New Julfa and the Safavid Image of the Armenians, pgs. 83-104, in “The Armenian Image in History and Literature,” ed. by

Richard G. Hovannisian, (Undena Publications,

Malibu).

Der Nersessian, Sirapie (1946)

Image worship in Armenia and its Opponents. Armenian Quarterly (New York) 1, 67-81.

Hakobyan, Hayk (2012) Adoption

of Christianity in Armenia: Legend and reality. In: “Ireland and Armenia:

studies in language, history and narrative”, pgs. 151-168, ed.

by Maxim Fomin, Alvard Jivanyan and Seamus Mathuna. Institute for the Study of Man, Washington,

D.C.

Matthew of Tokhat,

translated by Malan, Solomon Caesar (1868) The

Life and Times of S.

Gregory the Illuminator, the founder and patron saint of the Armenian Church, London: Rivingtons.

Accessible in its 1868 edition at

https://archive.org/details/lifeandtimessgr00mattgoog

or

https://books.google.com/books/about/The_Life_and_Times_of_S_Gregory_the_Illu.html?id=LYJDtCXwZSoC

or for a pdf file, merely introduce you’re your

browser

https://ia801209.us.archive.org/13/items/MalanSaintGregory/Malan_Life_of_Saint_Gregory.pdf

See especially pages 150 to 226 for a

description of the twelve “tortures endured by Saint Gregory for the sake of

Christ, out of love for Him.”

These pages provide great detail and

enable one to interpret accurately the panels that are especially important

from the perspective of the adoption of Christianity by the Armenian nation.

Garsoian, Nina (1982) The

Iranian Substratum of the “Agathangelos Cycles”. In “East

of Byzantium: Syria and Armenia in the formative period,” Nina G. Garsoian, Thomas F. Mathews

and Robert W. Thomson, eds., pgs. 151-174, (Dumbarton Oaks, Center for

Byzantine Studies, Harvard University, Washington, D.C.).

Garsoian, Nina (1994) Reality and myth in Armenian history. In:

“Church and culture in early medieval Armenia”, XII, pgs. 118-145.

Aldershot, Brookfield, MA. [Appeared first in Studi Orientali dell’Università di Roma ‘la Sapienza’ 13 = The East and

Meaning of History. International Conference (23-27 November 1992) Rome (1994)]

Ghougassian,

Vazken S. (2005) The Emergence of the

Armenian Diocese of New Julfa in the Seventeenth Century. (Scholars Press, Atlanta).

Hakhnazatrian, Armen

and Vahan Mehrabian (1991) Nor/Julfa. Documents of Armenian Architecture No.

21 (Venice, OEMME). [in Parallel English and Italian, 123 pgs.]

Hewsen, Robert H. (1985/6) “In

search of Tiridates the Great.” Journal

of the Society for Armenian Studies 2, 11-49 (see especially at 20 ff. The

Conversion of the King)

Hofmann, Tessa and Gerayer Koutcharian (1992) “Images that Horrify

and Indict”: pictorial documents on the persecution and extermination of the

Armenians from 1877 to 1922. The Armenian Review 45 (no. 1-2/177-178) pgs. 53-184. [See especially at pg. 183, Fig. 117.]

Kouymjian, Dickran (2005) The

right hand of St. Gregory and other Armenian Armenian

Relics. pgs. 221-246. In: “Les Objets

de la mémoire: pout une approche

comparatiste des reliques et de leur culte”.

Ed. by Philippe Borgeaud and Youri Volokhine, Peter Lang,

Bern.

Landau, Amy S. (2012) “European religious iconography in

Safavid Iran: decoration and patronage of Meydani Bet’ghehem (Bethlehem of Maaydan)”,

in: Iran and the World in the Safavid Age,

edited by William Floor and Edmund Herzig, pgs.

425-446. I.B. Tauris, London.

Meinardus, Otto

(1971) The Last Judgments in the Armenian

Churches of New Julfa. Oriens Christianus vol. 55 pgs. 182-194.

Nersessian, Vrej (2001) Treasures

from the Ark: 1700 years of Armenian Christian Art. (British

Library, London). See especially pgs. 19-24 in

particular for Armenia’s conversion to Christianity.

Piolet, J.B., ed. and Lamy,

Etienne (1901) Les Missions Catholique françaises au XIX siècle. A.

Colin, Paris. Vol. 1, p. 188 especially.

Russell, James R. (1987) Zoroastrianism in

Armenia. Harvard Iranian Series, Volume 5, Published by

Harvard University, Department of Near Eastern Languages and Civilizations and

National Association for Armenian Studies and Research. (Distributed by Harvard

University Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts and London.)

Ter Hovhaneants,

Harut’iwn T. (2008) Patmut`iwn Nor Jughayi (iSpahan), vii, 655 pgs. Armenian

Press at Vank Cathedral Isfahan. [reprint of Պատմութիւն Նոր

Պատմութիւն

Նոր Ջուղայու

որ հԱսպահան, 2 volumes 1880-1881]

Tchilingarian,

Hratch (2004) The Catholicos and the

hierarchical sees of the Armenian Church. In: “Eastern Christianity. Studies in Modern History, Religion and

Politics” (pgs. 140-159, ed. by Anthony O’Mahony, Melisende (London).

Thomson, Robert (2001) The Teaching of Saint Gregory.

Agat’angelos: Gregory. The Illuminator Saint.

Revised edition. St. Nerses

Armenian Seminary, New Rochelle, NY.

W. Van Lint, Theo Maarten (2010) “The Formation of the Armenian Identity in the First Millenium.

In “Religious Origins of nations? The Christian communities ofthe Middle East”, ed. by

Bas ter Haar Romeny, pgs. 251-290. Brill, Leiden and Boston.

Wilson, Samuel Graham (1906) Mariam. A

romance of Persia. Young Peoples’ Missionary Movement [American Tract Society] New

York.

Accessible online at https://archive.org/details/cu31924029348277

APPENDIX

It could easily be argued that the last few images shown are

the most important in the Church. Some

might even say it symbolizes the crux of the message of that we tried to

capture in our video in its entirety.

The images cover the story of the Patron Saint of the

Armenian Church Krikor Lusavoritch (in English Saint

Gregory the Enlightener).

One of the earliest ecclesiastical historians Salminius Hermias Sozomen (lived ca. 400-450 A.D.; English translation of his

work dated 1855 available online wrote in his Chapter VIII – How the Armenians and Persians Embraced

Christianity

“The Armenians were the first to embrace

Christianity. It is said that [King] Tiridates [III] (Tiridates is the

Greek form, the Persian or Armenian form is Trdat), the sovereign of that nation, was converted

by means of a miracle which was wrought in his own house; and that he issued

commands to all the rulers, by a herald, to adopt the same religion. I think that the introduction of Christianity

among the Persians was owing to the intercourse which the people held with the

…Armenians: for it is likely that by associating with such divine men they were

stimulated to imitate their virtues.” pgs. 63-64.

Armenia was indeed the first country to adopt Christianity

as the state religion, this was around 301 A.D.,

pre-dating the Edict of Milan put forward by Emperor Constantine the Great of

the Holy Roman Empire in 313 A.D. The

Edict of Milan was in effect an edict of toleration whereas Christianity was

imposed on Armenians by regal fiat. In

fact, it is stated that Emperor Constantine himself did not espouse

Christianity until he was on his deathbed in 337 A.D. (A few modern historians opt for 314 A.D. for

the conversion of Armenia although Church tradition has long set it as 301 A.D. Either date gives the Armenians the

distinction of being the first nation to adopt Christianity.)

It remained for Emperor Theodosius to make Christianity the

official religion of the Empire in 380 A.D.

The

story of Gregory does reflect a miracle of course, and bits of this dramatic

story, which in it whole is rather long, are worth recounting because they show

how important Christianity is for the Armenian national identity.

To make a long story short, Gregory entered into service of

King Trdat (romanized form Tiridates). Gregory

was a faithful servant to the Zoroastrian King but refused to give up his

Christianity. Gregory’s famous statement

of rejection of conversion is “If thou expel me from this life, thou dost send

me to the joy which Christ has prepared for me.” The King asked

“Who is this Christ of thine? Will he

loose thy bonds?” Since Gregory showed

no signs of submission, the King ordered him to be cruelly tortured until he

should give way.

He did not recant and the levels of torment and torture can

be viewed in the panels. The various tortures are described by the early historian of Armenia,

Agathangelos, who actually was Tiradates private

secretary. In the

well-appreciated book The Conversion of

Armenia to the Christian Faith by William St. Clair-Tisdall

(1897) says the tortures were too horrible to recount. Viewers will agree that some of the panels portray astonishingly wicked

torments.

As if these were not sufficient, the King decided to commit

Gregory to a pit (called Khor Virap, or

deep pit inhabited by serpents and other vile creatures located in Armenia)

where he would suffer even more cruel torments, this time in darkness and still

greater misery.

The story goes that during his imprisonment Gregory had been

kept alive by the kind intervention of a Christian widow who lowered bread to

him every day. Miraculously he survived

the trials and tribulations of being in the pit dungeon.

Almost as soon as Gregory had been sent into the pit there

took place a widespread persecution of Christians throughout the known

world. Roman Emperor Diocletian seems

to have set the example and King Trdat took up the

call.

We will not go into detail on the persecution by King Tiridates of some 37 nuns headed by an abbess named Gayane who had fled Rome and gone to Armenia in search of

refuge after one of their number, Hripsime, reputed

for her outstanding beauty, indeed supposedly as the most beautiful woman in

the Roman Empire, was chosen to be wife for Diocletian in a one-sided

‘romance’.

When Emperor Diocletian learned of their escape to Armenia,

he was outraged. Orders were sent to

Armenia, then a suzerain state of Rome, that the fugitives were to be found and

slain although he suggested that the King might himself elect to marry Hripsime. Her

vehement refusal and escape ended in all the nuns being hideously

murdered. They were not even allowed

burial. (Magnificient

churches in classical Armenian architectural style were built in the name of

both Gayane and Hripsime

who were canonized by the early Church.)

Now comes the consequences for King Tiridate’s

wicked dealings and doings.

We are told that his conscience gave him no peace and he

soon became insane; the same for many in his

circle. The rather unique form of the

King’s madness was that he imagined himself to be a wild boar. (Psychiatrists have referred to this form of

schizophrenia as lycanthropy. The

form in which more usual clinical manifestation of this kind of schizophrenia

is usually as a wolf—as in ‘werewolf.)

Be that as it may, it seemed that there was to be no cure achievable by

usual means.

The King’s sister Princess Khosrovidoukht,

secretly a Christian, had a dream in which she saw her brother’s illness cured

by Gregory — and only by

Gregory.

Thus, after about twelve or thirteen years in the pit

Gregory was brought out and, again to make the story short, miraculously effected cures.

As said

in the text, being completely enthralled, King Trdat

III made Christianity the official religion of Armenia.

|

Redistribution of Groong articles, such as

this one, to any other media, including but not limited to other mailing

lists and Usenet bulletin boards, is strictly prohibited without prior

written consent from Groong's

Administrator. |

| Home | Administrative

| Introduction

| Armenian

News | World News | Feedback |