Special to Groong by Abraham D. Krikorian and Eugene L. Taylor, Long Island, NY

LONG ISLAND, NEW YORK

A recent release by Gomidas Institute, London sent to Groong Saturday 14 November 2009 entitled `Adana Massacres, 1909 Focus of Istanbul Workshop' captured our attention; especially since the first paper presented was reported by Roland Mnatsakanyan as `an unusual one ... a discussion of Turks who saved Armenians in 1909. The fact that Armenian[s] were massacred was a given, and the speaker presented a sensitive examination of righteous Turkish officials who saved potential victims. The speaker used Ottoman records to show how Ottoman Armenians petitioned the state to recognize one such Turkish official for his role in saving an entire community. This first paper took some of the sting out of the workshop, where the audience could sympathise with the Armenian victims of 1909 without vilifying `Muslims' or `Turks' as single categories.

Our first reaction on reading that was `How fragile the goodness of humans can be!' Only six short years after the Adana/Cilician massacres, the ultimate destruction of the Armenians of Ottoman Turkey was under way. During the years of the Armenian genocide many individual acts of altruism by Turks, Kurds, Arabs, both Christian and Moslem, and Greeks (before they themselves were violently subjected to genocide) took place and are well known. Many survivors had tales to tell of some kindness or other. But it should not be overlooked that no large scale massacres (estimated at some 20 to 30 thousand in Cilicia in 1909), and certainly no genocide can occur (estimated at least as a million in 1915-17), without the overwhelming complicity, if nothing else, of much of the populace. Little is known of altruism, be it `shaded' or not, from the Hamidian massacres period. Certainly nothing we are aware of, other than what we will report here, has been written about altruism during the Cilician massacres. Thus it will be good to learn of more specific examples, and the exact circumstances surrounding them, from the 1909 massacres. This is especially so since any survivors among those who experienced or witnessed the events have long since passed away.

We look forward to reading and studying the published versions of the papers presented at this `workshop' [complete with Questions, Answers and Comments we hope], as presumably will many others since the Adana and Cilician Massacres that were perpetrated in the spring of 1909 are certainly understudied despite the many lectures and commemorations made throughout this 100th anniversary year. (The adjective `understudied' is used advisedly since in many instances, even published materials for study are very difficult to access. For example, we have seen a detailed and very interesting report by Rev. Stephen van Rensselaer Trowbridge entitled `The Sack of Kessab.' It is a rare eye-witness account of what happened in that town of some eight thousand inhabitants situated on the `landward slope of Mt. Cassius (Arabic, Jebel Akra) ...upon the Mediterranean seacoast half-way between Alexandretta and Latakia.' World Cat, a global catalogue of books etc. that is used routinely by professional librarians everywhere to track down the whereabouts of copies, lists only one location. Hopefully there are other copies in various places available to would-be readers and will eventually work their way into World Cat, and thereby facilitate access.)

Most will agree that in order to understand the Armenian Genocide one has to have a good understanding of the Hamidian massacres of the 1890s and the 1909 Cilician massacres as antecedents of the final brutal resolution of the `Armenian Question' from 1915 onwards. Much too little has been written about the continuities and discontinuities of anti-Armenian persecutions and the widespread violence against Armenians in Ottoman Turkey before the Genocide. Certainly reports or findings based on `Ottoman records' are sure to be important for they will, or should (?) give a perspective that is frequently unavailable to those many of us who cannot read Ottoman script even if we were to have free access.

Nevertheless, serious scholars everywhere are expected to examine archival records with great care and to seek always to ferret out diverse documents which complement each other, to fill in perceived or real gaps, or to at least provide a broader perspective. In a word, archival documents don't necessarily tell the `whole' story. It has been said that newspaper accounts should be viewed as `first drafts of history,' and arguably, the same may be said for non-exhaustive studies carried out in archives. To draw a bit of an analogy, it is like the proverbial blind man trying to describe the elephant based on touch but being limited to only a few parts of that massive animal!

Attention may be drawn here to a quotable tongue-in-cheek statement made in a book length review of a severely flawed work written by the late Stanford J. Shaw, Professor of Turkish History at UCLA entitled `History of the Ottoman Empire and Modern Turkey...' (Cambridge University Press, 1976). The review was by the internationally famous scholar and Byzantinist (one among several of his many other specialties) Speros Vryonis Jr. and although what he said is more than a quarter-century old (see Balkan Studies vol. 24 no. 1, 1983 pp. 163-286) it is still very much to the point.

First some background information to the quotation that we find so telling.

Professor Vryonis' fastidiously constructed, excruciatingly detailed and thorough critique of Shaw's book is scathing. Vryonis and a very few other experts, including a leading historian in Turkey, literally tore the book apart, virtually page by page, and chapter by chapter. Those several reviewers who did praise the volume, wrote brief, very general and sweeping reviews reminiscent of press releases. They were seemingly oblivious to, or ignorant of the many glaring shortcomings - ranging from gross errors in fact to faulty interpretations and undocumented pronouncements - drawn not from archival sources as claimed, but mainly from secondary sources - some incorrectly read at that. One example of a gross error concerns what went on during the siege and fall of Byzantine Constantinople in 1453 under Sultan Mehmed II, the Conqueror. This is surely an important event in world history. Shaw states `Once within the city the Ottomans advanced slowly and methodically, clearing the streets of the remaining defenders. While Islamic law would have justified a full sack and massacre of the city, in view of its resistance, Mehmet kept his troops under firm control, killing only those Byzantines who actively resisted and doing all he could to keep the city intact so that it could be the center of his world empire.'

Contemporary sources (Greek, Ottoman, and Italian) presented by Vryonis make it clear that, and we quote Professor Vryonis, `...Mehmed II actually gave the order for the sack;...the Ottoman forces finally broke rank, lost all discipline, abandoned their ships in the Golden Horn allowing some Greeks and Latins to escape by sea (the Turkish troops from the ships in some cases even abandoned their weapons so that they would be free to plunder), and looted for three days. The frenzy of looting was such that many Turks actually fell to killing each other over the loot itself; Mehmed repented his decision to allow the plundering of the city for at the end of the third day it was `devoid of man, beast and fowl', a wrecked ghost town.' see Balkan Studies vol. 24 no. 1, 1983 p. 216.

Having said all that by way of background and to provide context, we will now give at long last Vryonis' characteristically understated and measured comment on the nominally unimpeachable value of the primary sources supposedly used by Shaw, and by extension, we believe sincerely and take the liberty to suggest this phrase to all who use archival sources with the belief that they are the ultimate `word' on a given topic. Vryonis states, and we quote `the claims and pretensions of the author [Shaw] are clear, unequivocal; he is [supposedly] presenting the scholarly and lay worlds with an objective book which has a solid foundation in a scientific and original exploitation and evaluation of the primary sources. Further, it [supposedly] departs from the old historical prejudices of all authors who have written before him, authors who have written either enslaved to prejudice or unhealed by the miraculous waters of primary sources (emphasis ours) end quote. [We have taken the liberty of inserting `supposedly' in brackets to the text to emphasize that Professor Vryonis is essentially ridiculing the bombastic, fallacious boastings that accompanied the release of Shaw's work, or were actually in it!]

To repeat, and keeping Professor Vryonis' sarcastic but all too true admonition or pronouncement in mind, Ottoman archival documents do not necessarily provide the last word, nor are we suggesting that anyone at the Adana Massacre Workshop intimated that they do. Obviously we could not claim anything of the sort was said since we were not there. Our cautionary note and skepticism applies not only to Ottoman Archival Documents. Archival documents everywhere present their own problems and challenges. The mere cataloguing of the documents may sometimes politicize them. Be all of that as it may, we openly admit here that we find it difficult to ignore or downplay information that we have picked up in our readings on how various Ottoman archival materials have been used - both responsibly and irresponsibly. Scholars who are in a much better position than we are to comment on diverse government archives in Turkey have made it clear that it is not an easy task to `mine out' accurate facts and thereby use them to draw reliable interpretations (see for instance Taner Akcam's `Anatomy of a crime: the Turkish Historical Society's manipulation of archival documents' in Journal of Genocide Research 7, no.2, June 2005, pp. 255-277 and his `The Ottoman Documents and the Genocidal Policies of the Committee for Union and Progress (Ittihat ve Terakki) toward the Armenians in 1915' in Genocide Studies and Prevention 1, no. 2, Sept. 2006, pp. 127-148. For convenient access reference may be made to Akcam's `Anatomy of Genocide Denial: academics, politicians and the re-making of history' posted in Occasional Papers of the Center for Holocaust & Genocide Studies, University of Minnesota, 28 pages long, see http://www.chgs.umn.edu/Histories/occasional/Akcam_Anatomy_of_Denial.pdf.

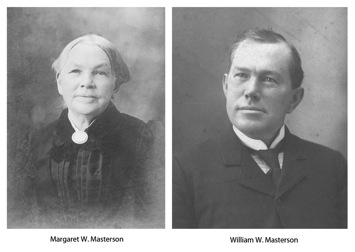

Therefore, in the spirit of what we have just said, we present here some preliminary `archival', i.e. unpublished, findings of our own that derive from studies on the penultimate United States Consul to Harput, Turkey-in-Asia, William Wesley Masterson.

In 2007 we sent a `special' to Groong reporting the death of the sole child, Mary C. Masterson, of William W. Masterson and his wife Louise Carroll Masterson. Mary was born in Mezere at the Annie Tracy Riggs Hospital on 23 June 1914. For a link to that posting see http://forum.hyeclub.com/showthread.php?t=14912.

As a result of our friendship with Mary, and with privileged access to private family materials in her possession, we have been encouraged to delve into her father's two-term tenure as United States Consul at Harput [Kharpert in Armenian, actually the American Consulate was located in the town of Mezere, the lower `twin city' of Harput]. Masterson, who was a trained lawyer, was appointed from Batoum, Russia to Harput 10 June 1908, and re-appointed there for another three-year term, then moved on to Durban, South Africa where he was appointed 24 April 1914, and ultimately posted to Plymouth, England. He had also served twice at Aden, Arabia. William W. Masterson died on 10 May 1922 in Plymouth, England of an infection that ensued after an appendicitis operation. Born on 9 February 1861, he was only 61 years old.

The first document we present is from RG 84 - Vol 13 pp. 419-421 at the United States National Archives in College Park, Maryland. It is one of many important documents that is much faded and very difficult to read without extraordinary effort. Our feeling is that we have `rescued' it from oblivion. It does not exist in microform. The report provides an excellent example of the many kinds of problems alluded to at the beginning of this paper and emphasizes how difficult it sometimes is to approach historical truth-even at so basic a level as being able to read an important document! Many archival records are not well preserved and their quality varies tremendously. The text of some type-written carbon copies is literally in the process of disappearing under one's very eyes. The single-page example we have selected to reproduce here represents one of the better pages in the Masterson report (see the reproduction of a photograph below). Scans or xeroxes are not allowed at the National Archives of pages in bound volumes, so one is somewhat limited in options.

A few words about the place Itchme will provide a geographical context. Some biographical information about the people will emphasize the nature of their involvement.

Consult http://fallingrain.com/world/TU/23/Icme.html for the exact location of Itchme. According to Vahe Haig [Haig Dinjian] in his `Kharpert yev anor Vosgeghen Tashduh', English title, `Kharpert and her Golden Plain', New York, 1959 p. 886), there were in Itchme before the Genocide between 250 to 300 Armenian households, and some 200 Turkish households. But these figures need to be corroborated since another Armenian source gives only 60 Armenian households, making no mention of Turkish hearths at all. The village's Armenian National Church was consecrated as Sourp Nigoghos, St. Nicholas. There were some Protestants at Itchme as well (see Masterson's report). The name of the village is said to derive from a Turkish word for mineral waters - albeit with the specific connotation of `don't drink the water cold.' The water flowing from Mount Mastar (2140 meters high) was apparently ice cold and thought to be bad for the health if drunk cold. No village history of Itchme exists so far as we are aware (see Sarkis Karayan in Armenian Review 33 no.1, 1980 pp. 89-96, http://www.armenews.com/IMG/pdf/Karayan_-_Bibliography_villages.pdf).

The Rev. George Perkins Knapp was the son of Rev. George Cushing Knapp, a missionary in Bitlis; Alzina Churchill Knapp was his mother. The two daughters of Rev. George P. Knapp spoken of were Margaret and Katherine, about 12 and 7 years old respectively. Rev. Knapp's demise occurred in Diarbekir 10 August 1915 after some 25 years of service in Turkey, first at Harpoot and then at Bitlis. Rev. Knapp was 46 years old at the time of the Itchme drama. He was fluent in the several languages of the region, which it is said, gave him an especially close touch with the people. The Knapp family left Turkey soon after the incident and arrived back in the United States on 23 July 1909. His wife and daughters stayed in the USA, nominally for the education of the girls, but he returned to Bitlis becoming the senior missionary there after the death of Miss Charlotte Ely in July 1915.

We have hesitated to name the Vali (Provincial Governor) of Mamouret ul Aziz referred to in the report. While Masterson's writings often mention the Vali - always in a favorable light - we have never encountered anything that gives his name. And knowing that Ottoman Valis were frequently moved around from place to place, and even post to post, we wish to establish without any doubt who is being referred to. This we have failed to do to our satisfaction so far. Ishak Sunguroglu who wrote `Harput Yollarinda' (meaning `On the Road to Harput') a 4 volume work in modern Turkish published between 1958 and 1968, by Yeni Matbaa, Istanbul [a facsimile reprint was issued in 1990 in Ankara by Elazig Kultur ve Tanitma Vakfi] lists several Valis but does not date them, so to say. Sunguroglu died in 1974 while preparing the 5th volume of this large, illustrated work. Unfortunately the illustrations and photographs, both in the original and reprint editions, are atrociously reproduced. Gertrude Bell, English archaeologist, traveler, writer, political analyst etc. - some even credit the establishment of the country of modern Iraq, at least in part, to her activities - has a fair amount to say about Harput in 1909. Like many English-speaking visitors to the region, she stayed at the American Consulate and we guess that she must have gotten an `earful' from Masterson. Her diary entry of 7 June 1909 makes interesting reading. The transcription of what she wrote is posted on line but needs verification and we are in the course of doing this (see http://www.gerty.ncl.ac.uk/diary_details.php?diary_id=800).

The second document is a letter written by Masterson to his mother back in Carrollton, Kentucky. His handwriting is not the easiest to read, and the stationery used in this instance is a sort of onion skin that allowed the writing to `leak' through (see the page below on the right.)

We will make no effort here to offer much commentary on what follows. We believe that the communications will speak for themselves, and as the saying goes, will allow one `to connect the dots.'

|

| April [faded, illegible], 1909 |

TO THE HONORABLE

JOHN G. A. LEISHMAN,

AMERICAN AMBASSADOR,

CONSTANTINOPLE.

S I R:

[The message starts off affirming and re-stating the

transmittal of two ciphered telegrams and acknowledging receipt of one

ciphered telegram dated 18 April from Leishman.]

Masterson goes on to report:-

`In addition to confirming these telegrams and acknowledging the

receipt of the one from the Embassy[,] I desire to submit the

following report concerning the political unrest in this district and

the threatened outbreak at Itchme.

It is the policy of the local government to minimize and make light of

this unrest among the people and attribute it all to uneasiness and

nervousness among the Armenians[,] and I will admit too[,] that the

Armenians are a nervous impulsive people possessed of but little if

any personal bravery, and I think too by their conduct on many

occasions, they are more than half to blame in all this friction

between the races, but it is folly for the Government officials to say

that these indications of an uprising among the Turks and Kurds during

the past week in the region of Itchme were all imaginary and that the

people were as usual pursuing their usual occupations.

In order to place the matter before you I will state the trouble as I

understand it. In the village of Itchme which is some six or eight

hours journey from here and in that surrounding country, the Turks and

Kurds are extremely fanatical and reactionary and there is no doubt

but what their hatred towards the Armenians is most intense, and

during the massacre years ago they reaped bloody vengeance among the

Christians by slaughtering them by the wholesale, and all along since

that time their treatment of the Armenians has been vindictive and

cruel, while the Armenians in their turn have done but little to allay

this feeling against them.

I think it is a fact that any outsider will observe, that since the

inauguration of the new regime, affairs in this interior country are

more disturbed than formerly. The Armenians, in their enthusiasm and

zeal in getting their rights under the new Constitution, have rendered

themselves particularly offensive towards the people who have

heretofore been accustomed to rule over and oppress them, and the

Turks on their side have undoubtedly, in order to intimidate the

Armenians and keep them down, talked massacre and bloodshed, and all

over this country there is friction and unrest to an unusual extent[,]

and in Itchme and nearby villages this trouble has become acute.

On Monday night, April 12, the Armenians at Itchme added fuel to the

flames by giving an Armenian historical play into which they added

local and up-to-date coloring, that brought matters to a crisis[,] for

all during the past week the Turks and Kurds in the surrounding

villages have been concentrating on Itchme all armed[,] and on last

Thursday and Friday there were about one hundred of them quartered in

a Mosk [Mosque] at that place[,] and in a nearby village there were

stationed several hundred all waiting for some thing. The Armenians

becoming in a panic, as usual on such occasions, ran away the

strongest of them, leaving all their belongings and the weakest ones

behind, scores of them even running into this place. And to

illustrate how bad the panic was[,] it is related that the Armenian

priest of Itchme died on Thursday night and Friday morning the priests

of the surrounding villages met to hold the funeral and they became

frightened along with the balance and ran off leaving the corpse in

the church, one of the priests, the strongest, running into this place

for protection.

Right here it will be well to state, that during the Easter holidays

of two weeks it has been customary for the missionaries of this place

to go to the surrounding villages in these plains to visit and hold

meetings among the Armenians, and at this time there were two lady

missionaries in a village near Itchme[,] and the two daughters of

Rev. Geo. P. Knapp were spending the holidays visiting some school

friends in Itchme[,] and it was particularly on account of the exposed

condition of these people that I took such decided steps in the

matter. Upon ?? [faded, illegible] Friday when the refugees commenced

arriving here and reporting to the Vali the condition and likelihood

of a massacre and of the arming of the Turks and Kurds, he sent a

company of four mounted police out to that place[,] they leaving here

at noon on Friday. That afternoon and evening[,] reports continuing

to come in of a disturbing nature, Mr. Knapp applied to me to assist

him in getting his people out of that country, and at about eight

o'clock in the evening I sent the Dragoman with Mr. Knapp to the Vali

requesting an escort for Mr. Knapp and that steps be at once taken to

preserve peace and save the threatened lives of the people. The Vali

at once provided Mr. Knapp with an armed mounted escort of sixteen men

under a captain and I sent along one of my Cavases [a sort of servant

and personal bodyguard associated with foreign Consulates and

Embassies] as an additional protection[,] and at nine o'clock at night

they started and then it was [that] I sent my first telegrams to you.

They arrived there at five o'clock on Saturday morning and their

coming seemed to have a most quieting effect. In fact from their

arrival everything at once subsided to normal conditions and for the

present no further trouble is looked for.

The interesting part of this whole matter is that two reports that

have been brought back by this little expedition, Mr. Knapp strongly

sustained the tale told by the refugee Armenians of the arriving of

the Turks and Kurds and of their being quartered in the Mosk [Mosque]

and nearby villages armed, seemingly ready for a signal for

something[,] and my Cavas, who is a Mahomedan [Mohammedan], even going

so far as to say that he had seen some of these armed men and that he

had talked to others who knew of these men being armed and waiting in

squads for some purpose, and as this Cavas has seen some fifteen years

service in the gendarmerie [this was Cavas Mohamed Onbashi, ADK and

ELT] I think by experience and training he would be in a position to

find out about such matters. While upon the other hand, the captain

of the mounted police reported that there was no trouble in the

community of Itchme, that the people were all quiet [,] that no

excitement prevailed[,] and that no outbreak was threatened and that

there were no armed bands of Turks and Kurds in that country.

In order to bear out the statements of the Armenians, Mr. Knapp and my

Cavas, there is a testimony unsolicited of a friendly Turkish Bey of

that village, who states that there was a band of Turks armed in the

Mosk [Mosque] on Friday and that night, and that on Saturday morning

early he came across a body of some two hundred Turks and Kurds

armed[,] secreted in a ravine near Itchme and that he stopped and

asked them what they were doing there[,] and advised them to quietly

disperse and return to their homes[,] and that if this massacre took

place this whole country would be ruined.

I am not an alarmist and heretofore have paid but little attention to

the excited stories continually being told by these nervous Armenians,

but I am strongly of the opinion in this case, that but for the timely

arrival of Mr. Knapp with that armed escort by daylight on Saturday

morning, that there would have been trouble and bloodshed later on

that morning, and a suspicious circumstance in this case is that the

armed body of four men dispatched by the Vali at noon on Friday did

not arrive at Itchme until noon on Saturday, 24 hours after starting,

too late to be of any assistance should they have been needed, while

our relief column went through in seven hours and in time to be of

service.

While the foregoing was being typed, I have received a letter from

Dr. [Herman Norton] Barnum which I shall embody as part of this

report. In this letter are suggestions that I hardly think should be

followed with indications no worse than they are, as I think the local

authorities are at least realizing the situation somewhat, but should

these disquieting rumors continue [,] I shall at once put the whole

question before you by telegram.

I have the honor to be,

Sir,

your obedient servant.

Signed [W. W. Masterson]

Consul

Enclosure:

Copy of letter of Dr. Barnum to this office.

[Rev. Herman Norton Barnum, D.D. was born in rural upstate New York near Auburn on December 5, 1826. He graduated from Amherst College, Class of 1852 and from Andover Theological Seminary in 1855. In July 1860 he married Mary E. Goodell, daughter of Rev. W. Goodell who served as a missionary in Constantinople for a good many years. In 1860 Rev. Barnum and his wife joined the Harpoot Station of the American Board, a station that had been permanently occupied since 1860. The Barnums were one of the same three families (along with the Wheeler and Allen families) who continued to serve exclusively in Harpoot until 1896. When Rev. Barnum transmitted the letter given below, we see reflected in it the diplomacy, wisdom and prudence of the senior American missionary at Harpoot. Their daughter Emma M. Barnum especially had been quite good about writing people back home in America what had happened during the Hamidian massacres--a time when a number of the mission buildings were burned. One of the infamous statements that she wrote back home was that `The Turks plainly said that: `There may be an Armenia, some day, but let us see whether there will be any Armenians left to live in it!' In short, the Barnums knew all too well the worst that could happen.

Rev. Barnum died in Harpoot 19 May 1910; his wife Mary died nearly exactly 5 years later also in Harpoot. They had nine children, six of whom died in childhood. All were buried in Harpoot. We have wondered more than once about the disposition of their graves.]

Harpoot, April 21, 1909 Dear Mr. Masterson:Having read a piece of the `Official Correspondence' sent by the United States Consul along with an enclosure from the American senior missionary at Harpoot to the American Ambassador at Constantinople, it will be interesting to read a personal letter sent by `Will' Masterson to his mother, Margaret White Masterson (1826-1911) back in Carrollton, Kentucky.Since I saw you other day I have learned that the situation about us is pretty delicate, and there is a good deal of fear among the Christian population. I have just had a call from two of the leading merchants in the city. One of them was told last week by a Turkish friend that a massacre was being planned, and he said if it did come off there would be no safety for any Christian. No Turk could be trusted to protect a Christian. Two days later[,] the Turk told him that the danger, for the present, was past. Stepan Effendi, second Police Commissioner, an Armenian, has said that if you could be persuaded to telegraph to the Embassy and have an order sent to the local Government to be on the alert, and put down any attempt at any disorder, it would be of great value. (This, of course, is strictly confidential. Stepan Effendi is a good man). I don't know how it will strike you, or whether Mr. Leishman would feel warranted in doing what is proposed, but if what has been suggested could be done I am sure that it would be of great value, and I should suppose that the Ambassador might, as a matter of information, and unofficially perhaps, adopt some plan which would secure such an order. The Itchme Pastor told me in detail yesterday what had happened in that region. Several people from that village have come to Mezere, and I advised that they should try to see the Vali in his own house and explain the situation to him privately, for the Turks are using threats. These conditions remind me of the past. They are utterly paralyzing to business, and they destroy all peace of mind in the community, so if you can do something to restore confidence it will be rendering a public service of great value. After what the people have experienced in the past it is not surprising that they should be easily thrown into a panic. The presence of a Consul is one of the sources of comfort. If the weather had been pleasant I would have ridden down to talk with you instead of writing this. Faithfully yours, H. H. Barnum

|

[I Mezreh Wednesday morn May 5, [19]09 `Dear Mammy, I suppose you will all be wrought-up very much over the reports of massacres and insurrections from this country and imagine some thing terrible has happened to me. I am very glad to inform you that I am safe and all right and that so far there have been no out-breaks among the people of this district; although as you will have seen by the papers there have been terrible times in other parts of the country. Our Governor has proven himself a hero during these times and it is to him alone these poor Armenians owe their lives. It now turns out that on last Friday week an order came to the Governor from Constantinople sent by the former Sultan authorizing a massacre among the people. But the Governor never made this message public, but did his best to allay the fears of the people and on Monday came the order announcing a new Sultan since which time all danger is past. But during that Friday April 23, Saturday 24 and Sunday 25 and until Monday noon the suspense was terrible, shops were closed[,] streets were deserted and an outbreak was looked for at any time. I never felt uneasy about myself for I knew the Turks had nothing against me, but I get terribly uneasy for the Armenians and I encouraged them all I could and let it be known should a massacre be started that I would receive all at the Consulate who could get here. My house and yard would have held at least a thousand and I was going to shelter all who could come. I think now that all danger is past and we will get along quietly this summer. But I shall stick right here to this place for some time now[,] not even going to Harpoot for the night so that if anything comes up I will be on hand. I did want to go down to Diarbekir some two days journey from here this spring but I shall give up that idea for the present. Well during the past week we have jumped right into the middle of summer. I have been sleeping with a sheet only over me for several nights and my windows and doors are all wide open day and night except my front door on the street. I wish you could see my garden-the apricot and cherry trees are covered with fruit. I have planted the melon seed and set out some tomato plants. I don't think I will trouble Hallie [Consul Masterson's sister] again about ordering flower seed for me from America again, she was badly cheated this time, only six nasturtium seeds in that packet and they were badly crumbled and rotten and the petunia seed I could put in my eye without discomfort. Actually the whole thing was a steal. All the seed together would not plant an area as big as my writing desk. I hope she did not pay much for what she sent to me, for if quantity entered into the bargain there was not five cents worth as they must have been exceedingly fine... By a strange chance about half of our Consuls stationed in Turkey are in America on leave[,] and with the outbreak I know they have all been ordered back. The Consuls at Trebizond, Smyrna, Salonika and Jerusalem and Baghdad were all away just at the wrong time. I would have liked to have been away too but I could not bear to ask for leave during these unsettled times and even if I had leave I have not money enough to go anywhere far. It costs over fifty dollars going to the coast and after you get to the coast you are then just starting. I think it better to stick it out right here now that I am here[,] say for this year[,] and then get away on leave and get a transfer while I am at home. It is such a job going to the coast and back--a month's trip--that I don't feel inclined to go anywhere away until I am through with the place...'The rest of the letter has no relevance to the topic at hand here.

Masterson was more than a bit of what we would nowadays call an `imperialist.' Moreover, he seems sometimes in his letters not to be overly enamoured with the Armenians, but it is also fair to say that and he is more than a little erratic in his statements about them. He vacillates from being quite complimentary to rather derogatory. At one point he is appreciative and admiring of the work done by the Armenian faculty and students at the 'American College' (Euphrates College). (Euphrates College, referred to as `Yeprad Colej' in Armenian, was founded in 1876 by missionary Rev. Dr. Crosby Wheeler. By 1878 it was established as a corporation of Massachusetts but a name-change in 1888 from `Armenia' College to Euphrates College took place because of Turkish objections to the word `Armenia'). At another point Masterson feels quite free in denigrating the Armenian professors at Euphrates College for refusing to sign a letter of thanks to the Vali after what we call the `averted massacres covered in this paper. This would be tantamount to acquiescing to a note of thanks saying `Thank you for not massacring us!' Strange indeed. We choose not to speculate here on the motives that Consul Masterson may have had in fostering this scheme.

For us, all this shows the ambivalence of many foreigners and diplomats, including missionaries serving the `re-development' of the ancient eastern, nominally doctrinally-corrupted Christians in the region. One could arguably sum it is this way:-`See how we bring you education and western ways? See how we teach you to understand concepts of righteous thinking and human rights? However, if you should dare put any of those teachings into practice, that is a No No. We do not really mean for a moment that you should think independently, and thereby irritate your Turkish overlords!'

Even so, and overlooking the peculiarities that seem to be inherent in the thinking of those foreigners who served in the Ottoman Empire in particular, Masterson appears from his `Official' communications to have tried to be fair and honest in his assessments.

Consul Masterson did not like his posting at Batoum at all and was very glad to get out. He did not like Mezere much better, certainly not at the beginning of his tenure. He was alone, and did not like the cooking etc. After his marriage to Louise Carroll in the summer of 1913, and with her accompanying him back to Harput, he seems, understandably, to have settled down considerably. Mrs. Masterson made numerous claims in writing about being enchanted with the whole adventure of being an American Consul's wife in Turkey and elsewhere. Both he and Mrs. Masterson had great affection for Baron Garabed Bedrosian, the Armenian Cavas (of the three Consular Cavases, one was a Turk, another a Kurd, and one an Armenian), who hailed from Buzmuhshen (Pazmashen and other variant spellings). Indeed, all those who Garabed served came to love and respect him.

Masterson never hesitated to write or talk unequivocally about what had happened in Turkey. In one typewritten script entitled `Turkey-a past and a future' he wrote ` ...there are the Armenians and Greeks, who are, or were, the most energetic, intellectual, liberal elements in Turkey, the natural intermediaries between the other races and western civilization - `were' rather than `are', because the Ottoman Government has taken ruthless steps to eliminate just these two most valuable elements among its subjects (emphasis ours)...'

The Mastersons left Mezere in the summer of 1914 with their baby daughter Mary, first for Beirut and then out to Alexandria, Egypt and onwards. Masterson's consular replacement at Harput, Leslie A. Davis, left Mezere at the same time and traveled with them. Trusted Cavas Garabed Bedrosian shepherded them on the arduous journey southwards to Beirut. Consul Davis had been granted leave to go to America to see his seriously ailing father, and his not very well mother, and to fetch his wife Catharine whom he had been forced to send back to America for health reasons. (Catharine was pregnant and ended up losing a baby girl soon after birth back home.) Leslie Davis and Catharine Carman were married in St. Petersburg, Russia. Mrs. Davis had but briefly stayed in Batoum while her husband Leslie was serving his first Consular appointment.

Having gotten as far as Alexandria, Consul Davis upon contacting the State Department was ordered to return to his post at Harput due to the outbreak of World War I. He turned out to be the last U.S. Consul at Harput. Much of his story is well known through Susan K. Blair's edited version of his final report to the State Department and published as `The Slaughterhouse Province: An American Diplomat's Report on the Armenian Genocide, 1915-1917', (Caratzas, New Rochelle, NY, 1989).

-- Acknowledgements: First and foremost we thank the staff of the United States National Archives `II' at College Park, Maryland for their help and many kindnesses extended whenever we have worked there. Thanks also to the late Mary C. Masterson. She often pointed out jokingly that technically she qualified to be described as a Turk because of where she was born. Mary had visited Istanbul several times but had never gone back to her birthplace. Finally, we thank several friends and relatives for reading a draft of this communication, and offering helpful comments. The usual disclaimer holds, of course, that we alone are responsible for any errors or shortcomings.

|

Redistribution of Groong articles, such as this one, to any other

media, including but not limited to other mailing lists and Usenet

bulletin boards, is strictly prohibited without prior written

consent from Groong's Administrator. © Copyright 2009 Armenian News Network/Groong. All Rights Reserved. |

|---|