Armenian News

Network / Groong

A Family Photograph from Korpeh,

Kharpert, Old Armenia Bears Forceful Witness to the Genocide

Armenian News Network / Groong

July 10, 2015

Special to Groong by Abraham D.

Krikorian and Eugene L. Taylor

Long Island, NY

“Photography

discovers, recovers, reclaims, and at unsuspecting moments, collaborates with

the creation of what we call history.”[1, Endnotes]

Most have heard or read somewhere along the line that the Armenian

Genocide is “hotly debated.” We have

often wondered why those who supposedly debate this fact so hotly are oftentimes

unidentified – ‘the Turks and a handful of their lackeys’ for sure –

who else debates it other than those who have an agenda, hidden or otherwise?[2]

Dr.

Levon Marashlian, Professor of History at Glendale CC put it very aptly some

years ago: “The Ottoman government slaughtered and starved the Armenian people

to death. Today’s Turkish government

seeks to stall and “study” the genocide’s history to death.” Or, as Professor Gerard Libaridian put it several

years earlier, well before his becoming a Professor at the University of

Michigan: “The Armenian Genocide is not a historiographic problem, it is a

political one.”

We personally have many reasons not to worry too seriously about all this.

And like virtually all readers of Groong,

we know what Drs. Marashlian and Libaridian have stated so succinctly is the

truth. No amount of propaganda can

change that sad reality. One particularly

annoying aspect is that its seems that the Turkish government grudgingly at

best admits that many lives were lost, but on both sides. There was no

genocide. Does this not smack of what

amounts to a perverted plea bargaining

mentality?

A nephew recently drew our attention to a

‘Korpehtsi’ Old Armenia photograph that he saw posted on the Western Armenia Facebook

site.[3] When we examined the photograph, we

recognized it and even suspected where it came from and indeed its origin, but

felt that the photograph certainly deserved a more detailed and accurate commentary. In fact, as will become clear below, one of

us (ADK) was intimately connected with its preservation.

Perhaps the proverbial “silver lining” will turn out to be that

the Facebook posting has prompted us to undertake the task of elaborating on

the photograph. It was certainly not a

major priority since it has always been seen as a family matter. But now attempting to do justice to the photo,

we hope that we can show by example that individuals who profess

great interest in such matters will take it upon themselves to become a bit more

serious and engaged at a higher level - perhaps even be encouraged to take on

the chore of trying to learn something in the process. It may well be that collecting and performing

superficial siftings of sorts via surfing the Internet has its value. Intuitively this seems not, however, to be a

very helpful activity. Indeed, the old

time Armenian villagers, especially the older ones, many of them unlettered, especially

the women, and even the younger survivors who had their elementary schooling

interrupted by the horrendous Genocide period would urge, “Shidag, shidag ereh,”

that is to say, “Do it correctly!”[4]

In

short, we try here to demonstrate by means of this article how individuals or

families who might have access to Old Country photographs can try to elaborate

on them both for themselves and posterity.

But such an attempt at elaboration should be initiated and carried out

starting at a reasonable level of sophistication. It may be a slow process, but the outcome inevitably

will be a far more rewarding and valuable one.

By

so doing, you will have preserved memory and cultural heritage and thereby have

shown harkank or respect at an

appropriate level. Do what you can, but

please try to do it properly and honestly. If it is incomplete, say so, and perhaps

someone ‘out there’ can fill in the gaps.

There is a wonderful saying among the Armenians of that era that goes

something like this: “If you scratch the skin of an Armenian, a relative

through marriage will emerge!” [Hayots

mahrminuh guh kerress, khunamee geh ellah!][5] All well and good, but please

also recognize the simple fact that one has to set some sort of stage for

learning. Merely circulating photos, barely

examinable or even of much better quality, is not, we argue, enough. In a word, none of this exposition is meant

to be an invective or destructively negative criticism. We mean it to be heuristic.

When

Djemal Pasha’s book entitled in English translation Memories of a Turkish Statesman - 1913-1919 was published in 1922,

he started off his last chapter, entitled “The Armenian Question” with the

statement that “We Young Turks unquestionably prefer the Armenians, and

particularly the Armenian revolutionaries, to the Greeks and Bulgarians. They

are a finer and braver race than the two other nations, open and candid,

constant in their friendships, constant in their hatred” (Djemal Pasha, 1922

pg. 241 English language edition)[6].

Whether Djemal Pasha meant it or not

(for he was a very disingenuous man to say the least) it should perhaps be appreciated

that it is in this spirit of boldness and honesty that we take on the challenge

of bringing a broader context to this photograph.[7] And, while we deal with

this specific photograph, the approach is equally applicable in principle to

similar photographs, both those which are old and those which are considerably

more recent. It is a matter of

preserving one’s heritage and keeping alive whatever remaining legacy there may

be.

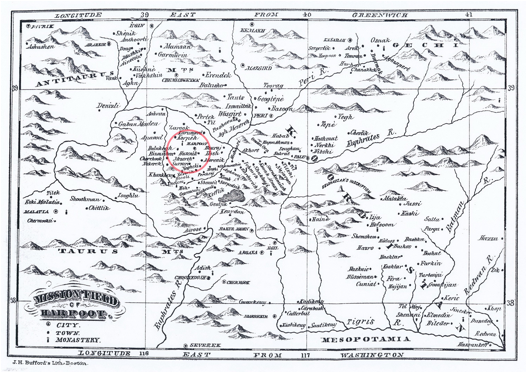

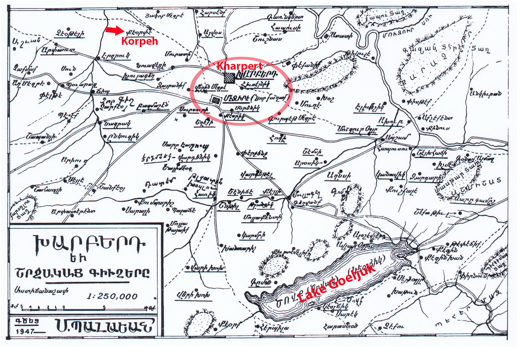

But before we get into the substance of this article, we shall make an effort to locate Korpeh[8] for the reader using a few old maps. Considerably more detailed maps, some more modern, are provided in the Appendix. Suffice it for now to say that Korpeh was a purely Armenian village in Kharpert province or Vilayet.[9] There were no Turks or other Muslims living in the village; neither were there any Protestants or Catholics.

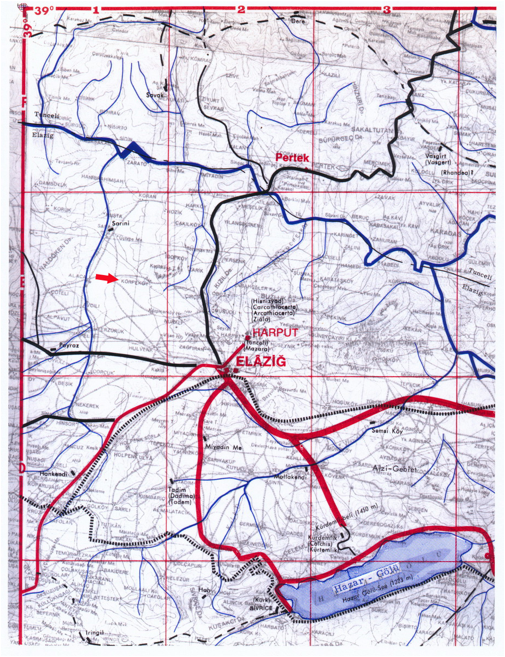

The

first map provided immediately below outlines in a very broad perspective, the

immediate area of Kharpert (it is spelled Kharput on this map). The drawing derives from just after the end

of WW I, and was made around 1919 when matters concerning boundaries and/or

spheres of influence or areas of the onset of Turkish nationalism had not been

resolved. Everything was really in a

state of absolute turmoil. The Kharpert

area has been marked with a red arrow and one can readily understand why some today

prefer to refer to the region as “Western Armenia” or “Western Historic

Armenia.”

The above map was first

published in Current History (NY) vol.

9 (1919) p. 415.

Kharpert (spelled

Kharput) has been marked with a red arrow to facilitate location.

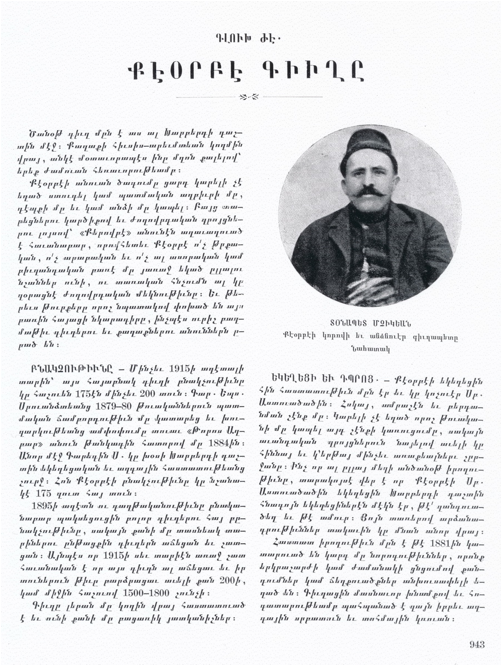

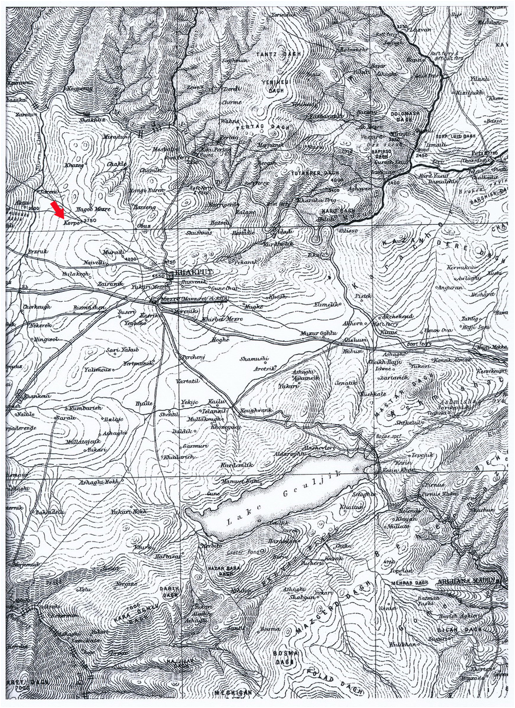

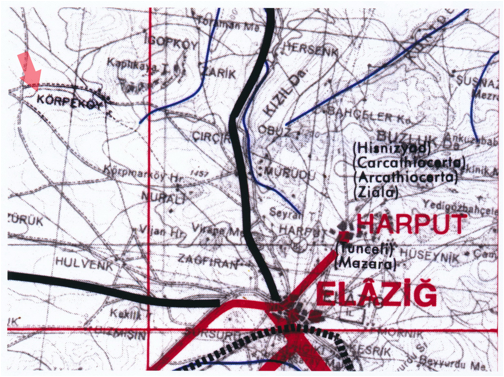

To

help further ‘zero in’ on Kharpert, especially on some of the villages of the

Kharpert plain, including Korpeh, which strictly speaking was not on the plain

but rather on a very hilly ‘mountainous’ area, we provide another map. It is a scan of a rather old one and dates

from 1868 (see Crosby Wheeler’s Letters

from Eden; or Reminiscences of missionary life in the East, Boston:

American Tract Society, following pg.118.)

Although the village locations are rough approximations, it is one of

the few maps that we know of that situates and locates clearly the various

major villages of the Kharpert region surrounding the twin small cities of

Kharpert/Mezireh. The names will be

recognizable to the descendants of those who came from or were connected with a

specific village. (We have added an Appendix

to this article which includes several additional maps that provide greater detail as well as some recent place

names in Turkish.[10])

Map of the

Mission Field of Harpoot Outlined by the American Board in Boston (ca. 1868)

Now

that we have a fair idea of the location of Korpeh, relative to the small

cities of Kharpert and its lower neighboring town Mezireh, we may return to

some of the specifics relating to the family photograph shown below.

Korpeh:

One of the Many Villages of Old Armenia Near Mezireh, Kharpert

The

villages were the heart of Old Armenia. And it was the villagers, easily described as the

“salt of the earth” as a result of their closeness to the land and their

traditions and values, who largely survived the Genocide, possibly as some have

posited, because they were tough and had become accustomed to hardships under

the Turkish yoke.

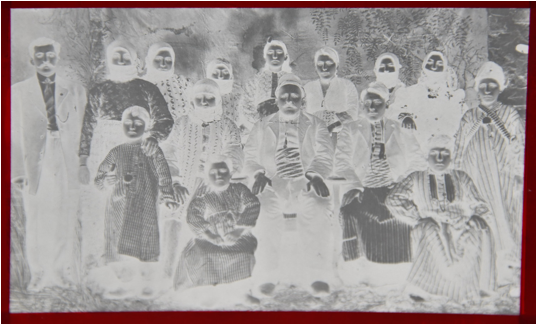

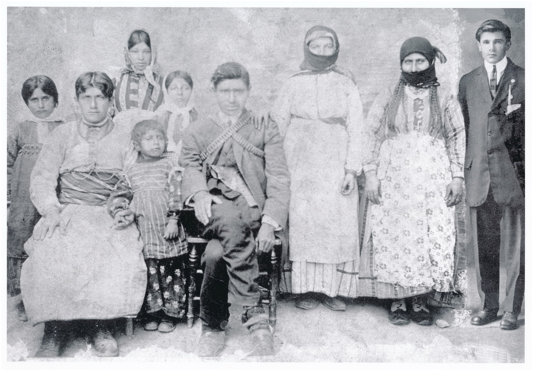

The

undated photograph shows seated in a central position Donabed Mechigian and

members of his patriarchal household a few years before the Genocide.[11]

Donabed was the Khoja-bashi or the Head-man, of Korpeh [see 12 for some details on the position of

Khoja-bashi.]

To

make a long and rather disturbing story moderately brief, only a few pictured here

in the photograph survived the Genocide. The one true Genocide survivor was Altoon[13] Mechigian DerKrikorian. She is standing, back row 2nd from

the right with an X marked above her

head. She survived the Genocide but a

young son named Kirkor [note the irk

spelling], not present in this photograph, died in a tragic drowning episode

early on during the exile ̶ often referred to in Armenian as the Aksor. The two others who did not experience the

Genocide were already in America and hence out of the reach of the Genocidists

(more below).

Altoon’s is a story that

we will go into here only very superficially but emphatically state that her

experiences, like those of so many other survivors, should be heard by would-be

Genocide-deniers or -revisionists before they open their mouths, or use their pens

or keyboards.[14]

Altoon’s

husband Bedros, the slightly older brother of Abraham [Aprahm] DerKrikorian, the

father of one of the writers of this commentary (ADK), had emigrated to America,

as had Abraham a few years later. Sarkis

Kazarian, the young fellow seated on a stool front row right, also went to

America before the Genocide (1912), so he escaped the massacres as well.[15] (Sarkis,

a first cousin to Altoon, had been orphaned early on and had been taken into Donabed’s

household. Sarkis later served in the

U.S. Army and was gassed at Verdun during WW I but survived. He died in 1960 in Worcester, Mass.) As already stated above, family Patriarch Donabed

Mechigian is seated in the center of the photograph. He seems portly, and sports a wide, colorful,

patterned waist band. We will not

comment here on his headgear which is a story unto itself.

As

was the usual modus operandi during

the early stages of the Genocide, the two grown men and one of the youths in

this photograph living in the extended household in Korpeh at the time (Donabed,

and his son Minas, standing at the left, and younger son Khoren, standing at

the right) were taken away and murdered, charte´tsihn

— i.e. they massacred them.) The

rest of the family members were ‘deported,’ and as was the usual case, most lost

their lives in the process. That

actually was the purpose of the nominal ‘deportations’ ̶

to get rid of the Armenians.

Back

row, left to right. Minas Mechigian

(pronounced Meen – ahss, more on him below), son of the Khoja-bashi

Donabed. The woman standing next to Minas is his wife Nazeli; the name of the

child on whose left shoulder she has her arm is Mik´hael. Next in the back row, standing, is Gul´tana [gul

meaning rose in Turkish, thereby something like Roseanne]. (Gultana is Altoon’s oldest sister. We do not know her married surname. She died on the road during the ruthless and

forced ‘expulsion’, and Altoon was with her when she expired.) The

next, shorter, veiled woman, is Khatchkhatoun [Princess of the Cross] –

she is Altoon’s father’s younger sister, therefore she is Altoon’s Aunt. She is a widow. Then comes Tourvanda (affectionately known as

Touro - she is Altoon’s youngest sister and is as yet unmarried. Standing far right, back row is Yeghisapet

[shortened form -Yeghsa, Elizabeth].

Yeghsa has her arm on her seated husband Sarkis’ shoulder. (Sarkis is a nephew of Khoja-bashi Donabed; he

will soon go to America.) To the right

of Altoon, (on left in the photo) is a still-unidentified-as to name, unveiled

woman who is an Aunt to Altoon (more on veiling below). [ADK knew her name at one time but this has

somehow fallen through the cracks. The

sad fact is that she too did not survive.]

Front

row seated, the older woman more or less in front of Khatchkhatoun is Badaskhan

Mechigian [this Armenian name means ‘Response’- suggesting that a child was

sent as the result of prayer]. She is next

to her husband Donabed, i.e. to his right. (She is Donabed’s second wife. His first wife, named Kouvar [Jewel or Precious

Stone, sometimes rendered as Pearl], had died some years earlier. The boy seated on a stool and on whose

shoulder she has her left hand is Ohannes, a son from her first marriage.) Next, to the left of Donabed, also seated is Sarkis

Mechigian, a nephew to Donabed. He is just

a year or so older than his cousin Minas, Donabed’s eldest son, and will soon

go to America, eventually to settle in Selma in the San Joaquin Valley of

California. [He died of botulism poisoning from eating badly ‘canned’ ‘per-per’ (Portulaca olearacea var. sativa, a garden weed which parboiled makes

a nice addition to a salad, or even pickled as tourshi for use as an appetizer etc.) at a 1939 New Year’s family gathering. His age was given at time of death as 49. A cousin named Ohan [John] Mechigian (not in

the photo) ended up dying from botulism a day later.[16] The young lad with the

bandoliers is Khoren, one of Donabed’s sons from his first marriage. Not in the photograph is yet another son

Avedis. He was about a dozen years

younger than Altoon’s brother Minas. He

was never heard from after the Genocide and was presumed to be a victim of it

as well.

Let

us therefore now pick up on Minas Mechigian and try to provide a few additional

details. He is the fellow in western

dress standing at the far left. He is Altoon’s

oldest brother and had gone to the United States hoping to earn enough money to

enable him to bring his wife and son Mikhael to America. Unfortunately, that was not to happen. But, fortunately there ends up being some

sort of memorial to him in the form of the photograph under consideration,

because following a widespread custom, those men upon leaving the Erghirr [the Land] would, whenever

possible, take a family group photograph with them, and later have themselves

incorporated into the photograph. This

was done by having a professionally taken photograph inserted into the group ̶ usually at a margin ̶ and re-photographing the whole. Minas had come back to his village in Turkey from

America for a visit, but got caught up in the fury of the Genocide. He was murdered after being ‘arrested’ and ‘taken

away’ with his younger brothers as had happened with his father a very short

time earlier.

It

is perhaps worth commenting here that had Minas not taken the photograph to

America, and had he not left this copy in America, this family photograph with

him in the picture more than likely would not exist. Some years later the photograph was given to

Altoon by a friend with whom the photograph had been entrusted, when she finally

reached Worcester, Massachusetts, She

had survived the Genocide in all its horrors, including time in the Hama encampment

(for all practical purposes a concentration camp, or as some foreigners called

it a “refugee corral”) in the Vilayet of Suria [Syria], all the while

apprehensive for fear that they would be moved out to Der Zor to be killed. The name of the person who kept the family

photograph has unfortunately been lost. Perhaps

it will surface one day, but it was a fellow ‘keghatsi’ [pronounced as kegh-ah-tsee,

or fellow villager] who had emigrated to America earlier, prior to the Genocide.

To

give yet another dimension to this photograph from Korpeh, it would not exist

even today were it not for the actions of ADK, called “Apa” by Altoon. She was known to him as his “NaNa. (NaNa is pronounced with equal emphasis Na-Na.

Kooirig is what she was called by ADK’s mother - the affectionate

term for sister, more accurately in this case, sister-in-law).

As

an aside, but we feel an important aside, we venture to interject that there

must be very few photographs of families from which one or two family members survived

the Genocide, and who actually have photos that they brought directly from the

Old Country. We know of only one (that

of a brother-in-law’s mother) from another Kharpert village who survived the

death marches and massacres. She had

secreted a family photograph in her waistband sash or ghodhi [kodi]. Understandably, the medium-sized mounted

photograph looks like the ‘survivor’ it truly represents. Fortunately it has now been preserved, scars

and all, through high resolution scanning, and those in it have been identified.

We suspect that not many photographs from

the Old Country would fill the criterion of being an actual Genocide-survivor

photo.

Getting

back to the Korpeh Mechigants Household photograph, on one occasion, when home on

break from Cornell University, while visiting his “NaNa” ADK got into a

conversation about her experiences in the Old Country. He asked about existing photos from the Ergihrr [the Land] and she brought out

the family photograph under discussion. As

a doctoral student learning some advanced studio-type photography as part of

training for scientific observation, record-keeping, note-taking and

documentation, the importance of the photo was immediately recognized. ADK borrowed the photograph and copied it in

Ithaca with the help of one of the campus professional photographers, a friend,

who had access to a very high quality large format 4 X 5 inch negative camera.[17] Many glossy prints 8.5 X 11 inch were made, sent back to

Worcester and distributed by NaNa to family members. That was over 55 years ago. She died in Worcester in May 1974.

So

as to emphasize that this little aside is not the product of a failing memory or

presented for dramatic effect, below is a photograph of the negative, hand-held

by ADK and photographed by ELT a few days ago in the summer light of Long

Island as background. The red is tape that

was used back then for masking unwanted edges of photographs. Most of the red masking

has been cropped off in this Photoshop adjusted image.

Had

an original mounted print of the photograph brought to America not been copied,

it would have been truly lost. Inquiries

over the years have not turned up the original mounted photograph which was

copied by ADK. There surely is a lesson

in all this.[18]

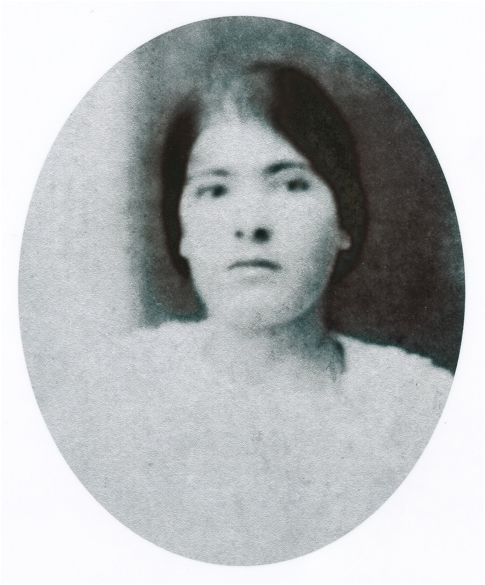

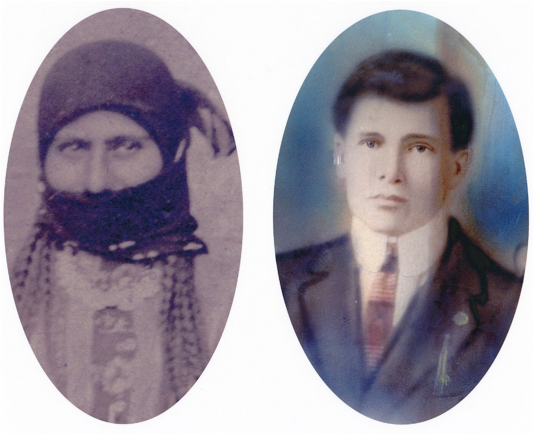

The composite above is a

photograph that was commissioned by Bedros DerKrikorian.

It

shows him in a western suit. Alongside

is his wife, Altoon Mechigian DerKrikorian [much later Simonian]. Her image will be recognized immediately as having

been copied from the picture derived from the one from Korpeh. It seems that Bedros [Peter] had access to an ‘original’

photograph in America, had her photographed from that, and inserted her alongside

himself in a large-size matte print. It could

be that Bedros had a photograph in America and so did Minas but he left it in

the care of someone back home when he traveled back to Korpeh. ADK only knows about one that came from

Altoon’s brother Minas via a third party.

The

copy of the photograph below shows an oval crop of Altoon Mechigian

DerKrikorian from a full-length photograph taken in Marseille, France just

before her emigration to America on the SS. Niagara in February 1921. One can see straightaway that she had shed

all appearances of a ‘veiled’ Oriental woman.

Some who have seen various photographs or published pictures of some married

Armenian village women from the Erghirr

may have wondered why any Armenian

woman, a Christian, should have had her face covered?

The

situation or practice among married Armenian village women in Kharpert at least

(so far as we know but probably elsewhere as well) was referred to as being in

a state of na-mahram (information

from ADK’s mother) and goes something like this. This elaborate linguistic breakdown derives

from information provided years ago by a language scholar and wonderful personal

friend and University teacher, now deceased. Apparently “mahram comes from the Arabic root

HRM meaning forbidden, but also “protected” thus applying for instance to the

holy site at Mekka, the Haram al-Sharif.

In the family, it applies to

intimates, usually the descendants of one’s parents and the parent’s siblings,

or one’s wife, or of one’s wife’s brother. These cannot be considered as prospective

marriage partners, so free social contact with them is permitted to a

woman. Na-mahram is the opposite: those

who can be considered as marriage partners, and with whom social contact must

therefor be circumspect. It can involve

various forms of avoidance, including veiling, but these are secondary.”

It

would be pure speculation on our part to say this practice was adopted largely as

a result of the extreme intensity of what might be termed acculturation of some

Armenian village peasants in some superficial aspects such as dress etc. within

the surrounding general and dominant Turkish Muslim environment. We say “Turkish” since married Kurdish women,

also Muslims, or Bedouin women did not cover their faces. Turkish women of the villages covered their

noses up to the bridge normally as well with the ‘no see-through yashmak’ [final k pronounced with guttural, thus –makh, again fide

ADK’s mother], whereas married Armenian women normally covered below the nose, that is mainly covering

the mouth.

One

aspect of using the yashmak may have

been purely self-protective. Muslim riff-raff

who might have been inclined to try to harass or molest an Armenian woman should

she happen to be alone might think twice if he saw that she was wearing a

veil. Or, he might have thought that she

was one of “them”; that is, Muslim and

thus off-limits. A more delicate

interpretation might be that the Armenians did not want to antagonize any

conservative Muslim element. All this is

pure speculation, of course, but none seems unreasonable.

But

there has always been a troubling aspect to all this from the perspective of some

of us who were in a position to ask about such matters but never knew enough to

do so. Or, who regrettably never thought

to pose more questions about veiling from those who immigrated from the

villages to America as Genocide survivors. For instance, was there any truth to the

assertion, admittedly read in later years in a few non-Armenian publications but

also supposedly in a few Armenian publications, that Korpeh village had accepted

Islam, if only more or less briefly, upon coercion during the Hamidian period,

and had reconverted to Christianity at first opportunity? The first and only opportunity to ask this sort

of ‘taboo’ question was when ADK asked his

Godmother Oghda Boghosian of Fowler, California. But she had been only 7 years old or so at

the time of the ‘deportations.’ When

asked the question, she was in her nineties but still very alert. Her

answer: “I never heard of it.” Be

that as it may, the fact remains that married Korpeh women covered their faces,

a few female names were decidedly purely Turkish, e.g. Gul´tana [ADK’s maternal

Great Grandmother’s first name], Altoon, rather than Voski- and even Sooltan,

sometimes used instead of Takouhi meaning Queen in Armenian. Even a few masculine first names were used like

Gul´khass (True Rose, nowadays taking form or encountered in family surnames like

Goolkhasian etc.)

The

reality of that possibility of apostasy to Islam for self-preservation may well

never be known of course. But to round

out the picture a bit, the deeply engrained conduct or social behavior concept

of ‘Amot’ (shameful) was especially dominant

in the Old Country Armenian culture, and one would have been more than likely encouraged

in the direction of non-disclosure, or hiding such a shameful [amot] act, even if it had been known, or

certainly had it derived from an unverified rumor. But, one point that should be taken into

consideration is that two senior Armenian men from Korpeh who made it to

America before the Genocide and who were young lads at the time of the Hamidian

massacres [“charteroon aden´neruh” - the

time of the massacres] and who had fled and taken refuge in the remote hilly

area near the village during the worst of it, described to ADK how they hid [baivetsak] but never made mention of any

subsequent conversion, or anything close to it.

Again, truth be emphasized, few Korpehtsis in America were religious

zealots. It was difficult for many of

them to reconcile what happened during the massacres and Genocide with a loving

God. That does not mean they lost their

religion completely but it does mean that they ended up being the ardent realists,

cynics or perhaps even pessimists encountered when and after they came America.

To close on this sad aspect of village life

in Old Armenia ̶ what should really be described as a life of subjugation

under a dominant Muslim culture ̶

ADK never believed the reports of conversion when he first read of them. He had too many experiences in very close

proximity and close exposure to survivors, and never picked up a hint of

it. Unlike apparently some who never

spoke of their ‘deportation’ experiences, women survivors from Korpeh never

hesitated to tell it like it was.[19] Ordinarily this sort of issue might not even

be mentioned, but the fact is that non-trivial questions remain

unanswered. Perhaps some enterprising

scholars might chance upon this aspect of temporary conversion of some Kharpert

villages en masse during the Hamidian

period in the future and be able to fill in the gaps.

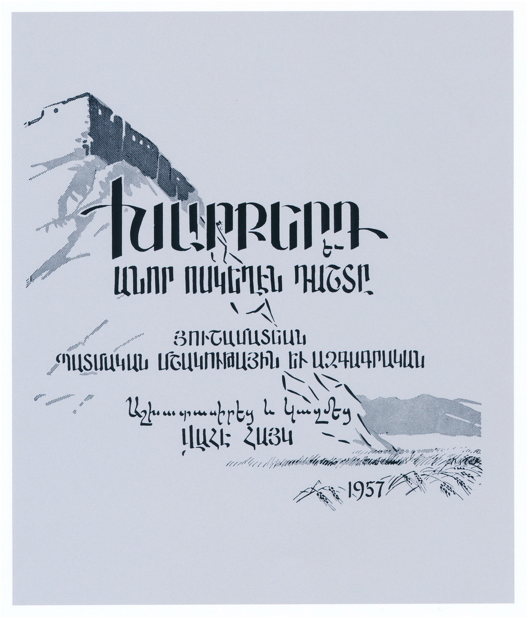

Korpeh in

the Armenian Compatriotic Union Literature

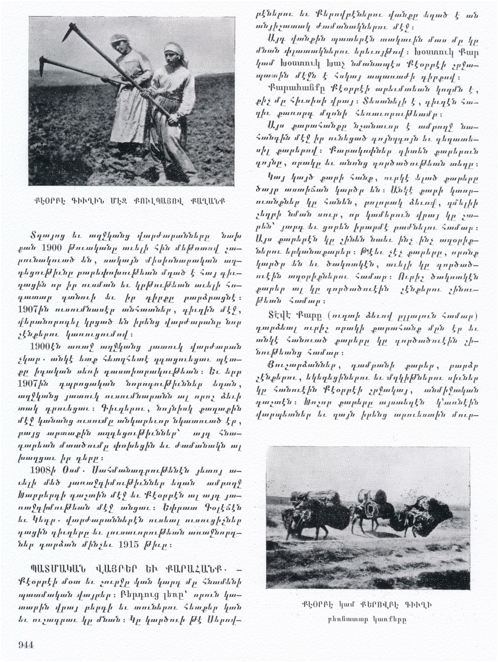

Below

we provide the title page in Armenian of one of the two large works dealing

with Kharpert on a grandiose scale. This

particular work, which we feel is the more complete and thus the more important

one, reads:- Kharbert ew anor

oskeghen dashte…

English title page given as Kharpert and

her Golden Plain, [Memorial] book of the history, culture, industry and

ethnology industry of the Armenians Therein.” The Armenian title page gives the date as

1957 whereas the English language one gives 1959. The later date reflects the

actual date of publication of this heavy volume.[20] Note at the page top the illustration reflecting

the ramparts of the Fortress or Pert, and the sheaves of wheat lower down

representing the Golden Plain and its prolific grain crops.

The

first map that follows below was taken from this Vahe Haig volume and shows the

surrounding villages. The second map

shows an enlargement of the same. These

two are in Armenian and can be studied by those who can read them. We have taken pains to add a few words in

English in red for non-readers. Note

Lake Göljuk (today Hazar Gölu) notorious as the location of some of the mass

murders, supposedly not of Kharpert people but mostly those from Erzerum etc.

The

pages of text etc. pertaining to Korpeh village presented after the Kharpert and her Golden Plain maps derive

from the Vahe Haig volume as well. It

will be of some interest to note that the oval photo of Khodja-bashi Donabed

Mechigian has been cropped from the Old Country family photo and inserted. No mention is made as to its source, or the

person(s) who made it available for publishing.

This would seem to strengthen the view that more than one photograph

exists, that is in addition to the one ADK and George Lavris copied.

No

effort has been made here to translate the original Armenian. (Ohr mi

as the oldsters used to say “Perhaps, one day!”) It is of some interest that the ‘chapter’

heading transliterates as Keorpeh

Kiughuh. The designation for ‘the village’

pronounced kiughuh is in so-called makur hayeren [proper (clean or

pristine) Armenian]. The Kharpert dialect

form would inevitably state kegh´uh. And therefrom, the term for a villager becomes kegh´atsi- not kiughatsi. The caption

beneath Donabed Mechigian’s photo and name states that he was the nahabed of Keorpeh. He was always referred to as the Khoja-bashi,

including by his daughter and other kegh´atsis

(ADK personal knowledge) and this fact should not be lost sight

of. Nahabed may well sound better in proper

Armenian but facts are facts. And

nuances do matter in establishing accurate identities of villages and the

inhabitants thereof.

We

shall save our comments on the other images selected for use in the Korpeh

entry of Vahe Haig’s book for another occasion.

The caption under the photograph on page 944 (lower right) is of particular

interest however since it not only gives the pronunciation/spelling as Keorpeh but adds “gam Keropeh” (“or Keropeh”).

Good examples of the fluidity

mentioned.

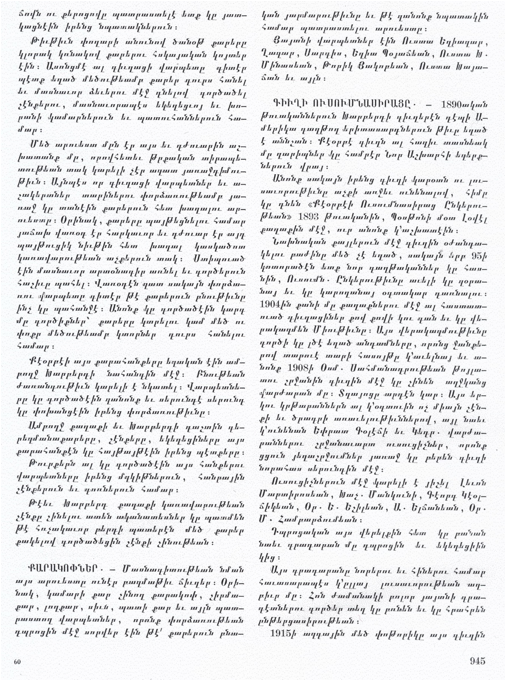

The Story of Keorpeh Village by Harootune

Shabouian

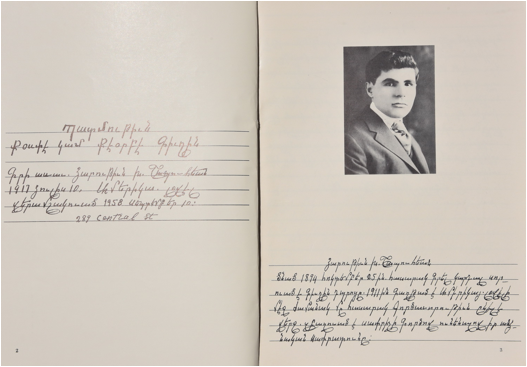

We

must now draw the reader’s attention to a seminal work on Keropeh written by Harootune

Shabouian (1894-1973) of Korpeh and Lowell, Massachusetts. It was not formally published but was hand written

and eventually printed by off-set. The 192

page long work was finished in the late 1950s but had been started a lot

earlier of course. Mr. Shabouian was a

barber and this work was clearly done as a labor of love. An especially useful part of this very

interesting softbound, illustrated volume is that it includes what we refer to

as a numerical “Household Listing” with arbitrary House Number and Family name,

first name of the head of the household, the first names of those in the

household, estimated ages and annotations such as emigration to America, or

wherever, whether a person survived the Genocide or, whether as a few did ‘turned

Turk.’ Such an accounting of a village

population is very unusual, perhaps even unique.[21]

A couple of pages from the book, one of which includes

a photograph of the author as a young man, are provided below.

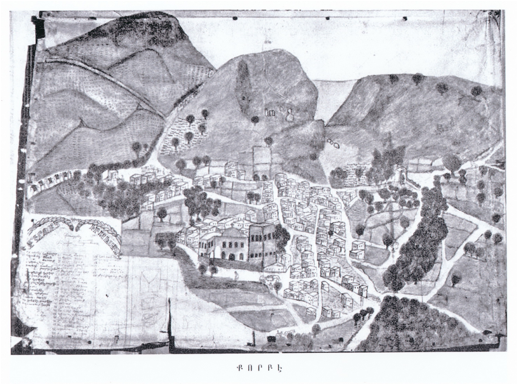

Among

the several quite interesting photographs included in the Shabouian volume are

a few drawings of the village. We were

told that the black and whites used, had originally been drawn in color but the

whereabouts of the colored ‘originals’ are not known. (They were apparently never in Harootune

Shabouian’s possession). Another

interesting feature of the Shabouian book village drawing(s) is that it is

entitled with the village name in Armenian as Keropeh, thereby retaining the original Armenian form. The photo of the drawing we present below does

not, however, derive from the Shabouian volume.

Instead, we copied it from a better quality published photograph with a

more visible but still unreadable ‘key’ found in Manoog Djizmedjian’s book Kharpert and its Children pg. 94.[see

Endnote 9 for details on that book. Let it also be mentioned that the image in

its various forms has appeared elsewhere, e.g. the late Asdghig Avakian’s Stranger Among Friends, an Armenian Nurse from Lebanon tells her

story, Beirut 1960 pg. 33 and “Stranger”

No More, an Armenian Nurse from Lebanon tells her story, Antelias, Lebanon

1969 pg. 37. She was an infant survivor

who was told she was born in Korpeh.]

One

can see from the drawing that Keropeh was a mountainside village. [Refer to

Endnote 8 for precise details.] The village church seen in the lower center bore

the name Sourp Asdvadzadzin [Holy Mother of

God]. According to Harootune Shabouian,

the village schools, one for boys and one for girls, were next to the Church. In 1908 thanks to the financial assistance

provided by the Keorpeh Educational Union, founded by emigrants from the

village living in the USA, a new boy’s school was constructed, and the old one

was assigned to the educational needs of girls.

The caption simply says

“Korpeh” [not Keorpeh]

We

do not want to allocate a lot of additional space to saying much more about the

village here but attention might well be drawn with profit to a few other

relevant points. These will serve to underscore a few of the generalities already

stated with reference to the Khoja-bashi Mechigian’s family photograph.

Below we give a copy of

a photograph of a family from Korpeh. On

the right hand side is Garabed Sarkisian who emigrated to Lowell, Massachusetts

as a married man. (He arrived at Ellis

Island on November 11, 1912, age 20.) Again, Garabed has been added ex post facto to the photograph but it

is a poor job. He looks too small and

disproportionate to fit in well with the others. Next to him is his wife Serpouhi.[22]

She, like Altoon Mechigian DerKrikorian is in namahrem with a yashmak

or face covering. She wears a necklace

with many coins strung on it. They seem to be silver Mejidiehs rather than golds

or altuns since gold pieces were

usually much smaller.[23]

Her shoes are quite

stylish and typical. They have upturned

pointy tips. These are the well-known pabushes [pabuç] that were normally

worn. On the left hand side of the

photograph in the rear is Garabed’s younger sister Makrouhi. Her head is covered with a letchak (headscarf). When first examined by us it appeared that both

Garabed and Sirpouhie had been added to the photograph. Today, we do not believe that to be the case. (We will not go into detail on the others in

the photograph except to say that they all lost their lives in the Genocide.)

Below we see portions of

a work that remains today in the hands of the Sarkisian family. The original is a badly damaged and poorly

aged color painting of Garabed and his wife Serpouhie (and Garabed’s sister as

well although we have not included her here) that was clearly based on the

faces in the full family photograph above.

It was painted by somebody or other in either Worcester or Lowell. We scanned it for preservation purposes and ovals

were cropped out. Unfortunately, Diggin

Serpouhie (Mrs. Serpouhie) is half-missing, ‘chopped off’ as it were due to

disintegration of the paper, but it was repaired a bit by us using Photoshop. All this emphasizes that Garabed missed his

family very much and also had an aesthetic, artistic sense. Serpouhie entered

the United States at Ellis Island in the autumn of 1920. Garabed had not seen his wife for 8 years! He died in 1962; she in 1973.

Finally,

a word might be in order about some of those who were among the very first

victims of the Genocide at Korpeh. The

village priest, Der Boghos (Father

Paul) or Boghos Kahana [married priest] Bedrossian, is shown below left. This image was copied from a reproduced photograph

in Vahe Haig’s book pg. 611. On the

right is a photograph now in the hands of a relative descended from a son of

Der Boghos named Sahag. Sahag emigrated

to America before the Genocide. The framed

photograph derives from an ‘original’ or at least better print of the same

image that we find in Vahe Haig’s book.

Although there is a “hot spot” on the photograph on the right, it will

be appreciated that it is considerably clearer.

Harootune Shabouian gives his age as around 43 when he was taken away

and murdered. Thus, Khoja-bashi Donabed

and Der Boghos, that is the Village Headman and Village Priest, were the first to

be done away with (fide family).

On

that sad note we shall end this tale of Genocide and witness through family photographs.

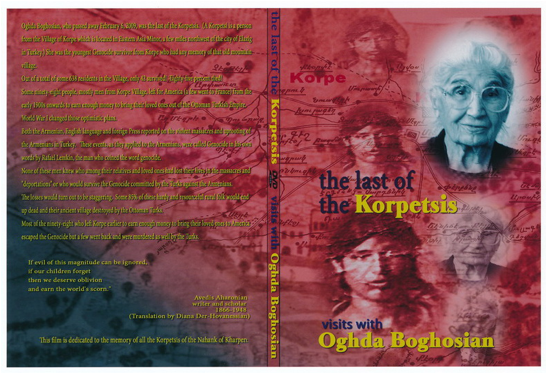

The

last of the Korpehtsis, that is the last person born in Korpeh, Kharpert was

Oghda Tuschonts Boghosian. Her exact age

was not absolutely certain but she was over 100 when she died in 2009 in

Fowler, California.[24] Her passing indeed signaled to all Korpetsi

descendants that one had come to the end of an era.

APPENDIX

The

following copy derives from a British Ministry of Defence map prepared around

1915.

Korpeh

(here spelled Korpe) is shown with a red arrow. Note that the notorious Lake Goeljuk or

Göljuk, today Hazar Gölu is spelled Geuljik.

The altitude lines give an idea as to how hilly the region was. Many missionaries and other Americans who had

been to Colorado in the old days said it generally reminded them of Colorado.

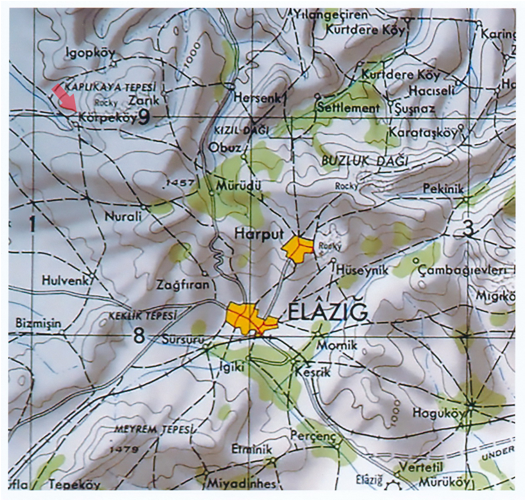

Below

is a road map published in 1998 that gives the modern name of Elȃzig [area

shown in yellow], instead of the former place name of Mezireh. (Elazig is

strictly speaking, not on the exact as old Mezireh. Harput [also in yellow] is a considerably

smaller place these days than the early upper Kharpert City that the Armenians

knew. Körpeköy (Korpeh village) is

indicated by a red arrow.

The

next two maps are from the Fr. Fritz’ Codex

Kultur-Atlas Türkiye, Türkei, Turkey Teil 9, 38/35-44 (1965-1966,

Codex-Verlag, Gundholzen - 1:300,000).

Körpeköy (Korpeh village) is indicated by a red arrow. Lake Göljuk re-named Hazar Gölu will be

readily located.

Acknowledgments

We

have quite a few people to thank for their help and encouragement over the

years. They are so many that we will not

mention them by name. Sadly, many have

now passed on. Others who are still

alive will know who they are. None of

this would have been possible without them. Our sincere and heartfelt thanks.

ENDNOTES

[1] Wright Morris (1981) The camera Eye.

Critical Inquiry vol. 8, no. 1 (Autumn)

pp. 1-14 p. 4.

[2] We will perhaps be forgiven for not being adherents

or admirers of the prevalent culture referred to in abbreviated form as “PC”

– “political correctness” or “politically correct.” Frankly, we tire of self-serving myths and

selective renderings of factoids by deniers of the Armenian Genocide.

[3]

The older Korpehtsis, the natives of Korpeh, knew, of course, that the original

name of their hilly village was Keropeh in Armenian, alluding to the cherubim

since it was a ‘mountainous’ village. (Incidentally the word korpe in Turkish is said to mean “the

littlest child.” (On that basis alone

one would reject any Turkish origin for Keropeh village’s name. It is curious though that efforts to erase

Armenian village names and to replace them with Turkish ones was overlooked by

those responsible in this effort. Our

conjecture is that this ‘oversight’ was not in fact an oversight but more

likely an unawareness of the full Armenian heritage of the village. It was in short not changed out of

ignorance.) In any case, survivors who

knew that Keropeh was the Armenian name, would inevitably refer to themselves

as Korpehtsis—articulated as Korr-peh-tsees (equal emphasis on all

syllables; therefore our preference for the transliteration as Korpeh, not

Korpe. Village names could be a bit

fluid according to the specific time-frame under discussion. As another example of this sort, some of the

villagers from Ashodavan referred to themselves as Ashodavantsis but most

referred to their village as Ahsh-vunn, thus becoming Ashvuntsis. The original village, spelled Aşvan more

recently in Turkish. as they once knew it has now long since become inundated

as part of the dam projects. Ashvuntsis

and Korpehtis were especially close friends in Worcester, Massachusetts.

[4] Back in February 2010 we were

stimulated to write an essay on a faked photograph that was causing some

consternation and clamor. Initially we

thought it was the usual Turkish genocide-denial tempest in a teapot. It was

indeed, but since we knew the photograph well, we felt it demanded an

explanation. We were told by a Greek

friend in England, born in Turkey, that the discussion essentially came to an

end after our Groong posting was circulated (see http://groong.usc.edu/orig/ak-20100222.html). It was entitled THE SAGA SURROUNDING A

FORGED PHOTOGRAPH FROM THE ERA OF THE ARMENIAN GENOCIDE DEMONIZING AND

VILIFYING A "CRUEL TURKISH OFFICIAL": A PART OF "THE REST

OF THE STORY." We

showed that the forged photograph was published at least as early as 1919 in a

book in Armenian printed in Cairo. A

publication trail back to its source was presented for the forged (‘faked’) reconstructed

image. We concluded that the `silver lining' in all this was that it would hopefully

stimulate work on the study of attestation and attribution of photographs

relevant to the Armenian Genocide and atrocities in the broadest context. Photographs and their captions ought to `say

exactly what they mean' and `mean what they say.' We wrote then, and repeat now that the

Armenian Genocide needs no validation by photographs but we owe it to those who

lost their lives and those who survived to do as good a job as possible.

[5] The Armenians, especially in the villages followed

the rule that noone should marry a person who was not at least 7 times removed

as to any potential relationship [so-called askagan

of yohtuh bodh.] It is an interesting point that peasants

seemed to have understood a fair amount about what we now call genetic

counseling? They seemed to be able to

figure out details of relatedness every bit as effectively as the computer

program “Family Tree Maker”! After the

genocide, when there were far fewer options open to survivors, some of the traditional

rules were broken on rare occasion but a priest that we knew admitted that if

there was any sin in performing marriages of individuals who might have been a

bit closer in relatedness than might otherwise have been sanctioned, then ‘Let

the sin be on me [merkh´uh unzi]!’ Back in 1980 Dr. Sarkis Karayan published an

article in The Armenian Review vol.

33, pgs. 89-96 entitled “Histories of the Armenian Communities in Turkey.” Somewhere along the line this listing was

placed on the Internet. We draw attention to this valuable paper again for it

is in such sources that this level of information about traditions and

practices will emerge now that the survivors who were sources of information

have now passed on.

[6] In the German original also

published in 1922 as Erinnerungen Eines

Türkischen Staatmannes von Ahmed Djemal Pascha, we can read on pg. 313 “Die

armenischen Frage” that “Wir Jungtürken sicherlich die Armenier und

insonderheit ihre Revolutionäre den Griechen und Bulgaren vor. Sie sind mutiger, tapferer, als die der

beiden anderen Nationen, ohne Flasch, zuverlässig in ihrer Freundschaft und

beharrlich im Hass.”

[7] In a review of Djemal’s book Memories by the distinguished political

scientist and historian Baron Sergei Alexandrovich Korff (1876-1924) we read:

“The last chapter of the book deals with the Armenian question and contains an

extremely weak apology for the misdeeds of the Turkish government. Djemal cannot deny the terrible massacres,

but his arguments of justification and explanation seem utterly inadequate;

they only help to prove how absolutely impossible the Turkish rule over

Christian and non-Mussulman minorities always was and always will be, whatever

party should come into power or whatever its intentions may be” (see American Historical Review vol. 28, no.

4 July 1923, pp. 748-750). For another

cool contemporary review see Bernadotte E. Schmitt in Political Science Quarterly vol. 38, no. 3, Sept. 1923 pp.

500-503. She says that “He insists that

he “had nothing to do with the deportations and Armenian massacres” and he

endeavored to assist the refugees.” It

is, understandably, beyond the intent of this essay to deal with Djemals

claims.

[8]

Spellings of Armenian place names as reflected in local pronunciations

vary. Keropeh was the usual Armenian

name. Keorpeh was also used by

Armenians. (We won’t go into how sounds and letters as consonant and vowel

shifts came to be switched according to local usage and dialects — just

think of those who used different pronunciations for bugh´lur versus bul´ghur for

parboiled cracked wheat). The Turks

referred to the village as Körpe and it

is still referred to as Körpeköy, or Körpe village. The “Korpehtsis” were,

first of all, “Kharpertsis.” That is,

they designated themselves as people who came from the Province of Kharpert. Kharpert Province was located in eastern Asia

Minor. (We prefer not to use the

designation ‘Anatolia’ as some have elected to do because use of the term

Anatolia, deriving from Greek meaning ‘the east,’ was originally restricted

geographically to the westernmost part of the Western Asiatic peninsula.) When spoken of in the context of the borders

of the old Ottoman Empire, Kharpert Province or Mamuret ul Aziz Vilayet as it

was referred to in English etc. [from the old style Eyalet, meaning Province or

State in Turkish] were changed several times for various purposes such as

facilitating better administration but also including such reasons like what we

now call ‘gerrymandering’– to the advantage of the Muslim population and

to the disadvantage of the Armenian Christian population. In late Ottoman times the Vilayet was known by

the Muslim name of “Mamuret ul Aziz” and

in fact, Elazig (pronounced EHL-lah-zuh), the name used nowadays for the ‘new’ ‘state’

capital is nothing more than an abbreviated form derived from the old name of

Mamuret- ul-Aziz — meaning in Turkish — Mehmet’s beloved — Mehmet

was one of the Ottoman Sultans; aziz means the ‘dear or beloved’. The town/small city of Mamuret ul Aziz was

known as Mezireh (or Mezre etc.) to the Armenians and more often than not,

referred to simply by close-by villagers as ‘Kaghakuh’—“the” City. Villagers hardly had cause to spend much time

in Kharpert city, whereas shopping and business matters were routinely done in

the lower town of Mezireh. After the

birth of the so-called Turkish Republic in 1923 the borders of the old

Vilayet/Province were changed again and Armenian town names were changed to

make them ‘sound’ “more Turkish.” As

recently as twenty-five years ago one could encounter spellings of Elazig as

Elaziz, Elazid, Elazýýð, Alaziz, Mamuret el-Aziz, Mamuret-ul-Aziz and

Mamurelulaziz but we venture to say that those are sure to have died out.

For

additional perspectives see the extensive Endnotes in our “Christmas

Celebration for Armenian Orphans in Mezreh (Kharpert) January 8, 1920: From

letters and photographs” dating from January 6, 2014 on Groong, Armenian News

Network http://www.groong.com/orig/ak-20140106.html

Again,

Elazig/Harput now represents but a small part of the old Kharpert region. Indeed, the name Kharpert is no more. We should also emphasize here that Kharpert

was used to designate not only the Province, but one of the two key ‘cities’ of

the Province. Kharpert

Khaghahk—meaning Kharpert City in Armenian; the other being Mezireh, in

Armenian. Kharpert or Harput was

situated on the top of a small mountain and was in name only the ‘official’

seat of the Ottoman Turkish Provincial Government. Mezireh was more the business center but it

was also the seat of the 11th Army Corps of the Ottoman Army. The Vali, or Governor-General of the Vilayet

also lived in the official residence or Konak in Mezireh/Mamuret-ul-Aziz. An English friend

working in Germany at the University of Cologne years ago and specialist in

Turkish anthropology communicated to me that today’s Körpeköy, i.e. today’s Körpeh

village, is in the extreme SW corner of what is now the Harput district,

placed, as so many Anatolian villages are, on the skirts of hills which rise to

its east. It is NW of Elazig on the road

between Şahinkaya (that is S with cedilla) and Üctepe (U with umlaut):

from Elazig one takes the Keban road, and it is the first road to the

right. The location is 38.46 degrees N. and

39.08, degrees E. (We have also seen the geo-positioning listed as

38°45´10´´and 39°7´55´´ DMS, degrees, minutes, seconds. A very large hydrological project (GAP) has

been realized in the region, and the largest dam is in fact the Keban Dam. This must have altered the whole subsistence

of the area. Körpeh is well away from

the water! In short, the Village still

exists.

[9] A word is in order about place name Kharpert or Harput, its pronunciation

and transliteration or romanized spelling, and although we are being a bit more

repetitious it matters little. We have

learned that it helps to put things in various ways and contexts. The spelling in Armenian of Kharpert begins

with the 13th letter of the alphabet Խ – pronounced khe

– խե.

The early American Protestant missionaries to

the region understood very well that Kharpert was pronounced by Armenians starting

with a guttural H, or ch as in Johann Sebastian Bach

(for Kh.)

How it was meant to be pronounced

in America and the west was stated in print more than once (e.g. Herman Norton

Barnum in The Missionary Herald vol. 72 January (1876) pg. 5. The choice to transliterate the place name by

English speakers into Harpoot ̶ Har- poot, with the H advisedly guttural rather than the equivalent Kh seems to have been quite deliberate

in view of the need for accurate pronunciation. But the fact was that many westerners subsequently

found it a challenge to make guttural sounds and Harpoot often simply ended up being pronounced with an ‘H’ – just

like it was spelled, as in the word house

which started with an aitch! The early reminders in print that it was to be

pronounced with the guttural seems to have been lost fairly early on. Harpoot is nearly always the spelling in

romanized transliteration of the Armenian Kharpert

in the old literature. Today, Harput is generally retained in the Turkish

spelling (and pronunciation). What took

place with the transliterated Turkish place name starting with H (originally pronounced as with

guttural Kh although spelled by

westerners with an H) also happened across the board and in many other cases. The much-touted reform edict of 1856

Hatt-i-Humayun was actually initially pronounced (and spelled by westerners) Khatt.

Germans usually spelled it Charput, the

French usually as Kharpouthe. The Danish missionaries usually used Harpoot (and

Mezre, rather than our preference for Mezireh).

For those who can read

western Armenian, the reference of choice is Vahe Haig’s [original Armenian name

Haig Dindjian]

Kharberd ew anor oskeghen dashte:

hushamatean azgayin, patmakan, mshakut̀ayin ew azgagrakan (New York: Kharpert Armenian Patriotic Union) 1959.

This big (1500

pgs. long) heavy, illustrated tome was "Prepared and published under the

auspices of the Kharpert Armenian Patriotic Union." (ADK recalls it had a

prepublication subscription price of around $45

a fairly hefty price at that time.)

Note the inconsistency of

cataloger’s Kharberd and the Patriotic Union’s Kharpert. ADK never heard Kharberd used by Kharpertsis. It seems that spelling should be relegated to academic

obscurity. All this reflects the weakness

of rules of transliteration that mercifully few follow. Some will know that an X now supposedly replaces kh. Another work that never achieved the

popularity of Vahe Haig’s book is that put out in 1955 by Manoog Djizmedjian entitled Kharpert yev ir Zavagnere [Kharpert and its Children], Fresno, 1955. It was 749 pages long and illustrated but

does not as does the Vahe Haig volume cover the 65 or so individual villages in

the Kharpert Plain. We cannot resist

drawing attention to the spelling of the author’s surname in WorldCat, an

authoritative device used by professional librarians for locating works in

participating libraries throughout the world.

There the spelling is Chizmechean,

Manuk G. Just who might think of

tracking down a volume under that spelling? So much for transliterations and Romanizing.

For English readers one should refer to Richard G. Hovannisian, ed. Armenian

Tsopk/Kharpert, (Costa Mesa, California: Mazda Publishers, 2002) for many details on Kharpert. For a general but good account of the events

at Kharpert/Harpoot during and immediately after the Hamidian massacres and the

relief work with orphans of that period etc. one can refer to William Ellsworth Strong's The Story

of the American Board; an Account of the First Hundred Years of the American

Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions (Boston: New York, The Pilgrim

Press; Boston, American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions, 1910)

− for a digitized version

go to https://archive.org/details/storyofamericanb1910stro. A more modern perspective on the range of

activities undertaken by the American missionaries is provided by Barbara J. Merguerian in her "Missions in Eden: Shaping an

Educational and Social Program for the Armenians of Eastern Turkey" in New Faith in Ancient Lands. Western Missions in the Middle East in the

Nineteenth and Early Twentieth Centuries, ed. Heleen Murre-van den Berg

(Leiden and Boston: Brill, 2007) pgs. 241-261. Reference should

also be made to Jonathan Conant Page's, Ringing the

Gotchnag : Two American Missionary Families in Turkey, 1855-1922 (Boston:

New England Historic Genealogical Society, 2009) for a very readable, yet scholarly account of the

long-serving missionary families of Wheeler and Allen and their work at

Harpoot.

Finally, although it may seem that we have

undertaken to write a dissertation on Kharpert, we would be remiss to not make

it clear that Kharpert, as the Armenians knew it is no more.

The province referred to as Kharpert is no more. The lower city of Mezireh, the provincial

capital is really no more. Years ago we

asked a linguist friend to dissect the name.

Here goes. “Ma´muret (with an

´ain or glottal stop: Arabic) means a prosperous and cultivated place, or 2.

(Simply) An inhabited place or town.

´Aziz (glottal stop again: Arabic) means dear or beloved, or 2. Even

sacred, holy (´aziz also meaning saint), or 3. Rare, highly esteemed. Although 3 is a learned usage, it seems most

likely to be the one appropriate here, with no. 3 as a secondary and

complimentary connotation. In short, Ma´muretul´aziz (with two dots over the u)

was the former term (now obsolete) for Elazig.”

The provincial boundaries are quite different now. It must also be remembered that the Vilayets

or provinces came into being in 1864.

Prior to that there were Pashaliks, for example the Pashalik of Harput!

[10]

Capabilities available today to locate things and places on maps by satellites

and the various tools of social media and the like have never been

greater. Few older researchers like us would

never have imaged things like the multi-faceted Falling Rain Global Gazeteer http://www.fallingrain.com/world/

or Google Earth https://www.google.com/earth/

etc. Not surprisingly, these aids

provides disadvantages as well as advantages.

There are numerous recent reports on disadvantages in connection with an

emerging “surveillance economy.” Some

of these are archived on The Intercept, https://firstlook.org/theintercept/

and also at https://firstlook.org/theintercept/2015/06/28/orwells-triumph-novels-tell-truth-surveillance/ What is most significant in all this

nominally innocent activity is that “We give our data to Google and Facebook

freely, in exchange for ever-better information; the hidden cost is that we

become complicit in our own surveillance.”

[11] It may be of some interest for

those interested in Armenian names, to note that family referred to itself at the time as ‘Mechigants.’ Mechigian per

se crept in somewhat later. Complications

engendered by seeming inconsistency in surnames to non-Armenians especially

among the villagers caused considerable problems for the foreign Consuls who

had to try to navigate in the areas populated by Armenians for three millennia.

The patronymic -ian ending [yan etc.] widely

associated nowadays with Armenian surnames became regularized at a

substantially later date - in America frequently only upon immigration.

[12] The position of Khoja-bashi was an

important one since he was the delegate of the Christian community at the local

ruling district council, which was controlled by Muslim overlords or Aghas.

If there had been a Protestant community, a so-called Vekil would hold an equivalent post as

well. In the case of Korpeh, where there

were neither Protestants, Catholics, or Turks (it was an entirely Armenian

village) it essentially meant that he was the main point of contact with

Turkish officialdom. The Khoja-bashi was

also responsible for seeing that taxes were paid in a timely and orderly

fashion and so on. (For many otherwise

hard to dig up and understand aspects of “Civic Administration” in Ottoman

Turkey at that time reference may be made to William Wheelock Peet pgs. 87-120

in Constantinople To-day, or the

pathfinder survey of Constantinople edited by Clarence Richard Johnson

(1922, Macmillan, New York.) Fortunately,

this important volume is available on the Internet https://archive.org/details/constantinopleto1922john)

[13] Her Armenian Christian name was

Voskitel [Golden Thread] but Altoon stuck. Altoon was the word for Gold in Turkish. Thus

the name would be akin to Goldie as in Goldie Hawn the actress, or Golda Meir,

the one-time Premier of Israel.

[14] One of the totally shameless

tactics employed by deniers and revisionists is that these histories which

Genocide-deniers often disrespectfully refer to as ‘Grandmother stories’ are,

according to them, to be discounted as hearsay and the like. They have no validity. The seemingly ever-growing long list of what

may legitimately be called “Deceitful Talking Points” have been conjured up by

some ‘bosses’ and the masses are expected to parrot these. After all, that is what an obedient,

uninformed mass of faithful deniers is expected to do. From our perspective, all that really matters

are

the stories by the survivors. On this

upside down scheme of things, the historians

now present and shore themselves up as the ‘expert witnesses,’ and the accounts

of actual witnesses and those who personally experienced the horrors are to be relegated

to the dust bins of anecdotal trivia at best.

Pure nonsense. Of course, it is

not politically correct apparently to point out that self-appointed experts,

pundits, politicians, or even ‘historians’ are too often self-serving, and have

made an industry of it all unto themselves. It is to the discredit of those who blindly swallow

this garbage. Example, when someone does

something to us that we do like, it is called “terrorism.” When we do the same or similar act, it is

said to be the “defense of democracy.”

[15] We cannot here go into the matter

of Armenian men preferring to leave the Ottoman Empire rather than stay and

suffer the consequences. This was especially

so when it seemed clear that universal conscription would be instituted

according to the second Constitutional regime. From what we know, it depended – some

did, but others simply ‘read the writing on the wall’ and decided to try to get

to America, even under the most difficult conditions. This even included cases of bribing under the

guise of feigning pilgrimage to Jerusalem for religious celebrations and as

pilgrims, only to again, by dint of bribery, further make one’s way from a port like Beirut on a ship going to Alexandria,

and then further outbound. These men

even had the traditional small tattoo memento [a Cross] near the base of their

thumb, between the forefinger. This

indicated that they had been hadjis,

a term used for both Muslims and Armenians (ADK, personal knowledge of a

relative through marriage.) Some

Armenian men did make it out of the Turkish Empire before the Genocide, earned

enough to try to get relatives out, but the outbreak of the War precluded

that. One in particular (ADK’s mother

paternal [and maternal] Uncle) lost their families in the Genocide. One took up drink and eventually drowned as a

result of too much drink. The other became a Gamavor or Volunteer in the French

Légion d’Orient, but never remarried. One of ADK’s father’s cousins was taken into

the Ottoman army. His is yet another

story. These personal details are

mentioned merely to show how various stories of experience and survival can be

elaborated upon ad infinitum.

[16]

The first to die of this botulism poisoning was Sarkis Mechigian on

January 3, 1939 (see Fresno Bee

January 4, 1939 pg.1. His age was given

as 48). His younger cousin Ohannes Mechigian,

age 40, died of botulism poisoning on January 4, Fresno Bee, again pg. 1.) Ohannes’ wife Margaret was also stricken but

she survived after she was administered serum rushed from UC Berkeley that did

not get there in time for the two cousins (Fresno

Bee January 9). The story of pickled

or bottled per-per (a green from Portulaca olerace used in salads etc.) as the source of the botulism

(circulated back East after their deaths) has not been verified by us. Another story going around was that the

home-made sausage (basturma?) may

have been the origin of the bacterium. Margaret

Mechigian, 1939 survivor of botulism

died in Selma at the age of 57 on July 1, 1962 (see Fresno Bee July 3, 1962.)

She left two daughters and a son, and a granddaughter. We thank Ms. Melissa Scroggins of the Heritage Center, Fresno County Public Library for her kind

help.

[17] George A. Lavris, of Greek

ancestry, helped ADK save this important photo.

[18] Ruth Thomasian, who founded Armenian Project Save back in 1975, has been a pioneer in trying to save the

photographic heritage of the Armenians in America. Sadly, all too often the identity of all the

individuals in photographs is missing or incomplete. Another lesson, label photographs when and

while you can and to the fullest extent you are able!

[19] One hears and knows of

“support groups” for this that and everything else these days. Those survivors from Korpeh, some 37 women,

an odd grown male or two who escaped from military service and made it back to

America through a ‘back door’ like Asiatic Russia, and a couple of male children

separated from parents and fellow villagers, out of the entire village of some

127 households and a population of some 700 or so sought support and

consolation by talking about it with those had experienced similar or nearly exactly

the same thing. One young boy, a little cousin

to ADK’s mother, was encountered by her in an Aleppo orphanage, came to America

and ended up in a state mental hospital.

Another young lad survivor, ended up in Beirut unbeknownst to most

Korpetsis. One of his sons showed up

quite a few years later in America announcing his Korpehtsi connections! One can do the arithmetic and see that most of

the villagers – more than 80% ̶ lost their lives in the Genocide.

[20] Actually catalogued in World Cat as Kharberd ew anor

oskeghen dashte : hushamatean azgayin, patmakan, mshakut‘‘ayin ew azgagrakan /

Ashkhatasirets‘‘ ew kazmets‘‘ by Vahe Hayk. Niu

York: Kharpert Armenian Patriotic Union, 1959. Vahe Hayk. 1500 p. :

ill. (some col.) ; 28 cm. "Prepared and published under the auspices of

the Kharpert Armenian Patriotic Union."

[21]

Some years ago we reduced the information to searchable format spread

sheets that used columns to segregate specific information.

[22]

Garabed means the Forerunner, as

in John the Baptist. Very often, albeit

incorrectly, as was the case with Garabed Sarkisian, Garabed was made into Charles

in English. He died in November 1962. Serpouhie, means ‘holy’ woman [in

appearance; Angel[ica]” would be a very close equivalent in English. As it turns out, she was Sophie on her

Americanized death papers. She died in

April 1982.

[23] A

mejidie equaled 20 piastres (grush pronounced khurush) nominally, but

the actual number varied according to locality.

It was roughly about the size of an old-fashioned American silver dollar.

[24] Happily, we made a DVD of some of

our more recent visits with Gunkamayr [Godmother] Oghda and integrated them

into a broader picture for ‘family only’ private archives and viewing. It will perhaps not be very evident from the

photograph that we used on the DVD cover but some scars where tattoos inflicted

on her by her Turk ‘guardians’ were removed from her chin and corners of her

mouth by an Armenian physician in Adana, named Krikorian (no relative), may be

discerned on close examination. She was

a lovely lady, and the youngest of the survivors of Korpeh. The background

photos show what she looked like on her passport photo. She was about 12. Oghda immigrated into America with the

Simonians of Korpeh under the pretense that she was Yeghazar Simonian’s

daughter, a child from his first marriage, from which he became a widower. The Simonians are pictured on the Front cover

of The Armenians of Worcester by Simonian

granddaughter Pamela E. Apkarian-Russell (Arcadia Publishing, Charleston, S.C.,

2000). The photograph derives from a

so-called yard long photograph by Worcester photographer K.S. Melikian, a

native of Yegheki village, on the Kharpert Plain very near to the twin

cities. The photo was taken on 16 August

1931 at a gathering of Korpetsis and friends who were recovering after the

Genocide, building families, trying to regain some status in the New World etc.

On the back cover there is a partial

view of Altoon Mechigian DerKrikorian and three of her four children. The identification of the individuals in the

yard-long photo has also been one of our projects. Numbers in red were put on individuals for

identification, spread sheets circulated and as complete as possible identities,

names in Armenian and nicknames and relationships achieved or at least

attempted. All in all, the Korpehtsis

have fared perhaps better at a personal identity level in terms of preserving

their Old Armenia heritage than the people from many other villages. We have played a role in that and this makes

us feel better. We know our roots.

|

Redistribution of

Groong articles, such as this one, to any other media, including but not

limited to other mailing lists and Usenet bulletin boards, is strictly

prohibited without prior written consent from Groong's Administrator. |

| Home

| Administrative

| Introduction

| Armenian News

| World News

| Feedback

|