Armenian News Network / Groong

Winter in Kharpert area: how much detail do we have on the

use of a ‘kourss’ to keep the family warm in winter?

March 7,

2016

Special to

Groong by Abraham D. Krikorian and Eugene L. Taylor

LONG

ISLAND, NY

Some of us

recall growing up as first-generation American Armenians and being chided by

non-Armenians about the very strange habits of ‘the Armenians.’ ‘They’ “wash” their bread [in reality, only dampening

with tap water to render pliable a piece or portion of dry flat bread - referred

to as chorr hahts, pahts hahts, parag hahts [Endnote 1,

at end of paper]; ‘they’ “eat sour

milk” [madzoon or yogurt, pronounced yogh’ourrtt by

Armenians who spoke Turkish, and has become widely used tho’ often

‘camouflaged’ with fruit] and what is ‘really’ weird is that ‘they’ “take

bricks to bed in the winter” to keep warm!

The “bricks”

referred to were, as some of us will know as kiremits [frequently pronounced kihre’mid

by Kharpert villagers [2] that were

usually carefully selected for its composition

̶ that is, the “brick” had

to deemed appropriate for heat-conservation and slow-release. They were flat and rectangular in shape and

after heating made great bed warmers.

Ordinarily,

these “bricks” were light clay-colored, and in America at least, they often derived

from furnace boiler-liner clay tiles or even chimney tiles. In any case, they were NOT ordinary red-color

construction “bricks” that we are generally familiar with nowadays.

Their

shape and thickness gave ample surface area and made the kiremits warm up fairly quickly in an oven. After neatly wrapping the heated kihre’mid, first in a few layers of

newspaper and then placing into a flannel bag or wrapper, they served as an

efficient bed- and great foot-warmer for hours on a wintry night. They gradually cooled and were only really cool

or spent out by morning — no electric blankets in those days!

As an

aside, but an important aside, one of us (ELT) remembers his grandmother in

small-town Kentucky heating a brick on the radiator, wrapping in flannel and

using it the same way as a kiremit.

In the Old

Country, or the Erghir [yergir, erkir

etc.] the usual rural housing arrangement was such that heat from the farm animals

helped considerably to break the cold since the stable or akhor was part of the house and located either next to the living

quarters or beneath the living quarters.

Using thermal energy from oxen, cows and other animals is sometimes touted

as ‘modern’ or at least an innovative concept.

And, a few villages in the Old

Country were apparently comprised of homes that were often fully or partially fashioned

into hillsides, and had full earthen ‘roofs’.

This should ring a bell as well and sound familiar to Americans as “earth-sheltering”

or “dug-out housing.”

Unfortunately,

when compared to other cultures subjected to detailed study by anthropologists

and sociologists, there has not been that much written in great detail about

Armenian domestic culture insofar as housing for the peasantry or for that

matter those better off financially is concerned. So far as we are aware at least, there is not

that much more available for those in financially better positions. [3] In fact, we have read missionary

accounts that draw attention to the fact that homes of the wealthy could not be

differentiated from the outside from those of the relatively poor.

Kiremits were used in the Old Country for keeping warm

under the yorghan. [4] That is for sure, but the ‘kourss’

was used while sitting about before going to ‘bed.’ Interestingly, the word and concept of the ‘kourss’

seems to be less well known and certainly the kourss is far less frequently

encountered in photographs.

Availability

of some relevant ‘kourss’ photographs has prompted us to share them here.

But before

we delve a bit into some details of our special topic of ‘the kourss’ it may be

well to show some photographs that emphasize that the Kharpert region did get snow,

and on occasion the snow amounted to a substantial amount.

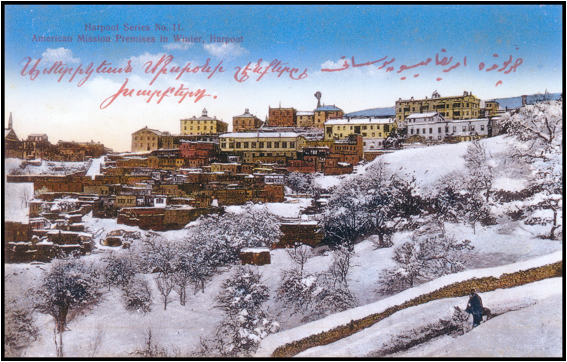

The color

view of Veri Tagh [upper precinct or ward] Harpoot [Kharpert Kaghak] presented in

a Post Card below will be fairly familiar to many though this, scanned from an

original, is presented in higher resolution than those we have seen elsewhere.

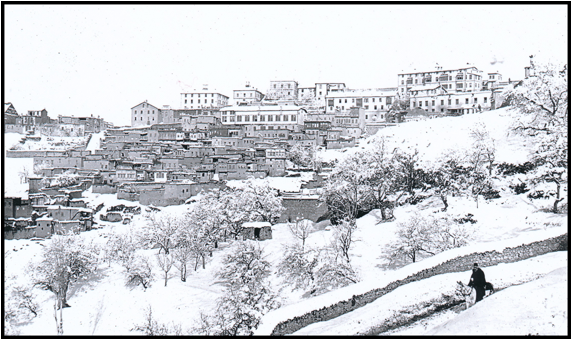

The

original black and white photograph shown below and from which the colored Post

Card was generated will be generally unfamiliar. We cannot claim to know how many of these ‘black

and whites’ are ‘out there’ but the ‘original’ or contemporary photograph has

to be quite rare. The photograph we show

here is not simply the product of converting a color image to a black and white

through Photoshop or the like.

Photograph of Harpoot

and the Euphrates College area taken by Ernest W.[ilson] Riggs, President of

Euphrates College. Riggs was President

of Yeprad College from 1910 to 1915, so the photo would have been given to Louise

Carroll Masterson, Consul Masterson’s wife some time before 1914 when the

Mastersons left Harput to go to the Consul’s new posting at Durban, South

Africa.

The

photograph from which this copy was made was among the items given us by the

late Mary C. Masterson. Her father, William

W. Masterson, was the penultimate United States Consul to Harput,

Turkey-in-Asia. He served at “Harput”

so-called although the actual Consulate was in the lower ‘twin’-city provincial

capital of the Vilayet of Mamuret-ul-Aziz, Mezireh. [5] Masterson, trained as an attorney, was an effective Consul but many

will be much more familiar with the name of his successor. Leslie A. Davis, also a lawyer, was present

as the genocide unleashed against the Armenians by the Young Turk government

unfolded. He communicated through

telegraphic dispatches with the American Embassy in Constantinople, i.e.

Ambassador Henry Morgenthau, and wrote a detailed final report that he

submitted in early 1918 to the Head of the US Consular Service. This report, which was requested by the Head

of the Service, is an exceptionally valuable document on specific events

written by an official of the United States Government, which never did declare

war on the Ottoman Government. [6]

The

photograph shown below shows a winter scene in upper Harpoot city. The photograph was taken near the residential

buildings associated with Euphrates College. This photograph comes from a

private collection to which we were kindly given access and may be dated as from

the winter of 1915 or 1916 or 1917 or 1918.

We cannot

take the trouble to say much here about Mrs. Masterson except to say that she

and her husband came from the small town of Carrollton, Kentucky with which one

of us (ELT) is very familiar and has deep family roots. Carrollton is on the Ohio River, not far from

Cincinnati. The Mastersons are all

buried in Carrollton. [7]

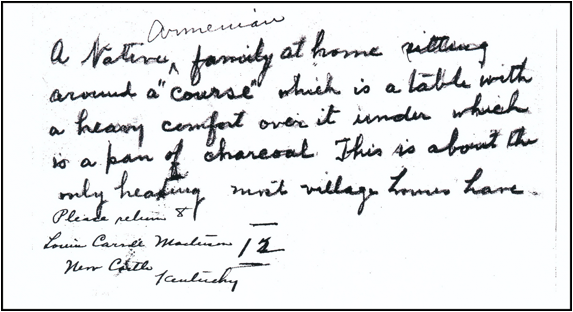

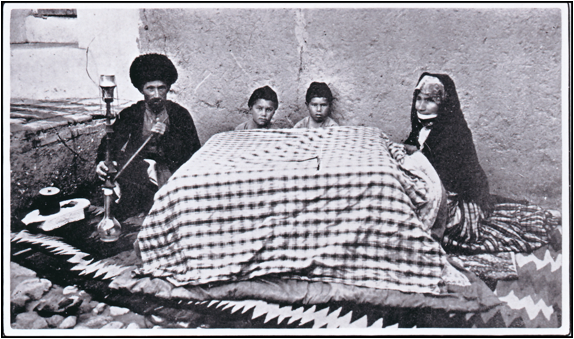

It is

noteworthy that it was a dozen years ago or so that we saw a photograph of what

was designated as a “course.” And as we

shall soon see, it was described rather clearly on the back of the photograph. It was indeed a photograph showing what a ‘kourss’

as described by ADK’s mother looked like.

We hasten

to say that use of the kourss [8] is described but not specifically

named as such in Villa and Matossian’s “Armenian Village Life before 1914”

(Wayne State University Press, 1982). Those

writers describe the mangal, which “could

be used for heating or for cooking. It

was a type of brazier, a deep earthenware or iron pot with a screen over the

opening, handles, and ten- to 12-inch legs.

Finally, a comforter could be thrown over a screened-in fire and still

provide enough room for several family members to sit under it and be protected

against the cold.” (Cf. Villa and Matossian, 1982 pg. 34.)

Louise

Carroll Masterson’s photograph is shown below and is followed by a scan of the

back of the photograph describing the scene.

“A native Armenian

family at home sitting around a “course” which is a table with a heavy comfort

[a now dated word equivalent to comforter]

over it under which is a pan of charcoal.

This is about the only heating most village houses have.” “Please return Louise Carroll Masterson New Castle

[,] Kentucky” [9]

The

Masterson photo description is in keeping with what was described to ADK by his

mother years ago. ADK never heard of a screened-over fire being used. It would be good, of course, to have exact

details on any variants. [10]

Centralized

heating of any sort was not a thing available to the masses, of course, and the

kourss is to us a great example of

how clever a method this was. Couple

this with the body heat of some animals, tucked in on/under a wool-filled yorghan, a kiremit and a prior exposure to the comforting warmth under or

beside the “kourss” what more could one want? Necessity is the mother of invention, and no

doubt the generally resourceful villagers had things worked out ages ago.

We have

only encountered a couple of photographic representation of a “kourss”. The one below was published in Rev. James

Wilson Pierce’s “Story of Turkey and Armenia” (1896 pg. 418). The caption reads “KOOR-SE IN ARMENIA.” There is nothing in the text that tells us

what a ‘koor-se” is or does. If

perchance anyone finds a place in the text that we have missed any mention,

however skimpy, of a “koor-se” we should appreciate learning it. [11].

From “Story of Turkey and Armenia, with a full and accurate

account of the recent massacres written by eye witnesses” edited by Rev. James

Wilson Pierce. D.D. (R.H. Woodward Co., Baltimore, 1896)

Another

image may be seen in a 1906 book entitled “Mariam, a romance of Persia” by

Samuel Graham Wilson (American Tract Society, New York following pg. 30).

This is

captioned “Abgar and family seated at the kurisee.” On pg. vii there is a glossary of foreign

words and there the kurisee is described as “a table over underground oven”.

“Abgar and Family Seated at the Kurisee”

It may be

that this photograph is more in keeping with the description given by Villa and

Matossian (1982)? But the “course” of

Mrs. Masterson and the “kourss” of ADK’s mother seems that it has a bit more

potential for better control of heat and might be a hair safer. Some of the medical missionaries commented

that children got injured and burned by accidentally coming in contact with the

tonir or clay- walled oven in the

floor.

Last but

by no means least, we present below a photo of a “mangal” brought back from

Sivas by Near East Relief worker, Mary Hubbard.

It shows

how elegant mangals could be. A number

of years ago we saw a few huge, elegant mangals on exhibit at a museum in

Alexandria, Egypt. They were really

works of art. When we asked the guide

accompanying us whether what we saw in a corner was in fact a mangal, we were told that indeed it was and

that the word mangal, used by us,

actually derived from the Arabic word manqal.

A Mangal from Sivas polished after being brought to America

by Mary Hubbard.

We thank

Araxi Hubbard Dutton Palmer for access to this photograph. A smaller black and white version of this

photograph may be found on pg. 140 of her book “Triumph from Tragedy” (Privately

printed, 1997) [12]

Closing Commentary

Specifics

on day-to-day life in the Erghir accompanied by great detail are in relatively

short supply. Efforts to locate photos,

or better yet to locate real items used ought to be a priority. Stories of everyday life might then be told

in enough detail so one does not have to allude to generalities that do not

stand up to rigorous scrutiny. All would

hopefully agree that it would be nice to use imagery that makes sense, and

which is based on fact rather than assumptions.

Endnotes

Endnote 1. Literally translated as ‘dry’,

‘open’ or ‘thin’ bread respectively — (all of these have long-since

attained gourmet status as flat breads and wraps) — in Worcester one

never heard the word lavash bandied

about],

Endnote 2.

A few Armenian immigrant families were surnamed Kiremidjian, variant

spelling Kiremitjian and so on. The last

name signified that somewhere along the line a male ancestor made clay

‘somethings or other’ ̶ roofing tiles [in those situations where they

were actually used -- most roofs were flat.

The root of the word is said to be Greek; the Turkish -ji ending found in many Armenian last

names -signifies ‘maker of’ or

‘seller of’, ‘worker of’ – e.g. Tashjian, a stone cutter or worker, or

gravestone maker, a mason etc. The

Turkish ‘tash’ means stone or rock.]

Endnote 3:

We will hopefully be forgiven for referring to a paper in German by an

Armenian. We are sure there are others

but this is a really good presentation.

Parsadan Ter Mowsesjanz (1892) “Das armenische Bauernhaus. Ein Beitrag zur Culturgeschichte der Armenier.”

[The Armenian farmhouse: a contribution to the cultural history of the

Armenians] in Mitteilungen der

Anthropologischen Gesellscahaft in Wien. New Series 12, pages 125-172 with 55

illustrations in the text.

Endnote 4.

The ‘yorghan’ [Turkish for quilt although also referred to by village

Armenians as yorghans as well, and/or

as angorhin [or ungorhin] in Armenian. These

were quilt-like comforters, usually of brightly colored cotton fabric

–sometimes red, filled with wool and sewed with huge stitches of thread

or string to keep the wool from ‘wandering’ within the coverlet and thereby

yielding a heavyish comforter of unequaled cosiness. Unlike an eiderdown goose feather-filled comforter,

which is infinitely lighter, the yorghan is not light in weight. The yorghan

could serve either or both as mattress and coverlet blanket—the latter

being referred to as a dzadzgots [blanket

or covering].

Endnote 5.

See our “Massacres Averted in Mamouret ul Aziz [Kharpert] in April 1909:

A Specific Incident at Itchme and the Role of United States Consul William

Wesley Masterson” on Armenian News Network / Groong, December 16, 2009. http://groong.usc.edu/orig/ak-20091216.html Consul William W. Masterson was succeeded by

the better known Leslie A. Davis whose Final Report to the US Consular Service

was published in edited form as “The Slaughterhouse Province.” Also in this connection, see our “United

States Consul Leslie A. Davis’s photographs of Armenians slaughtered at Lake

Goeljuk, summer of 1915” in Festschrift Wolfgang Gust zum 80. Geburtstag (ed.

by Muriel Mirak-Weissbach, pages 169-197, Dinges & Frick, Wiesbaden.)

Endnote

7:

See our appreciation of Mary in “Mary C. Masterson, Daughter of Harput

Consul William W. Masterson, Dead at Age 92” posted

on the Armenian News Network / Groong, on June

11, 2007. See

http://groong.usc.edu/orig/ak-20070611.html

Endnote 8.

The spelling “kourss” adopted here is arbitrary, of course, since we

have not seen the word printed in a dictionary. Our English spelling is based on well-recollected

pronunciation. We leave it to others to find in a dictionary. In any case, as mentioned, the use of the kourss for warming the family inside the

village home had been described the proverbial ‘hundred years ago’ in fairly

specific terms to one of us (ADK) by his mother.

Endnote 9.

We suspect that Mrs. Masterson sent this photograph to someone who wanted

to use it, possibly in a publication. It

has a number on it and this suggests as well that it was only one of several

photographs sent. Some of the

“Masterson Photos”

appear in J.

[Hagop] Michael Hagopian’s “Voices from the Lake” (Armenian Film Foundation

2000). Mary Masterson told us that her mother had

sent photographs to “some Armenian on the west coast” but could not recall

who. Whether they were copied and

returned or retained is unclear. No

credit is given as to the source of some of the stills used by Hagopian. There is little doubt in our minds after

careful consideration that some of the photos in “Voices from the Lake” derived

from the Masterson’s camera. The

“course” photograph shown here by us does not appear in the film.

Endnote 10. The charcoal was used sparingly. Apparently on occasion some so-called komur [coal in Turkish]/adzough [in Armenian] would be used

instead of charcoal. Some will be

familiar with the expression of Kheljoo

gragh Kharpertsi — a Kharpertsi who was poor to the point of having

to use or build a very meagre fire — or as we have referred to it, as being

“flaming poor”. In any case, one can be

sure that the heating used was by no means exorbitant. After all, the villagers were necessarily very

frugal. One figure we have seen that

shocked even us is that around 1905, a peasant in eastern Turkey would make as

wages the equivalent of about 12 cents a day!

Endnote 11.

The scan presented comes from our personal copy of the volume. The scan available on the Internet copy is, as

is the usual case, quite poor – see https://archive.org/details/storyturkeyanda01piergoog

While we

have been impressed and pleased over the years that many works have been

scanned and made available to readers at no cost, the images are very bad

– perhaps necessarily (?) bad. We

started our work on ‘genocide-related photographs and imagery’ in earnest years

ago. This was before such whole book scans

were being thought of, much less made available in any quality- good or bad. Viewers will hopefully agree that a good

quality scan from a volume in hand is not only considerably more attractive to

look at but more useful for study than as a printout from a digitized relatively

low-resolution version. Those who insist

300 dpi is sufficient do not know what they are talking about so far as we are

concerned.

Endnote 12. See “Triumph from

Tragedy” (1997, privately published). See

also our Araxi Hubbard – amazing story of an Armenian Orphan at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=D7sL1Wl7qJ0

(February 6, 2014) and our “An Orphan of the Armenian Genocide: A Valentine’s Day

Armenian Poster Child” (February 14, 2014) on Groong Armenian News Network http://www.groong.org/orig/ak-20140214.html

|

Redistribution of Groong articles, such as

this one, to any other media, including but not limited to other mailing

lists and Usenet bulletin boards, is strictly prohibited without prior

written consent from Groong's Administrator.

|

| Home | Administrative | Introduction | Armenian News | World News | Feedback |